Die With Zero Summary: 12 Lessons on Time, Money, and Living Fully

Reading time: 9 minutes

What Die With Zero Teaches About Time, Wealth, and Fulfillment

This article offers a comprehensive Die With Zero summary, highlighting Bill Perkins’ personal finance philosophy. It includes 12 of its most impactful lessons on how to align your money with a fulfilling life. This is a book that has resonated broadly with readers across the personal finance space, with optimizers in the Financial Independence, retire early (FIRE) community, and with me personally.

What you’ll get in this summary

✔ The core idea in 30 seconds (Die With Zero in one paragraph)

✔ The 12 lessons in a skimmable list

✔ The deeper reasoning (time, health, money, memory dividends)

✔ Practical ideas: time buckets, giving early, reducing retirement fear

✔ Where the book is strongest—and where it’s vague

TL;DR — Die With Zero 🌿💰

🧠 Money is a tool for experiences and memories, not a score to maximize.

⏳ Time and health decline—so “later” spending often delivers less value.

🎁 Give earlier—when it can actually change someone’s life.

🗓️ Use time buckets to plan experiences before they expire.

⚖️ Don’t be reckless: secure the basics, but then spend intentionally.

12 lessons (quick overview) — deep dive begins below (examples + FIRE context).

Experiences > net worth

Time, health, money are your core currencies

“Memory dividends” compound like investments

Don’t die with unused wealth

Give earlier (to maximize impact)

“Die with zero” doesn’t mean reckless spending

Tools can reduce retirement fear (longevity + insurance)

Experiences are a better legacy than inheritance

Stop living on autopilot

Time-bucket your life

Plan when net worth should peak

Take asymmetric risks when young

Quick answer: Die With Zero argues you should stop optimizing for maximum wealth and instead optimize for maximum life fulfillment. You do this by spending on experiences when you have the health and energy to enjoy them, giving earlier to loved ones, and planning life’s experiences across “time buckets”.

Who this book is (and isn’t) for: If you’re struggling to cover the basics or to pay off high-interest debt, this book isn’t a first step for you. Die With Zero is mainly for people who are already on track to retire comfortably but who risk trading away their healthiest years for an even bigger pile of money.

Why Die With Zero Challenges the FIRE Mindset

For many in the FIRE community, this book is a wake-up call—sometimes an uncomfortable one. It challenges the idea that FIRE is about escaping work or maximizing wealth, and instead reframes it as a tool for designing a richer, more intentional life.

The stereotypical member of the FIRE community is an avid saver and money optimizer. During the years leading up to retirement, most would-be early retirees are very focused on getting the highest savings rate possible in order to retire decades before the norm. In contrast, when thinking about the years after quitting their job—when they need to start drawing down from their nest egg—the focus becomes on how to set the optimal safe withdrawal rate (SWR) that allows them to withdraw sustainably from their portfolio.

Underlining the quest for finding the “perfect” withdrawal strategy in retirement is a strong fear of running out of money during the later years of retirement. We all get it, right? Who wants to run out of money when they are in their mid-eighties due to poor planning when they were younger? Better to work a few years more to be on the safe side—the famous “one-more-year syndrome” If this was your thinking until now, then this book may make you see things differently. It certainly did for me.

Before reading it, I leaned toward an “optimize everything” FIRE mindset—maximize savings rate, minimize spending, and sprint to the early-retirement finish line. Die With Zero planted a seed in me which has ultimately led me to pursuing a more moderate approach: still disciplined, but more willing to spend intentionally on family time and experiences that won’t be as valuable (or even available) later on. The surprising part is that this shift didn’t weaken the FI plan—it has made the whole journey feel more sustainable.

To get across the main theme of the book, Bill Perkins likes to use as analogy the fable of the ant and the grasshopper. We are taught from an early age that the fun-loving grasshopper goes hungry by not focusing on the future and maximizing pleasure now. Instead, we are told to emulate the hard-working ant—who, thanks to the daily grind, is able to accumulates food and survive. Yes, but Perkins argues the ant got it all wrong, too: when is the hardworking ant supposed to enjoy life and thrive? Or is it life’s purpose only to survive winters?

Die With Zero teaches us that the most important question is not so much about how much to save (which it also is to some extent, of course), but rather when to spend it. The central theory behind Die With Zero is that we should stop trying to maximize wealth and instead optimize for life satisfaction by timing our spending to match our evolving health and energy. Maximizing wealth and optimizing for life satisfaction are not aligned with each other—you can’t aim to maximize both goals simultaneously.

According to Perkins, our business in life should be to focus on the maximization of experiences and memories—that’s all we are left with in the end. When we look back in old age to examine our life, we shouldn’t feel regret over missing out on key experiences life had to offer, but instead look back feeling proud and at ease with how we conducted our life. We tried to juice as much fulfilment as possible out of it, and now we are at peace. It’s very unlikely that we’ll look back wishing we had accumulated even more money or had worked longer hours to get there.

The path towards maximizing fulfillment and memorable experiences is aiming to reach the grave with as little net worth as possible—ideally zero. This will mean that we were successful in experiencing every possible opportunity life has to offer under our financial circumstances and constraints. It means we were able to minimize wasting our precious life energy by overworking more than necessary in careers that don’t make us happy. This is literally one of the most common regrets of the dying.

Below are 12 key Die With Zero lessons that can change how you approach money, time, and fulfillment.

If you’re on the FIRE path to early retirement, remember to also enjoy the journey. Photo by Galen Crout on Unsplash.

12 Lessons from Die With Zero on Time, Money, and Living Fully

1. Prioritize Life Experiences Over Net Worth

The true goal in life should not be to maximize net worth—it should be to maximize meaningful experiences while you’re alive. In an ideal world, we would go about our day-to-day converting our life energy into experiences directly. In the real world, though, we need to go about that inconvenient, intermediate step of accumulating money in order to have those experiences.

With this, Perkins reminds us in an effective way that money is simply a tool. Just as most of us wouldn't collect power drills or hammers for their own sake, we shouldn’t mindlessly collect money without a clear purpose either. A carpenter won’t go about his life accumulating thousands of hammers, but will chose the number of hammers needed to perform their desired function.

Similarly, reaching the end of your life with $5M in your retirement account means you’ve squandered your life energy in pursuit of excess savings. You could have retired much earlier from your job, while you were still young and healthy, and spent quality time with your friends, family, and on meaningful early retirement activities instead. Perkins believes that this is just as tragic as wasting your money on consumerism—trading your life energy at work for meaningless gadgets.

When we are young, we are full of dreams and creative plans for the future, and initially go to work as a means to fulfilling them. But then, sometime along the way, many of us get trapped in the money or status games, where we stop viewing money as a means to an end and end up viewing it as an end in itself. We unpack the psychology behind these status games in a separate article, and why they so rarely lead to lasting happiness.

Once we’ve been inside the hamster wheel long enough it will have atrophied our ability to think about experiences outside of work. It doesn’t mean those unique, fulfilling experiences are no longer out there, it just means we’ve forgotten where to look or have lost the courage to pursue them.

Perkins warns us that there is real danger in getting “stuck” in this hamster wheel after you’ve made enough. Once we start climbing the income ladder, it’s very easy to become distracted and stay in the game long past what’s needed, either because we are led by inertia functioning on autopilot or because we are playing some form of the status game—deep down trying to prove something or to impress others. Focus instead on reaching what is enough, and then pull the plug—don’t continue to overwork in a job you are not passionate about.

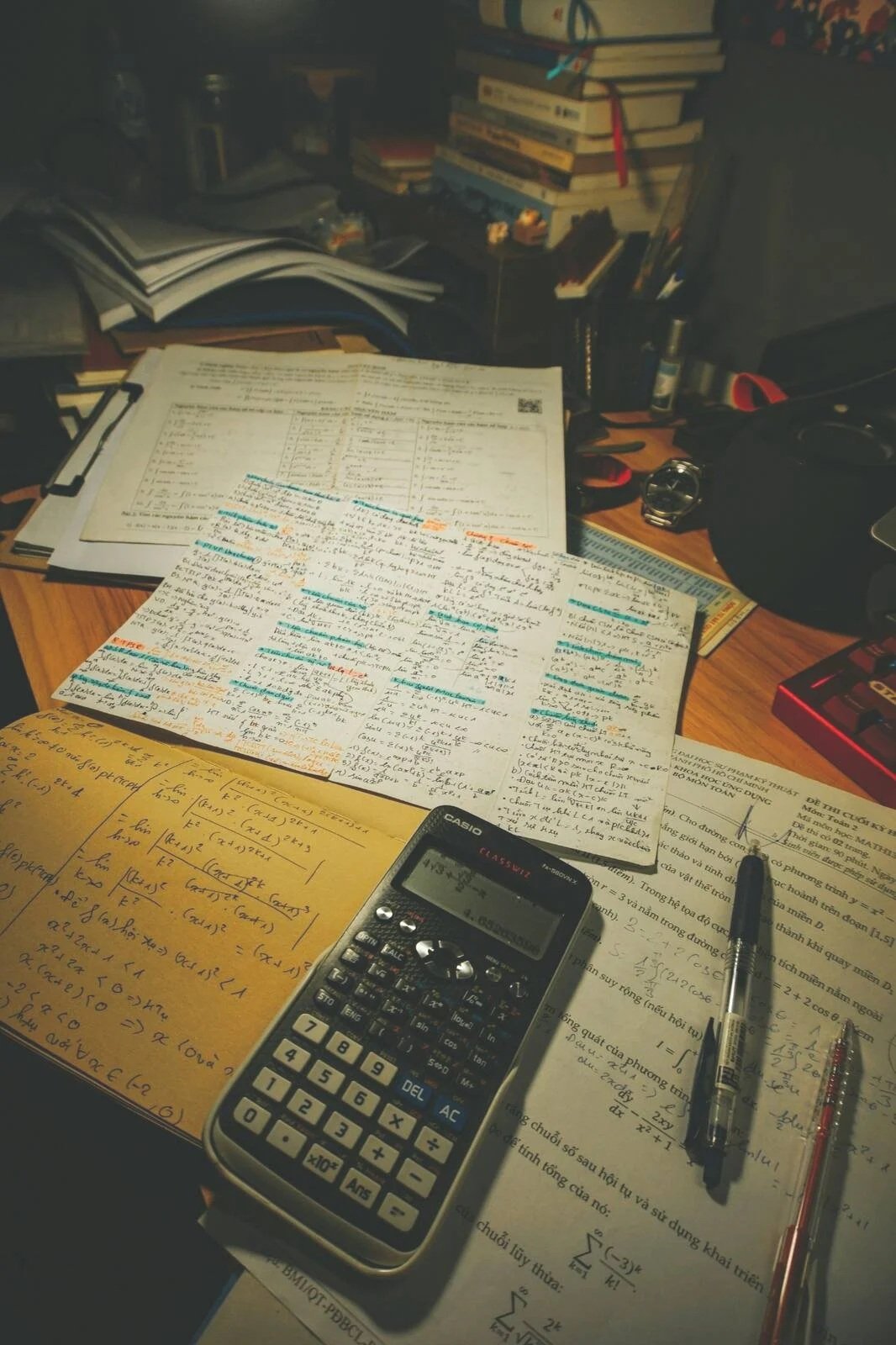

The timing of our life experiences matters greatly. Photo by Rachel Claire on Pexels.

2. Why Timing Your Life Experiences Matters

According to Perkins, time, money, and health are the three main currencies of life. It’s important to understand the interplay of these currencies and how they change throughout our life. When we are young, we have a lot of time and health, but not much money. This gradually changes as we reach middle age, where we now have money and may still enjoy good health, but unfortunately—due to different responsibilities—lack the precious time. Finally, in old age we typically recover time and have a lot of unspent money,* but no longer enjoy good health—a truth most people underestimate when planning for retirement.

Different life experiences have an optimal moment in our lives. The dynamic interplay of these three currencies means that not all experiences are enjoyed optimally across different age groups. If we agree that our life goal should be the maximization of net fulfillment—not to maximize our net worth at death—then we should focus on enjoying experiences at the right time. Think about dancing all night at a music festival or that month-long road trip in Europe with your friends. The freedom and spontaneity that define those youthful years simply don’t translate well across decades.

It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t travel in our 60s. It just means that we should be aware that—all else equal—the trip across Europe with your friends will be much more memorable when you are young. You will still enjoy certain activities in your 60s, but won’t have the health and energy to pursue many different experiences that have their optimal place at an earlier age.

The point here is that delaying gratification only makes sense up to a point—after that, it becomes a loss. FIRE-minded folk looking to retire in their 40s or 50s by delaying gratification too strongly may be missing out on important life experiences and fulfilling ways to spend their early retirement years, which ultimately become treasured memories and part of who they are. So, it’s important to keep in mind that some experiences simply expire and there is the risk of looking back with regret if you try to postpone them too much.

*It’s important to note here that the audience of this book is not for people struggling with earning money, but rather for people who are over-saving. The author makes this clear distinction early on in the book. This Die With Zero concept is certainly trying to solve a first-world problem.

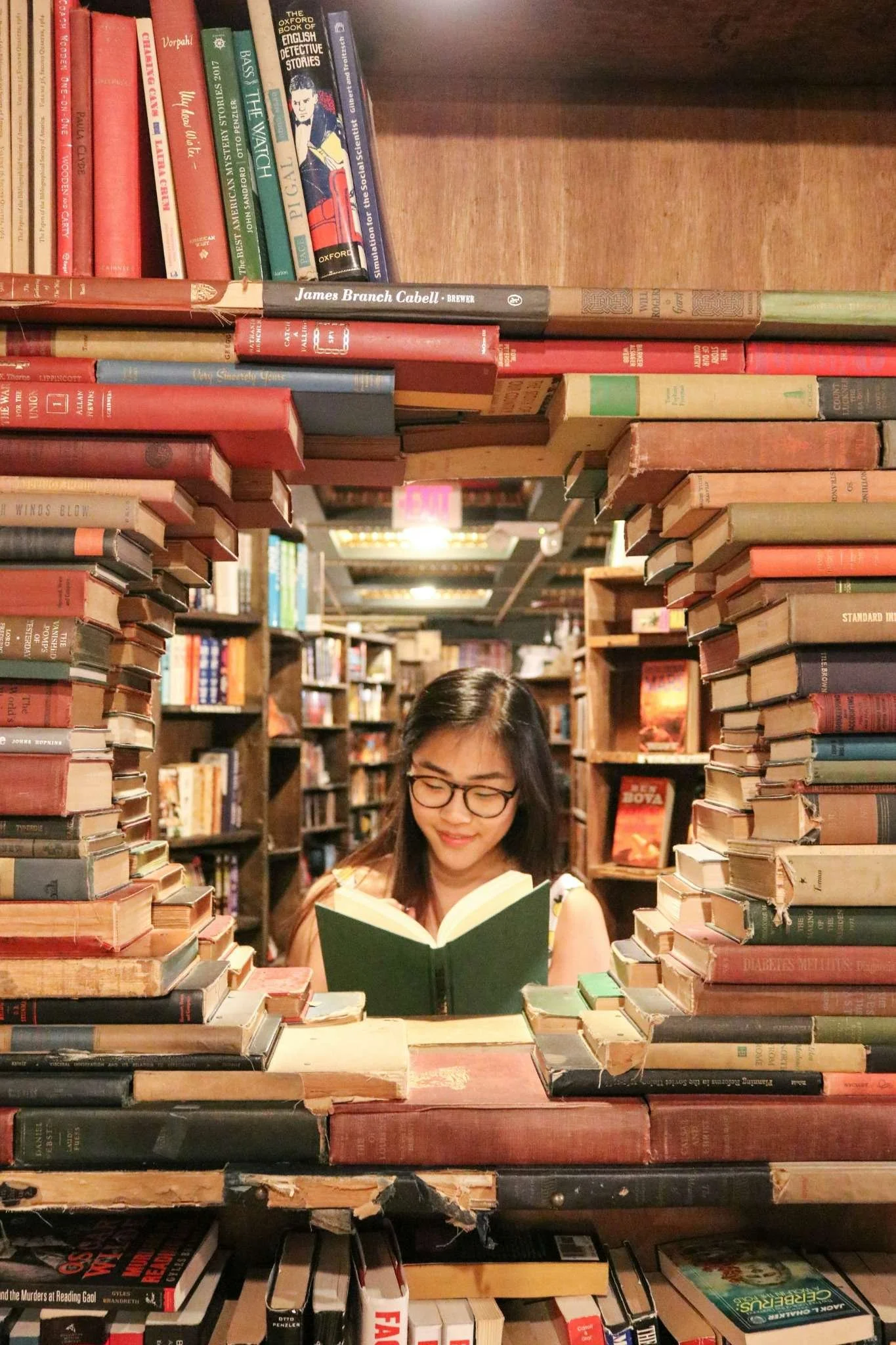

Life is the acquisition of memories. Photo by Jon Tyson on Unsplash.

3. Memory dividends or How Early Experiences Create Lasting Value

All else equal, we should try to enjoy the experiences earlier in life to maximize our “memory dividends”. In the same way that it’s important to start our investment journey early to allow for compounding to take place over time, it’s important to remember that we’ll benefit the most from experiences taking place sooner rather than later.

This not only has to do with the health component of being more physically capable of enjoying the experience that we mentioned earlier, but that we’ll enjoy the memories of those experiences for more years to come. That special trip with your kids or epic adventure with your friends will continue to deliver joy long after they’re over. You will tell the story at dinners, remember it fondly during rough weeks, and even use it as motivational fuel during challenging times.

These memories stack on top of each other in an analogous way that compounding returns of an investment portfolio do. The earlier an experience takes place, the longer we get to enjoy its memory. These moments become more than single events, they become part of who you are—they become your emotional capital. Invest in them early.

Many retirees continue increasing their net worth in retirement until the very day they pass. Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.

4. Avoid Dying With Too Much Unused Wealth

Perkins’ core critique of conventional retirement culture is that we’ve overcorrected from the grasshopper’s recklessness. As mentioned earlier, the ant was prudent, yes—but when does it get to enjoy life’s harvest? Perkins shows with data that retirees often die with unused savings, missing chances for joyful experiences.

Their financial net worth continues to climb even after retirement, while their physical ability to enjoy experiences steadily declines over time. Most of them wasted too many healthy years grinding away in a job that wasn’t fulfilling—a real tragedy.

It’s actually worse than that, since many people go into retirement thinking they’ll finally be able to experience everything they ever dreamed of. But, of course, when the time comes, they don’t. Now they are physically constrained by numerous health concerns or simply don’t have the energy that they used to. Travel may start feeling like a hassle—why go over there when you are perfectly content over here? In some cases, they may even feel guilty of spending down what they worked so hard to save. Whatever the case, instead of enjoying life to the fullest, statistics show that retirees continue hoarding money after leaving their job.

One criticism in Die With Zero is that dying with $2M means you misallocated your life energy. It means you traded your time—your life—for money you never used. In a very real, painful way, you wasted it. The goal of life isn’t to survive, but to thrive. But “what about the inheritance of my kids” I hear you ask? Let’s cover that argument next.

Who is the richest person of the cemetery? Photo by Mike Bird on Pexels.

5. The Case for Giving Money Before You Die

According to Perkins, traditional inheritance is flawed and most people end up giving too late. Often, kids receive their inheritance in their 50s, 60s, or later (one of my parents received their inheritance in their 70s). Of course, by this time it is usually much less needed. If the kids did well and planned for the future, then they are likely already on track for retirement, when not already retired. Any inheritance will be valued, but it’s impact will be far reduced than if they received it, say, in their 30s or 40s when they really needed it most.

Perkins refers to the “three Rs” of poor inheritance planning—giving random amounts, at a random time, to random people. You are leaving way to much for chance, and simply don’t know how much each person will ultimately get, when they will get it, or even if they will still be around to receive it. This is the least optimal way of sharing your wealth with people you love. In most cases, it just stems from not thinking it through enough—we are usually on what he calls “autopilot”, doing what others have done before us.

Instead, he recommends giving earlier to our loved ones, when it’s most needed. If you are trying to maximize the impact your wealth will provide your loved ones, then the ideal time to transfer wealth to them is not in their 50s to 70s, but in their late 20s to mid-30s. At this point, the “kids” are mature enough to handle the responsibility, but young enough that the money can meaningfully change their trajectory—help them buy a house, start a business, finance a dream trip, or simply reduce financial pressure.

It turns out that giving early not only maximizes impact, but it also provides substantial emotional benefits to the giver. You can see the joy and benefits of your action directly, and it also frees you up to spend the remaining money without any sense of guilt.

Photo by Tony Cowen on Pexels.

6. Planning to Die With Zero: What It Really Means

Implementing the Die With Zero approach doesn’t mean being reckless or messing up your finances during the later years. It means designing your life intentionally so you optimally allocate your time, energy, and money towards fulfilling experiences.

Each hour spent working once you’ve reached “enough” is time and life energy you can’t get back. It doesn’t mean you should quit your job—like I recently did—but it does mean being more intentional when asking yourself whether you are using your precious time wisely.

If you derive pleasure from your job and your work is meaningful—great, please continue! If you are amongst the lucky few who has found a job that provides meaning and fulfillment, there is, of course, no need to walk away from it. But even then, Perkins urges you to actually use the money you’re earning, rather than letting it pile up aimlessly.

In contrast, if you are part of the 79% of workers globally who don’t find fulfillment in their jobs, or simply value even more spending time with your family, friends, or other interests, then it’s important to identify when is enough and not to overwork beyond this point.

The Die With Zero plan requires a mindset shift—from hoarding wealth to thoughtfully spending it over your lifetime to maximize fulfillment.. The goal is not about how much you leave behind—we already saw that you should give much earlier to your loved ones or the causes you care about—but how well you lived your life.

People tend to over save out of fear of living too long. Photo by Scott Graham on Unsplash.

7. How to Reduce Retirement Fear With Financial Tools

A recurrent reason why people over save—and over work—is fear of living too long. Who knows what sort of medical care or other uncertainties they may face 30 or 40 years from now. Perkins doesn’t dismiss these concerns, but does call them solvable. These are not excuses we can make for over-saving, especially if you are aware of the solutions. Of course, the fear isn’t baseless—end-of-life and long-term care costs can vary dramatically depending on where you live.

In regards to the longevity risk—the risk of living too long and maybe running out of money—there are numerous longevity calculators available that can provide you with a plausible range of life expectancy based on lengthy questionnaires about your health, current lifestyle, family history, and more. I recently took a couple different ones and got a similar result—early nineties (92-93). There are still some things I can improve, but overall I was pleasantly surprised by the result. Knock on wood!

Running these longevity tools may still not be sufficient to calm your fears of running out of money. Who knows, perhaps you decide to move to a Blue Zone country, adopt a healthy lifestyle, and make it past 100—outliving these calculators’ expectations. But, as Perkins notes, for many different fears you can usually find an optimal insurance product. In the same ways that you understand the importance of life insurance to protect your family if something happens to you, you can also consider the reverse insurance—protecting against longevity risk.

Annuities are an insurance instrument that can guarantee income payments for life, effectively addressing the risk of outliving your savings. An important message of the book is that we shouldn’t try to become our own insurance agent, which is inefficient and expensive. In this case, trying to insure our own longevity risk means over-saving and over-working many years in our career. Given their ability to pool risk from a wide range of insurees and cancel out errors on both sides, insurance products—in this case annuities—are a much more cost-effective way to address this concern.

The message is clear: don’t keep every dollar “just in case”—insure against those cases instead, and spend the rest on maximizing fulfillment when you are still healthy. Whether it is annuities, long-term health care insurance, or something else, there is an insurance solution more optimal than individual over-saving. If you think the insurance is expensive, try to estimate the cost of over-working several years of your life to become your own, inefficient insurance agent.

Experiences with your loved ones are your true legacy. Photo by Juliane Liebermann on Unsplash.

8. Experiences, Not Inheritance, Are Your True Legacy

Many people say they work long hours for their family or for their kids. But, once you’ve reached what is enough, what is actually better for your for your kids—to have more money or to acquire more lifetime memories of time spent together?

Perkins is crystal clear here: your true legacy isn’t your estate—it’s your presence and the experiences you managed to share with your kids. The trips you took together, the evenings spent playing, the lessons you taught by living by example. Research backs this up—adults who recall high parental affection in childhood demonstrate better mental and physical well-being throughout their lives. Isn’t this the best possible legacy to give your kids?

Instead, many people overwork and sacrifice time with family—a core warning in Die With Zero. They miss out on spending time with their kids, and then leave them an inheritance when they are older adults that no longer need it. I did warn you, this book has quite a few eye-opening lessons.

The takeaway is not to assume every additional hour worked benefits your family. In some cases, and after a certain point, it’s just another hour you were not there for them.

Are you living in “autopilot”? Photo by Nathan McBride on Unsplash.

9. Stop Living on Autopilot: Spend With Purpose

As illustrated in several examples above, a lot of common financial behavior is driven by inertia. We are conditioned to save, invest (hopefully), and retire around age 65. But we often do so without questioning whether those paths make sense for us individually. This is also at the core of the FIRE movement when approached intentionally—not as an escape, but as a way to step off “autopilot” and actively design your preferred lifestyle.

We should challenge this default setting, step off “autopilot”, and ask whether we are aligning our lives with our values and seeking the maximum fulfillment from life.

Money has a diminishing utility over time. A dollar spend in your 40s—when your health, energy, and capacity for adventure are still high—may bring you far more joy than one spent in your 70s. Remember, the key question is not how much to spend, but when to spend it—more on this and time bucketing further below.

Perkins also makes a compelling case for buying back your time. If you have the means, he recommends outsourcing time-consuming or tedious tasks (e.g., cleaning your home). This is often a very high return-on-investment decision, especially given that research shows that money spent on time-saving activities makes us more content, regardless of income level. Time, after all, is our most limited resource.

Switching off the autopilot means asking yourself regularly—am I living with purpose and intentionally, or just following the crowd blindly?

Limone Sul Garda, Province of Brescia, Italy. Photo by Charleen Vesin on Unsplash.

10. Use Time Buckets to Plan Life by time intervals

A key actionable idea in Die With Zero is time bucketing—the practice of segmenting your future life into intervals (e.g., 5 years) and intentionally allocating the experiences that best fit into each window—after accounting for the interplay and dynamics of time, health, and money.

Some goals can wait, but others have a short shelf life. Write down all the activities and experiences you’d like to pursue (i.e., your bucket list) and try to allocate them on a 5-year interval timeline. This exercise requires prioritizing certain experiences over others, and helps you understand how the enjoyment of each one will change as our health gradually deteriorates over time. A week-long mountain trek might make most sense in your 30s, a wine tour through Italy in your 50s, or hosting a multi-generational family reunion in your 60s.

Time bucketing is not a static exercise. As your interests, health, and other circumstances change over time, so will the list of experiences. That is completely normal, and we should see this as a living document—its purpose is only to make us more intentional about our choices and to maximize the fulfillment of our experiences, not that we stick to some rigid plan. We can always revise our time bucketing draft, as we are exposed to new opportunities or as we change as people over time.

Hopefully, this approach gives you a sense of urgency and clarity. Our time here really is quite limited, and the time when we enjoy good health even more so. When you realize this, it stops you from deferring gratification to the future and to design a life you will be proud of in your old age.

When should we stop growing out net worth? What should be our portfolio target for early retirement? Photo by Carlos Muza on Unsplash.

11. When Should You Stop Growing Your Net Worth?

If you decide to “aim for zero”, your net worth should reach a peak at some point. In the FIRE community there is a general aversion towards dipping into the principal, which often leads to very conservative withdrawal strategies. The problem with this approach—even more so for Chubby or Fat FIRE enthusiasts—is that, as mentioned previously, it is being inefficient (or even wasteful) with your life energy. Again, if you make it to the grave with $2-4M net worth, well, congratulations—you are the richest person in the cemetery, but wasted a lot of time, energy, and fulfillment during your life.

So, if you acknowledge that at some point there must be a peak in net worth, then the following question is about figuring out when this peak should take place. It depends, again, on your personal circumstances, in particular your health and lifestyle. Perkins suggests to consider a 45-60 year old bracket—if you are in the physical condition of an athlete and expect extraordinary longevity, then you should probably aim for peaking your net worth at about 60 years old. In contrast, if you are a smoker with health issues in your family history, then maybe you should set the peak around 45. Everyone else will fall in between these two extremes.

In practice, Perkins recommends that everyone should estimate their survival threshold—the amount needed to cover their basic expenses for the remainder of their life. The book suggest the following formula: the number of years left to live—which you figure out after playing around with different longevity calculators—times the annual expenses needed for survival. This is then multiplied by 0.7, a rule of thumb that accounts for the portfolio’s growth over time.

So, if your basic survival expenses are $24,000, and you expect to live another 25 years, then 25 x $24,000 x 0.7 = $420,000. This is the portion you should initially set aside to cover the basics. But, tying back to the topic of longevity risk, it probably makes even more sense to secure these basic living expense through annuities. Then the next step is to figure out how to spend your remaining retirement portfolio over time on meaningful experiences—remember, again, that a disproportionate number of these will take place while you are still in good health. Having secured the basics through annuities may free you to spend the rest with more confidence.

Crucially, Perkins advises against thinking of the net worth peak as a number (unless it is someone who is under-saving for retirement, which is not the audience of this book—nor of this post). He advocates for thinking of it as a date—a turning point which reflects your life circumstances and health more than an arbitrary dollar target. Otherwise, it is too easy to slip into the “one more year syndrome”, or that an initial target of $1M suddenly becomes $2M, then $3M, and so on—until your best, healthier years have passed.

Photo by Austin Distel on Unsplash.

12. Take Smart Risks Early to Maximize Reward

Another important takeaway it to be aware of asymmetric risks appearing throughout your life and to use them in your favour. When you are young and unencumbered, the risk of failure is typically very low and the upside of bold moves is huge. This is how fortunes are made, and is why Perkins encourages to take these risks early in life.

An example of an asymmetric risk is a recent graduate from college starting out some high-risk entrepreneurial venture. It is only “high risk” in the sense that, statistically, a low percentage of start-ups succeed big, while most fail. But the downside is maybe just being unemployed a few months and starting out again, or, in the very worst of cases, perhaps spending a few months with your parents or relatives until you figure out what to do next.

When you are young, you have the ability to take this type of risks repeatedly—you only need to succeed once. I wish I had been more aware of this when I was young. Instead, I listened to the advice around me and went down the conventional route: study hard, become a respected professional (working for others), and hope for the best.

Even if your business “fails”, the experience gained often pays memory dividends. You’ll grow from the process, and likely look back with pride that you gave it your all, instead of having a sense of regret that you held back and took the conservative route.

The reason why many people don’t take these risks is because they exaggerate worst-case scenarios that are incredibly unlikely—homelessness, living under a bridge, permanent failure, etc. But the downside normally isn’t dramatic at all, so making an honest assessment can be very liberating. Remember that these windows don’t last forever. Your willingness and capacity to take risk shrinks over time, as more responsibilities appear on the horizon—don’t waste your boldest years playing it safe unless you are 100% sure that is what you want out of life.

Final Thoughts: Life Is About Fulfillment, Not Fortune

At its core, Die With Zero isn’t a book about dying—but a book about living and thriving. It’s provocative title is not meant literally—that you hit zero on the penny. Instead, it’s all about challenging the cultural obsession with accumulation, which taken to the extreme just means wasted life energy and lost experiences. It means retiring much later than you could have.

Readers are left reflecting on their current mindset and how it could change—from saving and deferring spending to enjoying fulfilling experiences now during their healthiest years; from hoarding wealth to harvesting life. Ultimately, the question is not only “how much should we save?”, but, more importantly, “how do we want to feel when we look back on our lives?” Do we want to feel proud at having lived fully or feel regret at having settled for surviving comfortably?

Photo by Sacha Verheij on Unsplash.

Die With Zero: Personal Reflections and Limitations

Is Die With Zero a good book? In my view, absolutely—especially if you tend to be an over-saver or lean heavily toward the FIRE mindset. If you either struggle to spend money or are too focused on the “positive impact” that deferring spending today will have in the future, then this book is exactly what you need to find a more balanced ground.

I feel like I read this book at the right moment. Overall, I’m very happy to have embarked on our Financial Independence journey. Having enforced a very high savings rate over the last years has allowed us to make choices that would have otherwise been difficult, e.g., working part time when kids arrived into the picture or recently quitting my job to pursue a more entrepreneurial route.

After following this Financial Independence journey for about 7 years, we are in a privileged situation. We really can allow ourselves to take the foot off the gas a little bit. We can reduce our savings rate and make sure we are not missing out on important milestones that come with a growing family. Reaching the FI goal a couple of years later doesn’t really matter in the grand scheme of things—what matters is that we fully enjoy the journey and don’t look back with regret.

While Die With Zero is a compelling read, one common criticism is that it lacks implementation detail—offering powerful ideas but fewer practical tools or case studies for applying them. The book lays out very convincingly the “why” we should aim to die with zero, but the “how” is sometimes vague—it is more of a philosophy and mental model, and less of a manual.

The author is clearly a quantitative wizard—he successfully traded over a billion in profit in a previous company—and it would have been fairly easy to include several complete case studies to exemplify how to implement the whole process from start to finish, i.e., from deciding on your minimum survival spend, to setting your target net worth peak, and how to allocate your spending over the years depending on your time buckets.

I am aware there are many variables at stake and that the design may vary substantially from person to person; but still, having some examples as reference would have been very helpful for the reader to think through the whole process and how it could apply to them.

Despite this limitation, the book clearly succeeds at what it sets out to do: reframe how we think about money, time, and purpose. This can be a potentially life-changing read for you, and I highly recommend you to read it if you haven’t already. In the end, this book isn’t about spreadsheets or safe withdrawal rates. It’s about maximizing the only thing we all run out of—time.

Real wealth is the memories made, relationships nurtured, and joy experienced. So, plan intentionally, yes; but also spend wisely. Certainly don’t wait to live, since, as Perkins remarks, “the business of life is the acquisition of memories”.

If you want one practical takeaway: write 10 experiences you’d regret missing, then assign each to a 5-year “time bucket.” That simple exercise is one of the core messages of the book.

If this resonated and you want to apply it:

👉 Start here: our Start Here guide for Financial Independence.

👉 Run the numbers: estimate your timeline to Financial Independence with the FI Calculator (free for subscribers).

👉 More life-changing books: Your Money or Your Life, The Psychology of Money, The Little Book of Common Sense Investing.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimer: I am not a financial adviser, and the content in this website is for informational and educational purposes only. Please consult a qualified financial adviser for personalized advice tailored to your situation.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The book encourages you to align your money, time, and health to live a more fulfilling life—by spending on meaningful experiences when you're best able to enjoy them, rather than deferring everything to old age.

-

It’s especially valuable for over-savers, high earners, and FIRE followers who may be delaying gratification too long and risk missing life’s most rewarding moments.

-

Not exactly. It means intentionally using your money to maximize fulfillment across your life—not dying with a pile of unused wealth you could’ve spent on joyful experiences.

-

Yes. The book isn't anti-saving—it’s anti-over-saving. It encourages securing your future first, then shifting focus to enjoying your wealth during your healthiest years.

-

Memory dividends are the lasting emotional returns from past experiences. Like compounding interest, memories give joy over time—so earlier experiences are more valuable.

-

He argues that giving money earlier—while your loved ones can really use it—is far more impactful than waiting to pass it on after death. Late-life inheritances often come too late.

-

That’s a valid concern. Perkins suggests solving this with tools like annuities and long-term care insurance, rather than hoarding money “just in case” and missing out on life.

-

Time bucketing is a planning method that helps you schedule experiences by age group—matching your money and energy to the right life phases (like doing adventure travel in your 30s, not 70s).

-

Definitely. It encourages creating shared memories with your children and loved ones. In fact, your true legacy isn’t money—it’s the time and experiences you give your family.

-

Start by defining what “enough” means for you. Use time buckets, calculate your basic spending needs, explore annuities, and reflect on which experiences you don’t want to miss.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles: