Germany’s new Frühstart-Rente Shows the Power of investing Early

The historic Reichstag building, which houses the German parliament in Berlin. Photo by Aron Marinelli on Unsplash.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Germany’s Frühstart-Rente: A Small Pension Seed with Big Ambitions

Germany is about to launch a simple but symbolically powerful policy with global relevance: starting in 2026, the state will pay €10 per month into a dedicated investment account for every child aged 6 to 17. This “Frühstart-Rente” (“early-start pension”) is designed to stay invested until retirement, letting compounding do the heavy lifting over decades. The Frühstart-Rente is Germany’s new child-pension scheme aimed at encouraging private pension investment from an early age.

Although the amounts contributed by the state seem trivial at first glance, the long time horizon, tax deferral, and potential for families to top up contributions could substantially change the picture. More importantly, it’s not just about the numbers. It’s also a test as to whether Europe’s traditional pay-as-you-go (PAYG) systems could be complemented by early exposure to capital markets. It’s also about setting the seeds for a cultural shift—one that encourages investing habits and planning for the future.

In this article, we’ll explain what the Frühstart-Rente is, show with real numbers how a small monthly amount can grow massively through compounding, explore behavioral and design challenges, and look at why this policy matters well beyond Germany.

A child planting a seed will have time to watch the tree grow. Photo by zhang kaiyv on Unsplash.

How Germany’s Frühstart-Rente Works: A Bold Cultural Experiment

Germany’s pension system—like most in Europe—relies primarily on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) model: today’s workers finance today’s retirees. With the working-age population shrinking relative to retirees and with life expectancy rising, pension systems across Europe are under growing strain.

The Frühstart-Rente aims to plant a small yet potentially powerful seed. From 2026, every child enrolled in the German school system between the ages of 6 and 17 will automatically receive €10 per month in a personal investment account until they turn 18. The reason for starting at age 6 is that it aligns with the beginning of compulsory education, making it administratively simple to link enrolment data and open accounts.

The policy stops at 18 to mark the transition to adulthood, after which young people can—and should—continue contributing voluntarily. The annual cost is estimated to be around €1 billion—a minuscule amount when compared to Germany’s public spending. As we’ll see in further sections, the amounts are small but meaningful, given the power of compound interest over many decades.

Still, the German coalition government is betting more on the cultural and educational impact rather than the fiscal support itself. Let’s be clear—this alone will not save the pension system, but it is an exciting step in the right direction

This experiment is globally relevant and potentially applicable in other countries: a small state contribution combined with early capital-market exposure to build a habit and culture of investing early. It really does represent a noticeable shift from “the state will take care of you” toward “the state will give you a head start, but you must care for your future, too”. It encourages financial literacy and personal responsibility, rather than passive reliance on the state.

There are still many unclear details that need to be decided on. For instance, policymakers have not announced who will manage the accounts, whether the investments will default into index funds or be actively managed, or how families can choose or switch between providers. In addition, there may be legal constraints that limit the state’s ability to favor a specific ETF, but they could still set criteria-based defaults—for example, low-cost, globally diversified fund.

The final choices on these details and others will likely determine whether the €10 seed flourishes or withers in fees, actively-managed funds, and complexity.

There is substantial uncertainty around how the scheme will work in practice. Hopefully it ends up being something simple, transparent, and low cost. Photo by TabTrader.com on Unsplash.

The Power of Compounding: Why Starting Early Matters

The upside of this policy is not about the €10 itself, but about demonstrating the power of time and compounding. Using a 7% real return (i.e., adjusted for inflation), a child who receives €10 monthly from age 6 to 17—a total of €1,440—and then lets it grown untouched until age 70 would end up with roughly €82,000 in today’s purchasing power. The original amount provided by the state is multiplied—thanks to compound interest—by a mind-boggling 55.

When I ran these numbers for my own kids, it really hit me: even without adding a cent ourselves, they could have tens of thousands waiting for them in retirement. Imagine if we topped it up with modest contributions.

This is an illustration of the exponential effect of compounding over 5-to-6 decades. Compare this with starting contributions at age 18 instead. If we had the exact same contributions over an equivalent 11-year period (18-29) the retiree would have €60,000 at 70—more than €20,000 less. In other words, starting early has a huge effect and can beat saving more later.

This long time horizon is exactly the kind of structural advantage that Financial Independence strategies try to harness—starting early and letting compounding do most of the work.

To put this in perspective, if the same person simply continued contributing €10 per month—an insignificant amount—all the way to age 70, the portfolio would grow to around €132,000 in real terms. And if the family contributed €30 per month from the very start—for example, €10 from the state and €20 from parents—and then the child maintained that same €30/month contribution into adulthood, the portfolio would reach a striking €440,000 by age 70.

These scenarios—depicted in Figure 1 below—highlight how a very modest increase in monthly contributions, sustained over decades, could multiply the outcomes several times over.

Figure 1: Long-term portfolio growth under three contribution scenarios (7% real return). The red line shows the baseline (€10/month, 6–17 only), the green line shows continuous €10/month contributions to age 70, and the purple line shows boosted contributions (€30/month from age 6 onward). The three scenarios reach about €83K, €147K, and €442K, respectively, by age 70.

The tax deferral also helps the compounding. Normally, German ETF investors face the Vorabpauschale, a small annual advance tax on accumulating funds and the Abgeltungsteuer (25% plus surcharges) when selling stocks. In the Frühstart-Rente, though, these annual taxes would be deferred until retirement withdrawals, which allows returns to compound tax-free.

For many retirees, their taxable income will also fall into a lower bracket (compared to the traditional flat 25% plus surcharges as capital-gains tax), further reducing the eventual tax bill.

But if time is so important, why not start from birth? The official reason is the administrative simplicity: every child starts school at age 6, making it easy to automatically enrol entire cohorts. While starting from birth would certainly be better for the 70-year-old retirees, it’s administratively more difficult and would increase the overall cost by around 50%. Given the testing nature of this scheme, the government is likely looking to limit its fiscal exposure.

If successful though, this would be the next logical step once the program proves its worth. For now, policymakers are starting where the data infrastructure is strongest.

The math is powerful, but numbers alone don’t guarantee success. That depends on how people actually engage with the scheme.

Will People Engage with Frühstart-Rente? The Behavioral Gap

Not everyone is convinced this policy will achieve its cultural goals. Specifically, it’s unclear whether this passive transfer by itself will boost motivation to save or to improve financial knowledge. Some experts argue that evidence from similar schemes shows that passively receiving money doesn’t necessarily translate into higher engagement or financial literacy unless it’s combined with education, further nudges, or matching incentives.

On the other hand, proponents argue that the mere visibility of a dedicated investment account from childhood can normalize saving and investing behavior over time, even if initial engagement is passive.

Bridging this behavioral gap is important. One option could be to integrate financial education into the school curriculum, teaching students about their accounts, how to manage them, and the basics of financial investing. Another could be to provide opt-in matching contributions for families—for example the state matches the first €X/month contributed by parents.

Setting a good default fund type and contribution level can dramatically increase its success. This reminds me of the ideas found in Richard Thaler’s Nudge: policies should allow the freedom for participants to make changes and choices, but there should be a solid default option for those who don’t wish to. Applied to this context, the default should be a low-cost, globally-diversified fund. It should not be left blank.

Digital tools may help too. App nudges—for instance, with notifications that explain portfolio progress, show long-term projections, or prompt parents to top up—could keep accounts from being passively forgotten. Even small visualizations like “your €1,440 could become €82,000” could help change saving behavior over time.

In my view, this policy may not only shape children’s financial futures—it could also indirectly spark a learning effect among parents. Think about it—by setting up a basic MSCI World ETF or similar low-cost fund for their 6-year-old, many parents may be prompted to build their own financial literacy and even mirror the same simple, long-term investment strategy for themselves.

This policy is both a financial and cultural seed. But seeds will need water to grow—in this case, the success of this type of policies will be determined by how successfully they manage to have participants actively engage and take control of their accounts.

We need a culture that normalizes investing from an early age—hopefully this scheme or a follow-up one contribute to solving the challenges surrounding our pension systems. Photo by Y M on Unsplash.

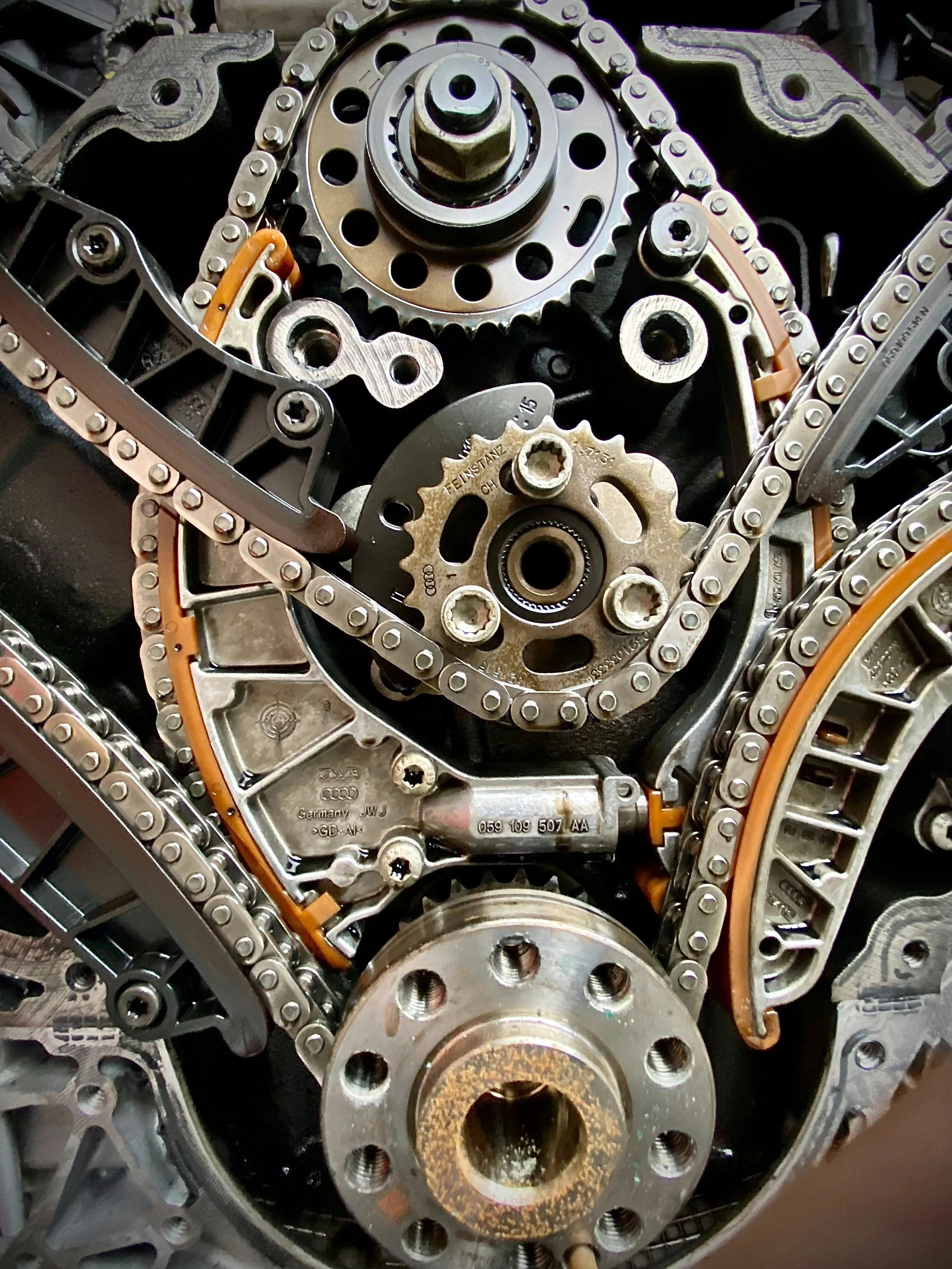

Investment Design Will Make or Break the Frühstart-Rente

The long-term success of the Frühstart-Rente will depend on how the money is invested. A low-fee, internationally-diversified ETF-based child pension account seems like the obvious default, with glidepaths that gradually shift towards higher shares of bonds as retirement nears. In other words, trying to mirror something similar to target-date funds.

High fees should be discouraged. Without fee caps, higher charges by actively-managed funds could easily eat away half the returns over decades. Of course, provider neutrality matters legally, but defaults can be defined by objective criteria (cost, diversification, and transparency) rather than naming a single index.

The tax treatment may be another key differentiator. In this scheme, all taxes are deferred, which means each euro of return can be reinvested automatically and compound until retirement. Upon withdrawal at 67, or likely later, the payout is taxed as pension income—often at a lower marginal rate than during working life. This is a subtle but powerful advantage, especially over multi-decade horizons.

Finally, engagement and simplicity are critical. If families find the system either opaque or too bureaucratic, co-participation is likely to be low. If, on the other hand, they receive simple dashboards, clear nudges, and easy ways to add their own contributions on top, the scheme could build momentum very quickly.

The legal challenge may be balancing the freedom of choice with protective defaults—ideally ensuring children don’t end up in an expensive, actively-managed (or very speculative) product by default. That would defeat the whole purpose of the initiative. Freedom should be granted for those wishing to make their own long-term mistakes, but the default should be rock-solid for anyone else.

The Frühstart-Rente aims to normalize equity investing from childhood. Photo by Вадим Биць on Pexels.

Germany’s Pension Reforms and the Role of Frühstart-Rente

Like other developed countries—and European ones in particular—Germany’s demographic challenge is acute. The ratio of workers to retirees is shrinking, and the statutory pension is already strained. German pension reforms increasingly focus on mixing public PAYG with private capital-market mechanisms, and the Frühstart-Rente is part of that shift. It is not designed to plug the fiscal gap; its €1 billion annual cost is symbolic next to the scale of the existing PAYG system.

Instead, it aims to normalize equity investing from childhood, create long-term supplemental savings, and signal a cultural shift towards a higher degree of personal responsibility alongside state support.

The policy is part of a broader reform package. Germany recently introduced the “active pension” (Aktiv-Rente), allowing retirees to earn up to €2,000/month tax-free while drawing their pension. The measure intends to keep older workers longer in the labor market, i.e., continuing to pay pension insurance contributions. The government is also debating raising the retirement age further, adjust contribution rates, and building a new, state-backed equity fund. In this broader context, the Frühstart-Rente is more of a long-term project—sowing seeds now for harvests in many years to come.

Its implementation will take time. Although there are still many open questions to resolve as of mid-October 2025, the scheme is set to launch in 2026. The first cohorts to receive all 12 years of payments will finish in 2038. It will take time for policymakers to assess whether there have been meaningful behavior changes as intended—also perhaps for the parents that mange them.

If successful, this small policy shift could inspire similar experiments across aging societies worldwide. The idea is not for them to solve challenging issues related to pensions overnight, but to change the cultural landscape and plan capital-market habits early.

For families pursuing Financial Independence, this kind of early investing infrastructure could become a powerful foundation to build generational wealth and reduce future financial pressure.

Let’s see what comes out of it. Personally, I’m really excited to manage it for my kids and use it as an educational opportunity with them.

💬 If your country launched a similar child pension scheme, would families actually engage—or just forget about the accounts? What kind of nudges or features would make you take it seriously?

👉 New to Financial Independence? Check out our Start Here guide—the best place to begin your FI journey. Subscribe below to follow our journey.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on money, purpose, and health, to help you build a life that compounds meaning over time. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access our free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The Frühstart-Rente (“early-start pension”) is a new scheme launching in 2026 where the German government contributes €10 per month into an investment account for every child aged 6 to 17. The money is invested until retirement, aiming to encourage private pension saving from an early age.

-

Yes. Every child enrolled in the German school system will have an account automatically opened, and the state will deposit €10 each month from age 6 until 18, totaling €1,440 before investment returns.

-

By giving children an early, tax-deferred investment account and encouraging families to contribute alongside the state, it blends state support with private capital-market participation.

-

Assuming a 7% real return, the state’s €10/month from age 6–17 could grow to around €82,000 by age 70. Increasing contributions to €30/month and continuing them until age 70 could provide €400,000+ portfolios.

-

Germany ties the scheme to school enrollment for administrative simplicity and to control fiscal costs. Starting at birth would increase costs by 50% and require more complex implementation.

-

The government hasn’t finalized details. Many expect low-fee, globally diversified ETFs as the default. Questions remain about provider selection, glidepaths, and fee caps.

-

Yes. All investment returns are tax-deferred until retirement. This allows compounding to work tax-free for decades, and retirees often face lower tax rates upon withdrawal.

-

Yes. Parents and later the children themselves can top up contributions. Our scenarios show that boosting contributions to €30/month from age 6 can result in portfolios exceeding €400,000 by age 70.

-

The Frühstart-Rente is part of a shift towards combining public pensions with private capital-market savings. Other measures include the “active pension” and proposals for a state-backed equity fund.

-

Yes. Similar ideas have existed in the UK and Nordics. Germany’s scale gives this experiment global relevance, especially for aging societies looking to foster early investing habits.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles: