The Case for Being a Generalist — In Work, Skills & Life

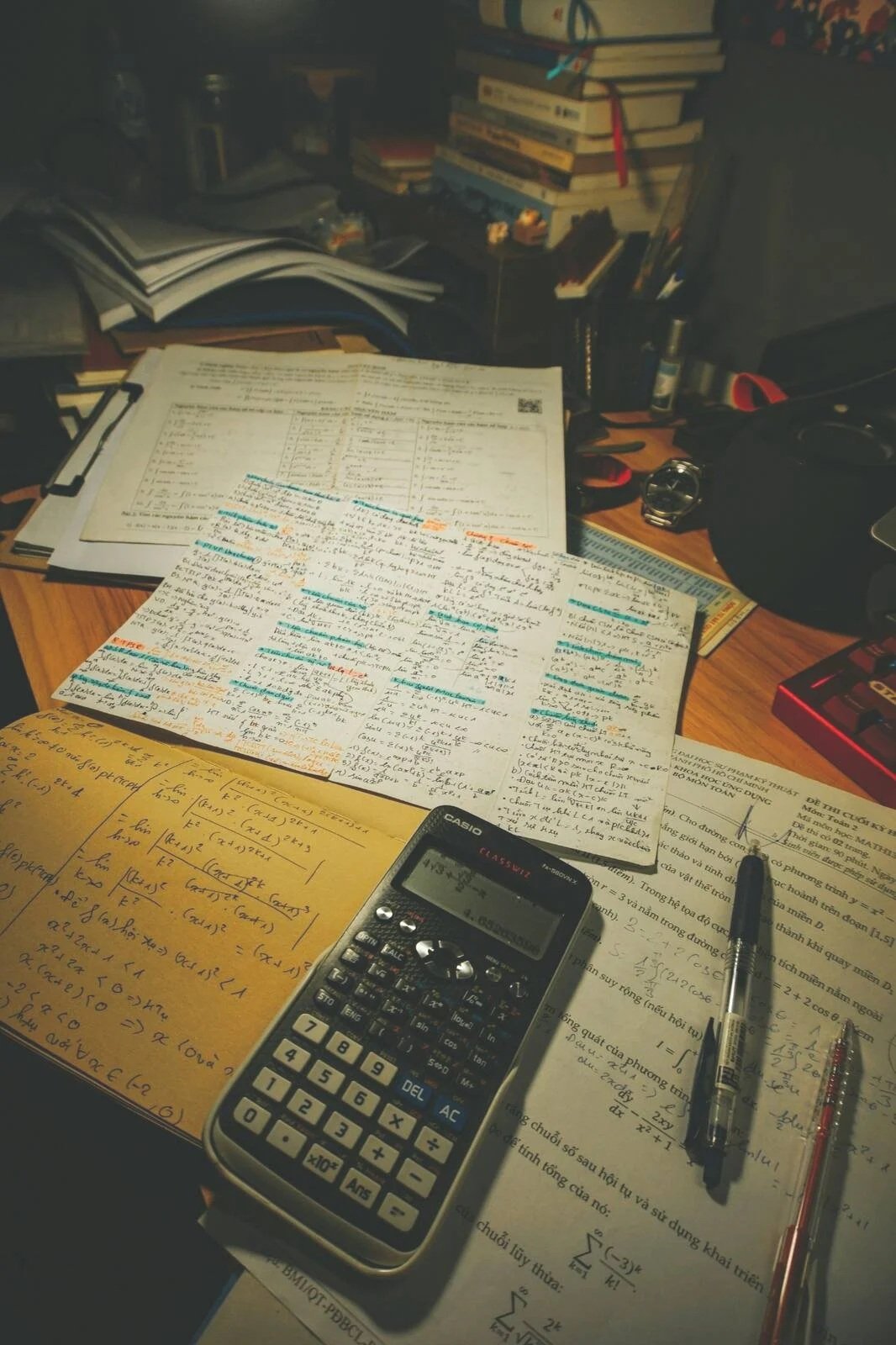

Embracing a generalist lifestyle—where you figure out and solve your own problems, rather than outsourcing them—can bring a lasting sense of pride and fulfillment. Photo by Austin Ramsey on Unsplash.

TL;DR — Specialists vs Generalists

🎯 Specialists: deep expertise, higher earnings potential, efficiency, competitive edge in stable fields

🌍 Generalists: adaptability, resilience, wider life satisfaction, autonomy in daily living

🔀 Financially, best long-term career model: T-shaped—one deep skill plus range across others

📈 Generalists thrive when industries shift, roles change, or FI allows reinvention

🏛 Specialists excel in stable systems—but are more fragile to disruption & obsolescence risk

❤️ In life, generalism often leads to richer experience, capability, and fulfillment

Generalist vs Specialist: What’s Better for Work, Life & FI?

In today’s article, we break down whether it’s better to be a generalist or a specialist—in work, skills, and everyday life. You’ll learn the pros, cons, financial implications, risks, and how generalism shapes fulfillment, antifragility, and Financial Independence (FI) resilience.

While society tends to reward specialists in the short term, individuals pay the cost on a personal level. Most people choose a narrow path before they’re old enough to understand themselves—and often spend decades inside careers they dislike. Here we explore an alternative: a broader, more capable life built on curiosity, skill, and reinvention—both in the workplace and in life.

Throughout the article, you’ll see these two domains separated clearly—generalism in daily life (self-reliance, skills, autonomy) and generalism in work (adaptability, multi-career reinvention). Each share things in common but also come with different benefits and trade-offs.

Why We Became Specialists — And What It Cost Us Individually

Modern society is built on specialization—a concept famously articulated by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations (1776). There he described how productivity skyrockets when workers divide tasks rather than each producing an entire product themselves.

Industrialization further amplified this logic. Emerging factories needed hands repeating single tasks, not minds wondering across many different ones. Over time, we slowly optimized society for output, not individual sovereignty. We rewarded narrow depth rather than broad capability.

Education systems continued to reinforce this logic. In much of Europe, a teenager essentially chooses their lifelong career and identity by 18—whether they want to be a lawyer, an architect, a dentist, or an economist—long before they’ve lived enough to understand themselves and what they want out of life. It’s true that some countries approach it differently; for instance, the US liberal-arts model delays this specialization with a broader education during the first four years of college.

Still, even in the US, the pressure is there: pick a major, pick a field, pick one thing. As we discussed in our post on James Suzman’s book Work: A History of How We Spend Our Time, this contrasts sharply with how humans have behaved for 99% of our shared history: in both hunter-gatherer and agricultural societies, people routinely practiced dozens of different skills—hunting, toolmaking, basket-weaving, food production, and many more.

For the majority of our human experience, work has been something fluid, seasonal, varied. We became specialists very recently because an emerging system demanded it, not necessarily because humans have evolved over centuries or millennia for it.

Work culture today often seals the individual’s identity. Since you only do one thing you become what you do—an accountant, a surgeon, an engineer. Depth in a single, narrow field naturally becomes a strong part of your identity, while career breadth becomes a distraction. And yet humans had historically thrived as generalists. Modern specialization may indeed produce higher GDP, but it doesn’t necessarily produce more fulfilled humans at the individual level.

Lawyers are classic examples of career specialists—they often have very deep expertize in a narrow subject. Photo by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash.

Benefits of Being a Generalist in Life — Capability, Joy & Autonomy

And yet there is something profoundly satisfying about learning a completely new skill—fixing a bike tire, restoring a piece of furniture, painting your home, learning to preserve foods, or installing the curtain rails. The learning curve is often steep at first, but it’s in that steepness where humans find engagement and joy.

Neuroscience supports this: novelty and challenge trigger dopamine and increase engagement, and the process of effortful learning tends to produce more durable satisfaction than passive consumption. As Dr. Huberman explains, the brain reinforces behaviours that involve struggle followed by progress—not just reward received.

Doing things yourself cultivates a sense of sovereignty—the kind you can feel in your hands. You look at the walls you painted and proudly remember the physical effort you put into it. Or you eat home-grown tomatoes and you almost taste the patience that went into it, the weather, and the soil. Those tomatoes feel like your own creation.

My wife and I could have certainly afforded to have a pro come in and paint out flat. They would have done it faster and the detailed finish would have been better. And yet, when we sit in the living room sofa and look at the wall we remember the shared challenge, effort, and story that went into the project. The value isn’t just aesthetic, but personal. Engaging in enhancing your capability breeds a sense of pride.

This is how skill becomes culture. When you fix something, you have not only learned or improved a skill, but also cast a vote for the type of person you want to become—someone resilient that can figure things out. The next time, it becomes easier, and soon it becomes normal and a part of who you are. You don’t outsource tasks straight away, but accept the challenge and try to figure things out for yourself.

When it comes to life skills, generalism isn’t just psychological—it can also be healthier and cheaper. This week I’m producing at home my first batch of fermented kimchi. Over the last few months, I’d become addicted to this very healthy fermented food, but was aware at the same time of how expensive this indulgence was. The underlying vegetables are dirt-cheap though—so why not try to ferment it at home? After all, we were able to do this for 99% of our history.

Generalist vs Specialist at Work — Career Resilience & Reinvention

Let’s now shift from generalism in everyday life to generalism in the workplace—where the rewards and risks look somewhat different.

It’s true that specialization pays well—but often comes at the cost of resilience and fragility. Of course, specialization can have its own beauty—deep focus, flow states, mastery, and sometimes solving problems at a world-class level. The point isn’t that specialization is the wrong path—specially if it’s clearly making you happy—but that a single lane may carry silent costs.

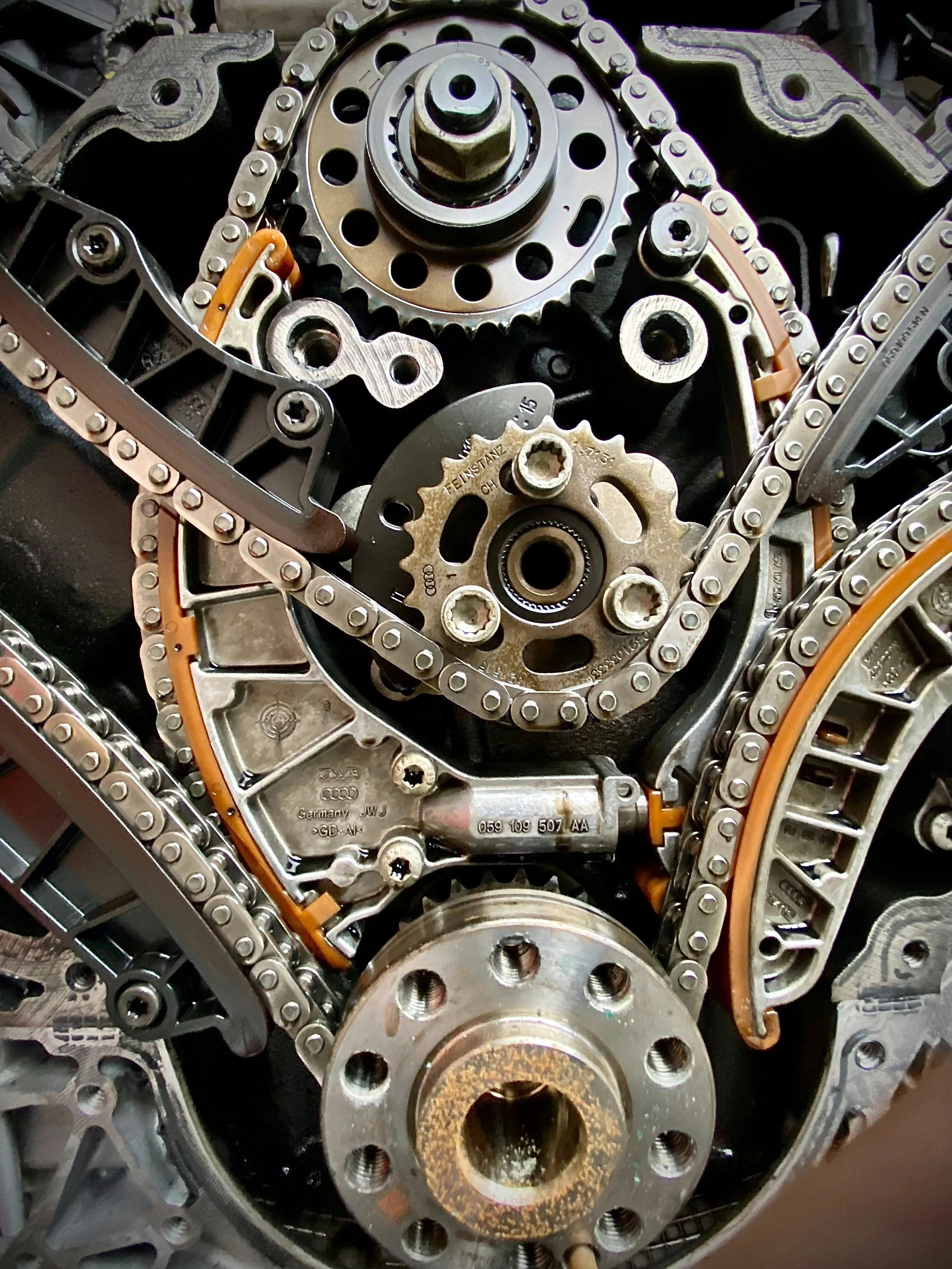

Many high-income careers reward narrow depth, for example, law, dentistry, medicine, or quantitative finance. But deep skills can also be fragile in a changing world. Think of how the ongoing AI deployment is already affecting many sectors. To illustrate, AI agents are increasing the quality of their code at an impressive speed—what will happen to those who bet on a deep coding specialization?

Or consider a very technically-proficient 40-year old, already 15 years into her career. She had offered until now impressive technical performance, but her company just hired 2 younger colleagues that can produce high-standard work at a fraction of the cost. There are certainly some risks involved in specializing too strongly without keeping an eye on the bigger picture or willing to change roles or career paths. The point is that, in many cases, one career and single identity can also mean one point of failure.

In contrast, generalists adapt better. Think of a product manager with leadership, communication, research, negotiation, and project-execution skills—this individual can adapt and move seamlessly across sectors as needed. A person with breadth can reinvent themselves more times. In a world of increasing disruption, adaptability could compound faster than expertize.

I felt this firsthand. Earlier in my career I was a (proud) specialist—I had deep knowledge in one technical-scientific niche and was highly respected for my expertise. And yet, ultimately, my profile was fragile. In science-based consulting, I noticed the generalist project managers—sometimes with almost no topical expertize, but with people, organization, and communication skills—tended to get more credit and advance faster than subject-matter experts.

It was a frustrating situation because I was aware I thrived as a specialist, and genuinely accepted the trade-off of “advancing” less in the organization but keeping my profile—which made my day-to-day enjoyable. Unfortunately, my company kept pushing me towards leadership and project management roles that I really disliked. What’s the point of going up the ladder if your setting yourself up for misery? In the end, I went down the project management route they suggested, and ended in burnout and me quitting the job.

Perhaps the ideal may not be pure generalism or specialization in isolation—but a T-shaped profile: having deep mastery in one domain (the vertical part of the T) supported by broad capability across other areas (the horizontal part). Depth earns in the short term, but breadth protects in the long term and makes us resilient.

For pursuing Financial Independence (FI) specifically, the path isn’t binary. Specialists often reach financial independence faster because deep expertise commands higher early-career income and accelerates compounding. But generalists tend to be able to sustain longer-term careers and be more resilient to industry changes—often they’re able to pivot seamlessly when one field saturates or disappears.

A financial analyst—a specialist—at work. Their deep expertize in a single field can make them fragile to sector changes or technological disruption. Photo by Campaign Creators on Unsplash.

The Downsides of Specialization — Risks, Fragility & Burnout

A recent Gallup poll reported that roughly 80% of global workers are unhappy at work—it’s not surprising that quiet quitting is on the rise. When you specialize early, you may optimize income but sacrifice exploration—one of the key disadvantages of being a specialist.

That can be for many the quiet tragedy of deep specilization: sometimes you feel like you’ve won the game but end up disliking the prize. And switching later on can feel expensive because of sunk costs (“What about all the training that went into this?”) and anchor identity.

Outside the work environment, outsourcing everything—gardening, repairs, technology, bike maintenance, cooking—creates comfort in the short term, but also dependence and a lack of resilience. I think sometimes of my parents, who call someone for every minor issue: a broken hinge, a software update, a leaky toilet. The more you outsource, though, the less you learn, and the more fragile life can become. Generalism and a willingness to learn outside of your narrow field protects you against fragility.

Specialist careers carry risk. Often you’re one job loss or industry collapse away from an identity crisis. Or, as we’re already seeing today, skills that took 20 years to build can be automated by AI in the blink of an eye. A life that is built on one talent may be efficient, but it’s also thin. Is there a better way?

This week I tried to ferment my first batch of kimchi—trying to learn new skill, save money, and improve my health. Photo by Micah Tindell on Unsplash.

How to Become a Generalist in life — Practical Starting Points & FI Lens

You don’t need to abandon mastery—you just need to reintroduce curiosity. Generalism is not about doing everything, but about being able to do something. A generalist FI-mindset doesn’t just save money—it builds antifragility.

Why not start by choosing one single skill to learn this month—repair those pants, fix the bike breaks, learn to ferment food, install the curtain rod, or build your own website?

Interestingly, one solved problem creates momentum. You feel emboldened by your success, and it becomes permission for attempting the next project on the list. You don’t have to overhaul your entire life—just focus on one single thing you can tackle this week.

In the work space, career generalism can follow a similar rhythm. In the long run, generalists may outperform specialists not by being better at one thing, but by being able to pivot when industries change. In a previous article, I also argued for the legitimacy of actively pursuing sequential careers—changing every 3-5 years not just your job, but your industry.

Not because you have to, but because you want to. It could provide enough time to learn deeply, contribute, and then pivot to another field with skills you can carry forward. Instead of 50 years in one lane, imagine the joy of looking back at 10 different careers.

And what a story that would make. Each career expanding—not restricting—your identity, capability, and connection. In an era of potentially extended longevity, not embracing multiple careers might be our biggest mistake—one we look back at with regret. It may soon be out of our control—current technological disruptions may change our career trajectories for us. The point is to embrace these changes rather than fight them, because, ultimately, they could be more enriching.

If you’re pursuing Financial Independence and wish to retire early, embracing generalism is a force multiplier. Financial Independence grants us time—the raw material for learning and capability. Adopting a generalist mindset is how a FI person becomes antifragile rather than just wealthy. Remember that you don’t need to outsource every single task just because you can.

You don’t need to be helpless with money, gardens, tools, or food. Capability is compounding, and frees you as much as your FI portfolio. Wealth protects you once you have it; capability protects you even before.

Personally, it took me some time to figure out that for many the ideal path is not to be the best at one thing—but competent in many, excellent in a few and always curious. Look around you and start small, perhaps try to fix one thing rather than replacing it. Grow some plant. Commit to repair that gadget.

For me, the next projects are fixing the brakes on my cargo bike and reinstalling a few defective curtain rails around the house. Writing this article has given me the nudge and motivation to do so—I hope it does for you too.

💬 If you could learn just one new life skill over the next 30 days, what would you choose — and why that one?

👉 Want to understand how to reach Financial Independence in your mid-40s? Check out what savings rate will get you there depending on age and current portfolio size.

👉 Looking to retire a decade or more early? Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free for email subscribers) to plug in your numbers and see how soon you could go into retirement.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimers: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Neither is universally better—specialists win in stable fields, generalists win in changing ones. Specialists maximize income early, generalists maximize resilience, option value, and adaptability over decades.

-

Generalists can switch careers more easily, solve a wider range of problems, and adapt when industries change. They tend to build confidence, autonomy, and antifragility—valuable for FI and modern work.

-

Breadth can come at the cost of deep expertise, slower income growth, and less early clarity. Without intentional skill-building, generalism risks becoming shallow rather than versatile.

-

Because uncertainty rewards flexibility. When markets shift, technologies change, or industries disappear, generalists pivot—while specialists may get trapped by sunk cost and identity.

-

Specialists achieve competence and earning power faster, especially in medicine, law, and technical fields. Deep mastery creates status, efficiency, and unique value—until conditions change.

-

A single skill also means a single point of failure. Burnout, automation, industry collapse, or changing interests can break a specialist career more easily than a generalist one.

-

Generalists often experience more novelty, movement, learning and autonomy—all linked to well-being and cognitive longevity. Specialists risk psychological narrowing and identity over-attachment.

-

Yes—the T-shaped model combines one deep speciality with supporting general skills. Depth earns money, breadth builds resilience. Many thriving people land here naturally.

-

Choose one small new skill to learn — fix, grow, cook, repair, build. Progress compounds. Identity follows action. A generalist life is built one capability at a time.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,103);

});

</script>