The FIRE Balance: When Saving More Stops Improving Your Life

Moments of time and connection are part of the real value Financial Independence is meant to protect. Photo by Krisztina Papp on Unsplash.

Reading time: 7 minutes

Quick answer

Saving and investing more is essential early on the path to Financial Independence because small structural decisions can shift your timeline by years. But over time, the impact of further optimization shrinks while the personal cost can grow.

Beyond a certain point, Financial Independence becomes less about maximizing every dollar and more about using money to gain time, autonomy, and flexibility. The real balance is knowing when saving more meaningfully improves life—and when it doesn’t.

What you’ll get from this article

✔ Why saving aggressively matters most early in the FI journey

✔ When optimization starts delivering diminishing returns

✔ The few financial decisions that shape your FI timeline by years, not months

✔ How priorities often shift after several years pursuing Financial Independence

✔ A practical lens for balancing future freedom vs present life quality

✔ How to think about FI as time autonomy, not just a portfolio number

TL;DR — When Saving More Stops Improving Life ⚖️💰

💡 Early optimization is powerful: big cost decisions can shift FI by years

📉 Later optimization weakens: small tweaks usually change FI by months

🏠 Housing, transport, and lifestyle structure matter far more than coffee cuts

🧠 Psychological costs rise when saving becomes over-optimization

⏳ Real wealth is time freedom, not just more money

🎯 FI works best as a balance between future security and present living

🔑 The goal isn’t the biggest portfolio — it’s the freedom to use your life intentionally

Financial Independence Starts With Money—But Doesn’t End There

Pursuing Financial Independence (FI) is often framed as a numbers problem: optimize expenses, increase savings, compound investments, and eventually reach a portfolio large enough to buy back your freedom.

But beneath the math and spreadsheets lies a deeper goal: autonomy. In my view, the real goal is not the final dollar amount, but the ability to redesign your daily life around your values, health, and interests rather than obligation or financial pressure.

This article explores a central question many people on the FI path eventually face: when does saving more stop meaningfully improving life, and how do you recognize the point where additional optimization matters less than how you choose to live today?

We’ll explore when financial optimization meaningfully accelerates Financial Independence, when it begins to deliver diminishing returns, and how to pursue FI in a way that expands freedom and optionality rather than restricting everyday life. I’ll also share how this balance has evolved in my own journey after nearly a decade on the path.

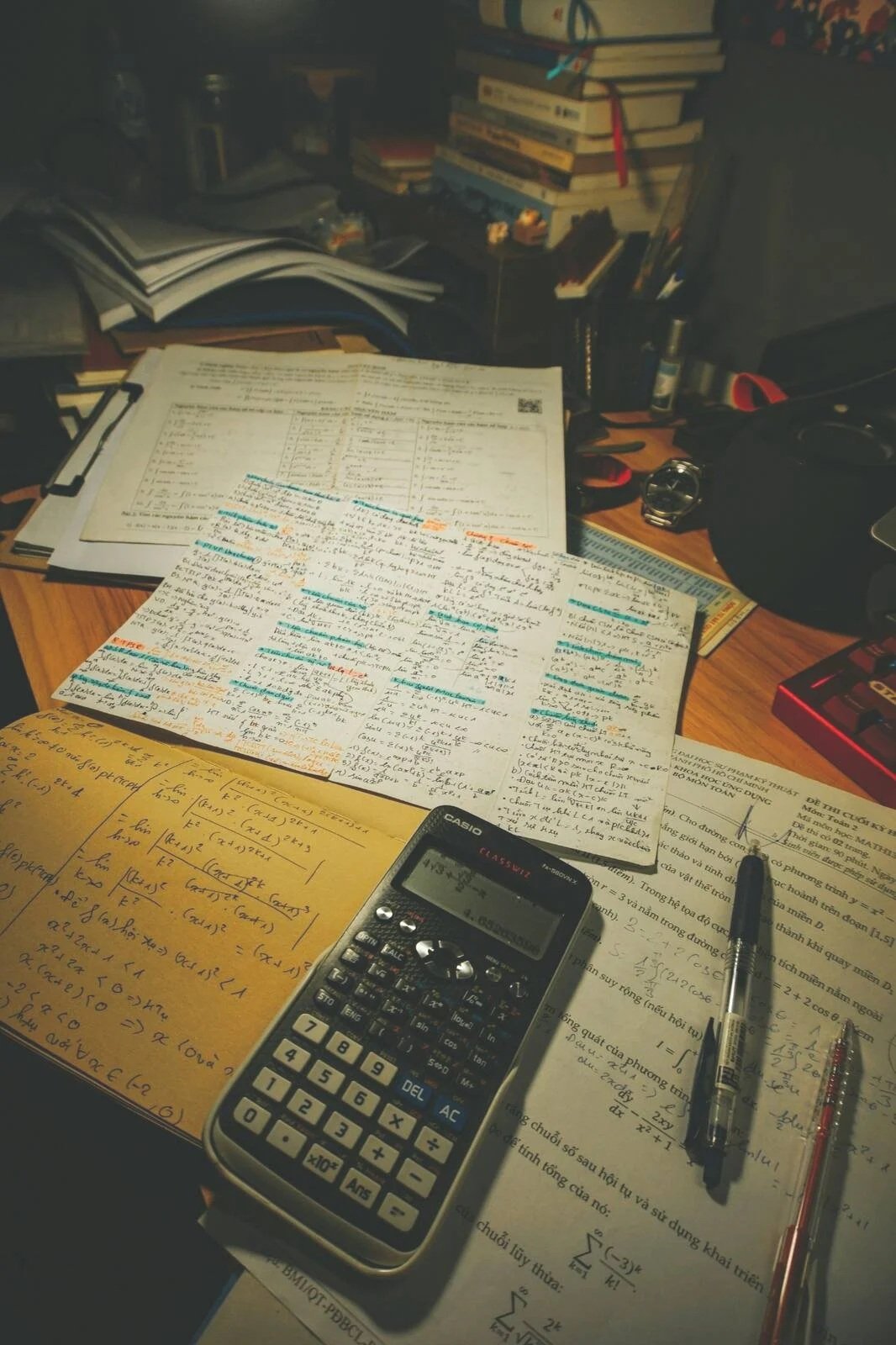

Careful optimization and long-term planning shape the early stages of the FI journey. Photo by Campaign Creators on Unsplash.

Small Savings Compound—But Time Changes the FI Math

In personal finance, the combination of multiple, small marginal improvements is undeniably powerful from a mathematical perspective. Going routinely through your monthly expenses and managing to consistently optimize small expenditures can compound into differences worth hundreds of thousands of dollars over several decades.

People often bring up the coffee example to illustrate this point. Imagine you’re in the habit of buying a takeaway coffee every morning on the way to work. It’s not something you necessarily derive much joy from—more like a routine you happened to fall into. If you saved those daily $5 and made your coffee at home instead, you would have about $110 extra per month to invest, which could compound to roughly $120,000 and $270,000 after 30 and 40 years, respectively.

The lesson at first glance is motivating. It doesn’t necessarily mean you should cut back on the coffee; the example simply illustrates that finding small areas to optimize recurring expenses can have a much larger financial impact over long periods than we intuitively would expect.

Consider the further example of ETF fees, which most of us will be less emotionally attached to than coffee. As we estimated in a previous article, the difference between a 0.30% ETF and a 0.07% ETF can leave you with about 6% lower net worth after several decades—again, typically amounting to hundreds of thousands for a seven-figure FI portfolio target.

The same pattern appears across many everyday recurring expenses. Negotiating a slightly lower rent or a slightly higher salary compounds over time. Choosing reliable second-hand cars instead of continuously financing new ones not only frees up initial capital but also reduces monthly costs for decades. Even routine categories like insurance premiums, mobile plans, or subscription services often contain easy savings.

Individually, none of these changes feels dramatic. But taken together and sustained over time, they can meaningfully reshape your financial trajectory toward Financial Independence. Optimization matters most in the early stages of the FI journey: cutting big costs and increasing savings rate at the beginning can shift the timeline by years, as small consistent decisions compound in the background and turn discipline into long-term freedom.

If you’ve never translated these decisions into an actual timeline to Financial Independence, it can be surprisingly clarifying to see how years—not just dollars—shift based on a few key choices.

Yet we don’t want to take this logic too far. While the impact of each individual decision on long-term net worth can feel dramatic—again, often hundreds of thousands of dollars—the emotional meaning of those gains looks different when translated into time to Financial Independence rather than dollars. Seen through that lens, the real-world impact is often more modest than expected.

For instance, in the ETF fee example, choosing the more expensive fund did translate into a six-figure lifetime difference. But when converted into the FI timeline, the delay was typically measured in months rather than years. Why? Because once a portfolio reaches seven figures, market returns begin to dominate behavior, and the portfolio itself can close surprisingly large dollar gaps in relatively short periods of time.

This reveals an important paradox: optimization is both powerful and limited. It is most powerful when it targets the few high-impact variables early in the journey, when your savings rate and biggest life expenses are still taking shape. But as the portfolio grows, further fine-tuning of small expenses produces rapidly diminishing returns, especially when weighed against the value of enjoying the journey itself. This is where the distinction between frugal and cheap spending becomes especially important.

In my view, one of the central challenges of FIRE is therefore not maximizing every spending variable indefinitely, but finding the right balance between financial efficiency and quality of life—an idea explored further in the concept of the Middle Path to Financial Independence.

Housing remains one of the most powerful long-term financial decisions affecting the FI timeline. Photo by Spacejoy on Unsplash.

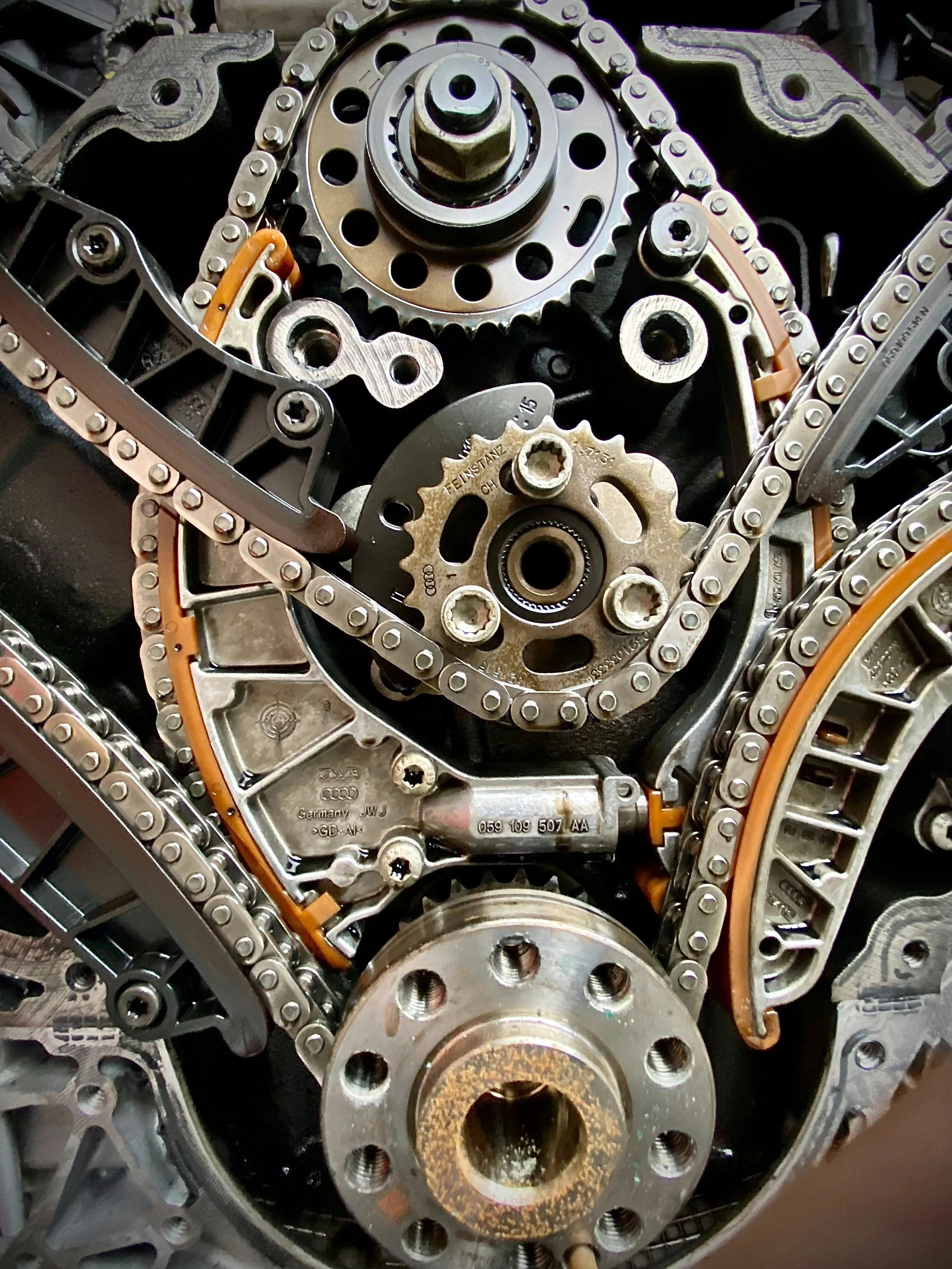

The Biggest Financial Decisions That Shape Your FI Timeline

If we agree that optimization is both powerful and limited, the next question is where that power really lies. Not all financial decisions are created equal; some reshape your entire trajectory towards FI, while others barely move the needle despite consuming a lot of our attention.

In practice, the largest and most durable gains usually come from a small number of high-impact variables. Housing costs, transportation, and food choices tend to dominate the impact on savings rate and long-term outcomes far more than tweaks on everyday spending.

For most households housing is the single largest financial lever. Whether you rent or buy, the share of income devoted to shelter largely determines how much remains available for saving and investing over decades. Small percentage differences really do compound enormously. Choosing a more modest home, delaying purchase in overheated markets, or renting while investing the difference in expensive cities can shift the FI timeline by many years rather than months.

Transportation sits close behind. Car ownership is often treated as a necessity and, in come cultures, a symbol of status. Yet the total lifetime costs of purchasing, insuring, fueling, maintaining, and replacing vehicles can easily reach multiple six figures. In contrast, living in a location that reduces or eliminates the need for a car can fundamentally change your financial trajectory. Deciding to use a second-hand car rather than a status vehicle can also have a very high impact.

A third, more complex lever to consider is food. It’s more complex, because spending patters around food are intertwined with health and social life, sometimes making this category emotionally loaded. But, over long periods, the difference between routine convenience-based spending and intentional, home-centered eating can be extremely large. This will vary a lot across households, but there are areas of synergy where you can manage to both lower expenses and eat more healthily.

In the end, pursuing Financial Independence is less shaped by perfect optimization in small decisions and more by prioritizing the alignments of a few structural ones—focusing first on the “big three.” Once housing, transportation, and core lifestyle habits are reasonably optimized, the marginal value of further optimiting and fine tuning coffee takeaways drops quickly, especially once you’ve reached later stages of the FI journey.

Food spending is flexible—small everyday choices can meaningfully influence long-term savings. Photo by Jep Gambardella on Pexels.

When Saving More Stops Improving Your Life

From my experience, there comes a point along the FI path when the mindset begins to change. The numbers may still look strong, the savings rate remains healthy, and the portfolio keeps growing in the background. Yet the practical benefit of further optimization gradually shrinks, while the personal cost of continuing to optimize starts to increase.

You begin to notice that changing another minor expense rarely changes the long-term financial outcome in a meaningful way. In this sense, I’m grateful to have recently come across the 0.01% spending rule, which provides a framework to reframe low-stake decisions. The idea is simple and aligned with what we covered in today’s article: if a purchase represents only a tiny fraction of your total long-term wealth, it may not deserve the same optimization energy as the big structural choices that truly shape your FI timeline.

Many FI folk report that, after several years of optimization and wealth accumulation, they gradually become more aligned with some ideas found in Bill Perkin’s Die With Zero. Setting yourself up for early retirement is still important, but enjoying the journey and engaging in what he calls “the business of acquiring life memories”—what life is ultimately all about—starts becoming the new goal to optimize towards.

For me, this happened very recently, after 7-8 years on the path to FI. The combination of wanting to enjoy family life while my kids are still young and realizing the diminishing impact of optimizing small expenses has allowed me to soften my path to FI. Personally, I find it worth delaying FI by two or three years in exchange for a higher quality of life today. For me, life’s most meaningful experiences are happening now—these are the years I will most likely look back on and cherish.

Of course, this trade-off will look different for everyone. For households still far from financial security, aggressive saving may remain the rational priority. The balance tends to shift only once stability is firmly in place. Either way, understanding roughly where you stand on the FI timeline can make these trade-offs feel more intentional and less uncertain.

I don’t think these realizations weaken the logic of pursuing Financial Independence, but simply refine them. Early discipline remains essential, because it creates the momentum and runway that allows for more freedom and flexibility to emerge later on. But once a solid foundation is in place, the goal can shift from gradually maximizing efficiency to enjoying an increased sense of freedom and optionality more wisely.

At that stage, the challenge stops being purely mathematical and becomes deeply personal. It’s centered on timing, relationships, and the recognition that some opportunities and experiences are bound to specific seasons of life. In that sense, easing off the gas over time isn’t a failure of discipline, but a sign that the journey is starting to serve life rather than the other way around.

And I think that was the deeper and most surprising shift for me along the FI journey: what began almost exclusively as a pursuit of efficiency and vague promises of freedom has slowly become a pursuit of intention and optionality. Not maximizing every single dollar, but using time and energy now in ways that feel aligned with the life I actually want to live.

If you enjoyed this article, here are some next steps:

👉 Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free, email unlock) to estimate your timeline to early retirement

👉 New to Financial Independence? Start with our Start Here to find the information you need

👉 Subscribe to The Good Life Journey (free tools & monthly newsletter, unsubscribe anytime)

💬 At what point does optimizing money stop improving life for you? Have your priorities shifted as you’ve moved along your FI journey? Share with us your thoughts in the comments.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing—with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

Check out other recent articles

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Saving strongly improves security and freedom in the early stages of Financial Independence, when increasing your savings rate can shorten the FI timeline by years. Later, once a portfolio becomes substantial, further cuts to small expenses usually change the timeline only by months. At that stage, quality of life, time use, and relationships often become more important than maximizing every dollar.

-

Small optimizations compound powerfully over decades, especially early in the journey. However, their impact declines as investment growth begins to dominate portfolio progress. This means early discipline matters greatly, but later on the focus often shifts toward maintaining balance rather than squeezing every possible saving.

-

Because Financial Independence depends not only on savings but also on market growth and portfolio size. Once investments reach higher levels, normal market returns can close surprisingly large dollar gaps quickly. As a result, even six-figure lifetime differences may shift the FI date only modestly.

-

Housing costs, transportation choices, and core lifestyle spending usually dominate long-term outcomes. Optimizing these structural factors can shift Financial Independence by years, while smaller recurring expenses often have limited effect later. Focusing on the biggest levers first is typically more effective than perfecting minor details.

-

Not necessarily. While higher savings accelerate progress, overly restrictive spending can reduce wellbeing and make the journey harder to sustain. Many people ultimately pursue a balanced approach that protects both long-term freedom and present-day life quality.

-

The idea behind the 0.01% rule is that purchases representing a tiny fraction of long-term wealth may not deserve intense optimization. Instead, decision-making energy should focus on large structural costs that meaningfully shape the FI timeline. This helps reduce mental friction while preserving overall financial progress.

-

Early progress is driven mainly by saving behavior and visible milestones. Later, portfolio growth becomes quieter and more abstract, while questions about time, purpose, and lifestyle become more prominent. This natural shift often changes how people define success within Financial Independence.

-

For some people, yes. Trading a small delay in FI for better health, relationships, or meaningful experiences can produce a higher overall quality of life. Because later-stage optimization has diminishing returns, modest timeline extensions may be a rational choice rather than a failure of discipline.

-

Money is the tool, but time flexibility is usually the deeper goal. As financial security grows, the value shifts from accumulation toward autonomy, choice, and control over daily life. This reframes FI from a strict retirement target into a broader form of personal freedom.

-

Start by optimizing the biggest structural costs early, when the impact is strongest. Then gradually allow more flexibility once savings momentum and investment growth are established. The goal becomes sustaining long-term freedom without postponing meaningful life experiences unnecessarily.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>