Was Time in the Market Warren Buffett’s Real Secret Sauce?

Warren Buffett’s wealth didn’t come from a late-life breakthrough, but from decades of compounding on an ever-growing capital base. Photo: Moneywise

Reading time: 7 minutes

Quick answer:

Most estimates suggest that over 95% of Warren Buffett’s net worth was created after age 65—not because he became a better investor, but because decades of compounding finally had enough time and capital to work. This article explains the math behind that claim, what it gets right (and wrong), and what ordinary investors can realistically take from Buffett’s story.

What you’ll get from this article

✔ How much of Warren Buffett’s wealth was created after age 65—and why

✔ Why time in the market matters more than talent for most investors

✔ How savings rate builds the base that compounding works on

✔ Why most investors quit right before compounding accelerates

✔ What Buffett’s story does and doesn’t teach ordinary investors

✔ How to apply these lessons without stock picking or market timing

🧠 TL;DR — Buffett, Time, and Compounding

📈 Most of Warren Buffett’s net worth was created late in life—not because he improved, but because time magnified a large capital base

⏳ Compounding feels slow for decades, then accelerates rapidly—people often quit before the curve turns

💰 Savings rate builds the base; returns merely scale it

🎯 You don’t need Buffett-level skill—you need Buffett-level patience

📊 Average returns, applied consistently over time, often outperform constant optimization

Why One of Warren Buffett’s Greatest Advantages Was Time (Not Just Genius)

Warren Buffett is often considered the greatest investor of all time. But what’s far less discussed is when his wealth was actually created. The majority of Warren Buffett’s personal net worth—by most estimates about 95–99%—was accumulated after age 65, long after most people believe the wealth-building phase of life is over.

This article explains why time in the market is such a dominant force in wealth creation using the example of Buffett’s story. We’ll explore what regular investors can take away from his success and why savings rate often matters more than cleverness, why many people quit before compounding starts doing its real work, and how average returns applied patiently over decades can easily outperform nearly any attempt at chasing higher returns.

How Much of Warren Buffett’s Wealth Came After Age 65?

Before moving forward, one clarification matters. When people say Warren Buffett earned roughly 20% annual returns, they’re referring to Berkshire Hathaway’s compounded performance under his leadership, not his personal brokerage account. But since Buffett’s net worth is overwhelmingly tied to his ownership of Berkshire, the company’s long-term returns—averaging close to 20% annually since he took control in 1965—are still a reasonable proxy for his wealth creation.

If Warren Buffett had retired at age 65, he would still have been very successful, but many say he wouldn’t have gotten to his legendary status. For instance, according to Morgan Housel, author of The Psychology of Money, over 99% of Buffett’s personal net worth was created after age 65, driven by the continued compounding of his Berkshire Hathaway ownership. It’s been over 5 years since the book was published, so it’s likely much more than that figure today.

Similar conclusions have been independently highlighted by CNBC and Barron’s, all of whom show that Buffett’s wealth trajectory is overwhelmingly driven by long-term compounding rather than late-career outperformance.

What makes this insight so powerful is that Buffett didn’t suddenly become a better investor late in life. His investment acumen or any edge he might have had on others didn’t magically improve as he got older. It’s simply that his capital base became enormous; when you compound strong returns on a very large base for decades—as we’ll show today—the results can become staggering. We’re not saying time replaced skill, but that it simply magnified it.

For most investors, savings rate builds the base—returns simply scale it over time. Photo by Andrea Piacquadio on Pexels.

Was Warren Buffett’s Success Skill, Time — or Both?

It’s tempting to interpret this story as proof that time matters much more than talent. We don’t want to go that far here. It’s clear that Buffett wasn’t ordinary; he built and led a major company, accessed opportunities unavailable to most investors, and displayed exceptional discipline, skill, and temperament over many decades. We are reminded of his discipline by one of this famous quotes: “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who's been swimming naked”.

What Buffett’s story actually shows is that time amplifies whatever engine you’re running. For an investor with a poor savings rate who invests very little each month, having a 7% or a 12% return in the stock market won’t move the needle much. You need to have a meaningful capital base; for types like Buffett it can come from large salaries combined with solid savings rates; for the everyday investor it must come from high savings rates.

Next, we’re going to take a simple example to illustrate the enormous power of time.

A Simple Case Study: What Time and Compounding Really Do

To show the impact of time versus contributions, let’s consider a simple scenario, using the average market return Warren Buffett is thought to have enjoyed over his career (20%). But let’s apply it to normal household numbers:

Median household income: $80,000

Real stock market return: 20%

Savings rate assumed: 20% (this means $16,000 was saved and invested per year from a $80,000 salary).

Investing horizon considered: age 22 - 100

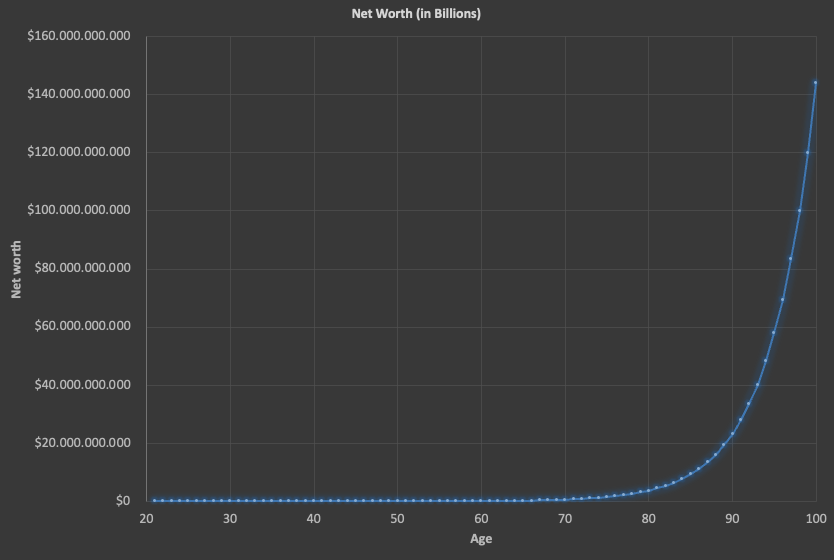

Below is what the compounding journey might look like…in billions.

First, a quick clarification. The graph is not wrong. This is what a strongly non-linear relationship looks like. In data science, you would never plot something like this—you’d use a logarithmic Y-axis instead so you can actually perceive net-worth values taking place from ages 22 to 75. They’re not actually zero—you just can’t see the early millions on such a large scale.

But I leave it as it is, because it strengthens our point. Observe that by age 70, in this example our net worth would be a whopping $606 million, yet still barely visible on the graph based on what is still to come.

In this case study, at age 80 we’d have $3.7 billion, and by age 95 (Buffett’s current age), we would have accumulated $57.8 billion. 99% of our net worth by then would have accrued after age 70.

Figure 1: Net worth over time, assuming $16,000 annual savings and investments and 20% average return over a 78 year period (age 22-100). Normally, you’d plot this type of graphs on a log-scale so you can actually see the net worth from ages 22-70; I left it like this because it helps understand how much the percentage of net worth comes from “time in the market” and from the last few years. This is exactly the trajectory Buffett is on.

So, in this simple exercise we’ve learned two things: first, that anyone would have become a billionaire with a normal salary had they achieved a 20% average return and stayed invested for over six decades; second, we confirmed that, indeed, the overwhelming majority of Buffett’s net worth came after age 65. Had he retired at 65 and simply stayed invested in index funds, he would almost certainly still be a billionaire—but probably not a famous one. This model assumes constant returns and uninterrupted investing. Real life is messier—but the direction of the effect remains the same.

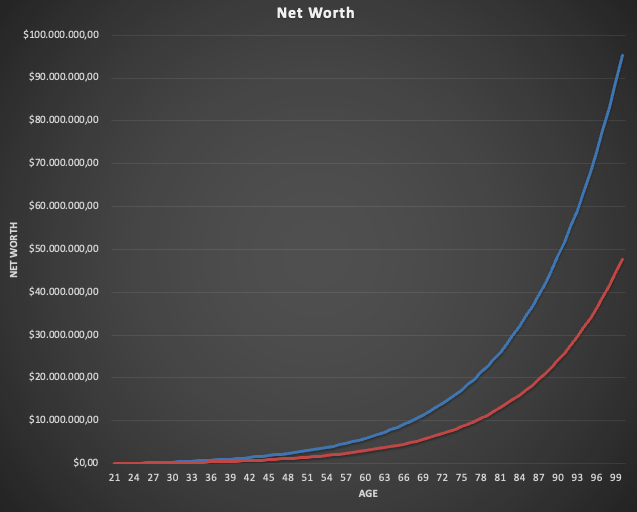

Next, let’s forget about the 20% return, and come back down to Earth. Buffett’s returns are exceptional, but to understand what’s realistic for most investors, we need to adjust the assumptions. Most retail investors can expect a healthy 7% return or so by investing in low-cost, internationally-diversified index funds over long periods of time. What would this same example look like—all else equal? Will we become billionaires like Buffett, perhaps in our late 90s?

As observed in Figure 2 (and hopefully as you’d expect!), none of us will reach billionaire status on normal salaries and average returns—whether we implement a 20% savings rate (in red) or even a 40% savings rate (in blue). The incredible power of compounding is still there though—reaching $12M and $24M by age 80, respectively, depending on your savings rate, and far more beyond. If you did continue to live well beyond your investment returns, the compounding would still take you to much higher numbers late in retirement.

Figure 2: Net worth over time, assuming $16,000 annual savings and investments (20% savings rate; red) and $32,000 (40% savings rate; blue), and assuming a 7% real return on investment. Nobody will reach billionaire status, but the non-linear trajectory could push you in the tens of millions if you worked until Buffett’s age (or lived strongly under your portfolio means in retirement)

Why Most People Never Experience the “Buffett Curve”

If compounding is so powerful, why don’t more people experience anything remotely like the trajectories shown above? The answer usually has very little to do with math and a lot to do with psychology.

The early decades of compounding are typically very unrewarding. Your investment contributions dominate returns, progress feels linear, and the exponential nature of growth is pretty much invisible.

From my own experience, this was the phase that felt the hardest so far on our road to Financial Independence. Getting to the first $100,000 is frustratingly slow and required far more effort than I had anticipated. Saving felt heavy, progress pretty much invisible, and it often seemed like the market wasn’t doing much for us. What surprised me later was how much these dynamics changed once a sufficient base was in place. The next milestones came noticeably faster—not because we became better investors, but because compounding finally had something meaningful to work with.

In the short term, this can create a dangerous mismatch between perceived effort and feedback. We’re working hard, saving diligently, investing consistently, and staying the course through market volatility—yet the results don’t seem to reflect the effort. It’s during this phase that many abandon their strategy, either by stopping contributions, chasing higher returns (often unsuccessfully), or retreating to cash after downturns.

This is where Buffett’s example is so powerful—his temperament matches his skill. He didn’t just identify good buying opportunities; he stayed invested through long stretches of “boredom”, underperformance, and volatility. Many investors fail not because they chose the wrong asset, but because they couldn’t tolerate the emotional discomfort of slow, early progress. Compounding only rewards those who stay in the game long enough.

There’s also a cognitive trap at play here. Humans are great at understanding linear cause and effect, but terrible at intuitively grasping non-linear dynamics such as exponential growth trajectories (explained in Kahneman’s famous Thinking, Fast and Slow). We simply underestimate how powerful time will be later, while overestimating how much optimization matters early on. This leads to endless tinkering—portfolio changes, strategy switches, or attempts to time the market.

These changes make us feel productive, but in reality we’re more often just sabotaging the future compounding we’re trying to harness.

Compounding works quietly for decades—like an old oak, its strength comes from time, not speed. Photo by Johannes Plenio on Pexels.

Bringing It All Together: What Buffett’s Story Actually Teaches Us

Buffett’s story is often told as a tale of a genius. But it’s also a case study in patience, consistency, and letting time do its thing. His extraordinary wealth ($140 billion as of early 2026) wasn’t created by some late-life breakthrough, a secret strategy, or an increase in intelligence. In fact, his returns over the last 20 years have underperformed the S&P 500. And yet he still created the vast majority of his net worth in recent years.

For regular investors, the lesson is certainly not to chase 20% returns. Again, Buffett underperformed the S&P 500 over the last two decades. Buffett critics often like to highlight this underperformance, but that actually reinforces the point of today’s article: even average or slightly below-average returns, when applied to enormous capital over long periods, still dominate outcomes.

It’s neither realistic nor necessary to chase 20% returns. The key takeaway is far more simple and actionable: save aggressively, invest consistently, keep investment costs low, and stay invested for as long as possible. High savings rates build the base, while reasonable returns applied patiently over time do the rest.

Buffett’s trajectory reminds us that wealth creation is not evenly distributed across time and that financial success is less about brilliance and more about endurance, especially for retail investors. Time in the market isn’t just important—it tends to dominate everything else. And while few people will ever replicate Buffett’s returns, many of us could choose to replicate the behaviors that made his success possible.

Want to go deeper?

👉 Use our Financial Independence Calculator to see how time and savings rate shape your net worth and retirement trajectory

👉 Want to understand how to retire in your mid-40s? Check out what savings rate will get you there depending on age and current portfolio size.

👉 Subscribe to The Good Life Journey (free tools & monthly newsletter, unsubscribe anytime)

💬 What surprised you most about when Buffett’s wealth was actually created? Does this change how you think about skill, patience, and time in your own investing journey?

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

Check out other recent articles

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Most estimates suggest that over 90–95% of Warren Buffett’s net worth was created after age 65. This is largely due to decades of compounding acting on a massive capital base, not because his investment skill suddenly improved late in life.

-

While exact figures vary by estimate date, Buffett’s net worth increased by tens of billions of dollars after age 65, with the vast majority of his current ~$140B fortune accumulated in his later decades.

-

The ~20% figure refers to Berkshire Hathaway’s compounded returns since 1965, not Buffett’s personal brokerage account. Annual returns varied widely, but the long-term average is close to 20%.

-

Yes—he would likely still be a billionaire. However, without the final decades of compounding, he would not have reached the scale or legendary status he holds today.

-

Both matter. Buffett had exceptional discipline and skill, but time amplified those traits. Skill without time rarely creates extreme wealth; time without discipline rarely works either.

-

Not in returns, but in behavior. High savings rates, low costs, diversification, and staying invested for decades capture much of the same compounding effect at a smaller scale.

-

Because compounding is exponential. Early growth feels slow, but once the capital base is large enough, returns dominate contributions and growth accelerates dramatically.

-

Early on, yes. A higher savings rate builds the capital base faster, which allows compounding to matter later. Returns matter most once meaningful capital is deployed.

-

Because many stop investing, change strategies, or panic during downturns before compounding has time to work. Psychology, not math, is usually the limiting factor.

-

Extreme wealth is rarely about brilliance alone. Patience, consistency, and time in the market dominate everything else.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>