Understanding the “One-More-Year” Syndrome in early retirees

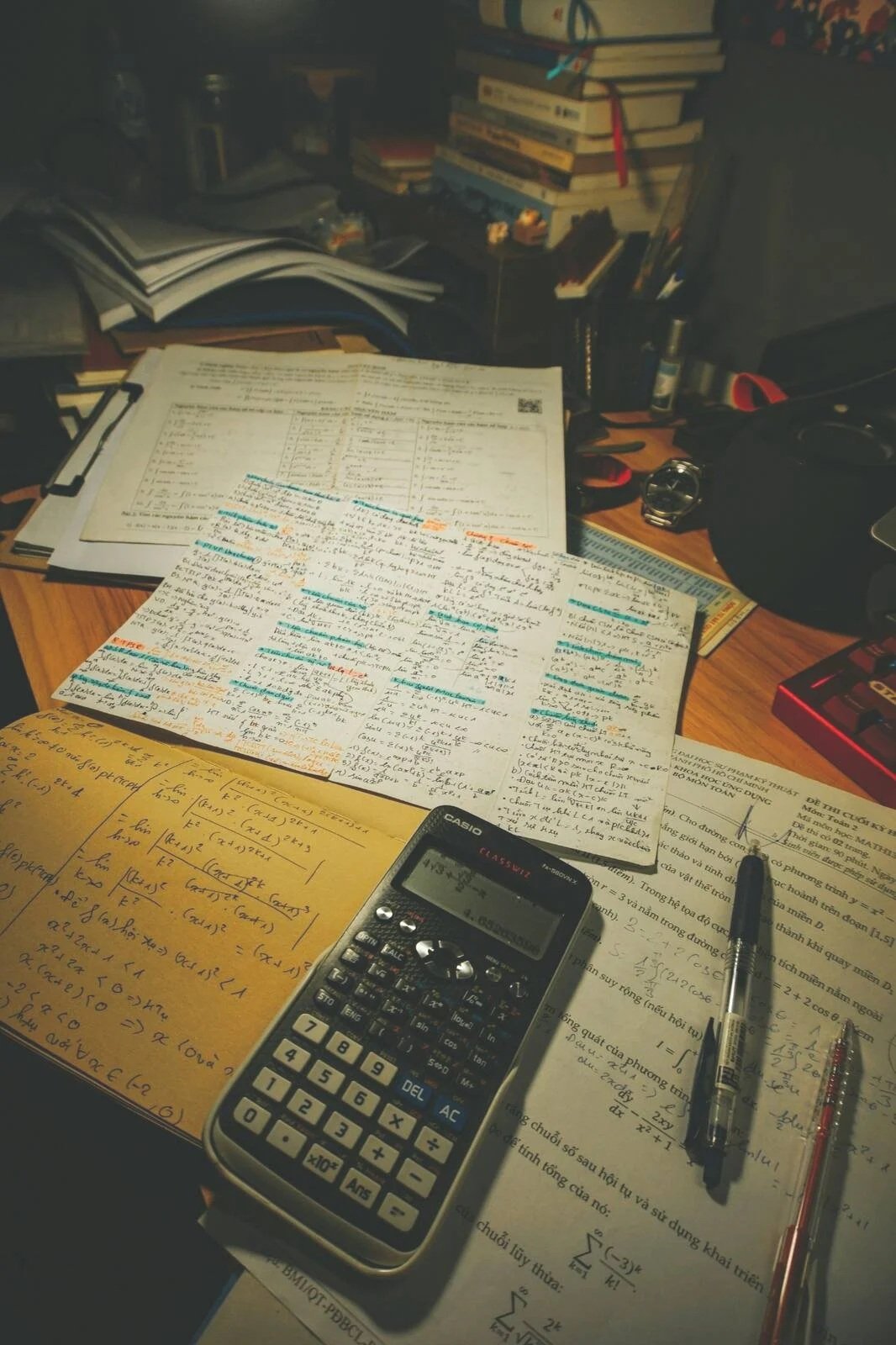

Many workers reach Financial Independence and retire early from their main career, yet find themselves unable to do so for non-financial reasons. Photo by Israel Andrade on Unsplash.

Reading time: 9 minutes

🚀 TL;DR — The Real Reasons People Delay early retirement (and How to Break Free)

🧠 Fear beats math: Most FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) followers delay retirement because loss aversion, uncertainty, and identity concerns overpower the math.

📈 Compounding creates FOMO: Near your Financial Independence number, each extra year can add six figures to your portfolio—making it emotionally harder to walk away, even when it comes at the expense of your health.

❤️ Time > money: The real risk isn’t running out of money—it’s running out of healthy, active years to enjoy freedom.

🛠️ You overcome OMY syndrome through flexibility: Guardrails, semi-retirement, part-time work, and dynamic spending unlock freedom sooner than perfectionism ever will.

🧭 Bottom line: You don’t need certainty to retire—you need enough confidence, adaptability, and a life you’re excited to step into, not just away from.

Why You Can’t Retire: Understanding the One-More-Year Syndrome

If you’ve spent any time in online FI communities, you’ve seen it: people who are already financially independent, who have reached their long-awaited FI number, yet can’t bring themselves to retire. This is the classic “one-more-year syndrome”—often a mix of financial FOMO, psychological fear, uncertainty, identity loss, and the intoxicating growth of a rapidly compounding portfolio.

In this article, we break down what the one-more-year (OMY) syndrome is, why it happens, how to recognize it in yourself, how the math of late-stage compounding feeds the hesitation, and how to decide whether you should retire now or wait one more year. By the end, you’ll have a clearer understanding of the fears, incentives, and hidden trade-offs driving OMY syndrome—including the real cost to your time and health.

Understanding the OMY syndrome in retirement planning is crucial because it often hides not financial weakness, but emotional hesitation.

Some people find themselves working much longer to reach higher portfolios than they had originally aimed for. Often the perception of “easy money” keeps them in the game longer than anticipated. Photo by Alexander Grey on Unsplash.

The Compounding Trap: Why Your Portfolio Grows Fastest Right Before Retirement

People often underestimate how emotionally powerful the later-stages of the Financial Independence journey are—especially when they hit their FI number, i.e., the “Crossover Point”, during a bull market. You can have a fully funded FI portfolio, a conservative bond tent and withdrawal rate, and years of careful planning behind you, and yet the temptation to “stay just one more year” becomes intense. Why does this happen exactly?

Firstly, because at the exact moment your portfolio is the largest it has ever been, the markets starts “handing out” its biggest gains. Imagine you reached your $1.5M Financial Independence portfolio, capable of granting $70,000 per year in retirement spending as per the 4.7% rule of thumb.

This also means that if the market moves up 7% (in real terms) in the following year, that’s $105,000 extra per year added to your portfolio (without including your annual savings from your salary!) That’s an incredible amount of money; after all, you recognize that it took you years to save and invest this amount in the earlier stages of your career, and now it all seems too easy.

As shown in Figure 1, after “only” three more years of OMY syndrome, your portfolio could easily jump to a $2M portfolio—or much, much more if you are in the middle of a bull market. Your annual retirement withdrawals could go from $70,000 per year to at least $95,000, a substantial jump.

Figure 1: Screenshot of our Financial Independence Calculator—free for email subscribers. As observed, a $1.5M portfolio at age 43 might increase—after just three more years of one-more-year syndrome to a $2M portfolio. Your annual retirement withdrawals would go from $70,000 per year to $95,000, a substantial jump. This scenario assumes average real returns of 7%.

In the mind of someone already stressed or exhausted by work, this creates a paradox: walking away now feels like you’re walking away from the “easiest” money of your life—in the example, around $500,000 in three years or $1M after 6 years. Of course, the exact amount also depends on your savings rate and the level of your salary, but you get it—the amounts are substantial.

This financial FOMO also becomes potent because many FIRE folks tend to hold strict interpretations of what withdrawal rates should look like. A specific spreadsheet may suggest a 4% safe withdrawal rate (SWR), so they anchor to it. Or a model says they only have 100% certainty in the modeled scenarios if they adopt a 3.3% SWR. Ultimately, they convince themselves they cannot leave until everything is absolutely perfect.

Of course, often they ignore that retirees in the real world can be flexible and adjust spending during severe market downturns, and that research suggests expenses will go down as they age—we simply don’t spend the same amount in our 40s-60s as we do in our 70-90s.

By ignoring flexibility, they treat retirement math as static, when in reality humans are highly adaptable and we can use dynamic spending strategies. Most FIRE households have tons of levers available—think temporary geo-arbitrage, cutting discretionary categories, earning part-time income, or skipping a car replacement—that make running out of money far less likely than the fearful mind suggests. Fear thrives in rigidity—and rigid financial thinking reinforces the one-more-year loop.

And yes, markets can fall right after you retire—but that risk exists no matter when you leave, and dynamic spending rules and bond tents are designed precisely for this scenario.

Another trap is the illusion of perfect timing, when in reality it will always feel like it’s not the right time to pull the trigger. If you hit your FI number during a market boom (think 10-30% annual return), quitting the race feels irresponsible—you’re leaving so much money on the table. In contrast, if they hit FI during a downturn or the market is going sideways, it equally feels dangerous to leave when things look so uncertain. And so, the perfect moment never arrives.

The risk is that what seems like a rational desire to “optimize” or take advantage can turn into a quiet trap where time, relationships, and health keep slipping away. Yes, the portfolio is compounding—but so is the cost of waiting.

Money is only half the equation. The deeper forces keeping people in the OMY loop are psychological.

Often, analytical-minded FIRE individuals over-emphasize perfection over flexibility. They try to pursue the most optimal early-retirement strategy to eliminate all sources of uncertainty—forgetting that uncertainty is a feature of life. Sometimes, an overly-conservative plan comes at the cost of time and health. Photo by Campaign Creators on Unsplash.

Fear, Uncertainty, and Loss Aversion: The Psychology Behind Delaying Retirement

Loss aversion is one of the strongest psychological forces behind the one-more-year syndrome. Even when someone is FI, the fear of running out of money can dominate the fear of wasting years of life. Behavioral research shows that humans feel losses more intensely than gains, so the idea of a shrinking portfolio creates more emotional weight than the promise of more free time.

In addition, many FIRE folks grew up with scarcity mindsets—childhood financial instability, modest beginnings, or parents who constantly worried about money. Often, these financial worries can seamlessly transfer to the next generation, even when objectively the situation warrants no worry. This is one of the reasons it’s so difficult for many people to retire early, even when the math says they can. Those scripts and childhood stories don’t magically disappear when a FI calculator says you’ve made it. As Morgan Housel reminds us, money is more emotional than it is rational.

Uncertainty often amplifies this fear, especially uncertainty around healthcare costs, job markets, and longevity. US readers in particular will agree here, where healthcare costs are both high and unpredictable. Even high-income earners in the FIRE space admit they would retire earlier if they felt more clarity around their healthcare situation.

Of course, there are as many fears as there people. Other common fears are recessions, sequence-of-return risk (SORR), inflation, technological breakthroughs, or geopolitical instability. Many of these global uncertainties naturally feel completely out of one’s control. The irony is that trying to eliminate all uncertainty before retiring does guarantee one thing—that you’ll never retire.

The desire for 100% safety becomes its own form of risk. It creates an illusion that working more years equals more control, when in reality life is defined by uncertainty. One of the few things that becomes more predictable with age is declining physical resilience.The healthier approach to uncertainty is to embrace a mindset of resilience and antifragility.

This leads to the emotional paradox of the OMY syndrome: people fear running out of money more than they fear running out of time. Yet the math on time is far more unforgiving. The average healthy retirement years in the US is 8.1 years for men and 9.6 for women—numbers that should give pause to anyone considering another 5-10 years in a high-stress job.

The body’s health does not compound like an index fund—it declines. Stress, poor sleep and diet, and a lack of exercise accelerate it. Many FIRE followers in their 40s or 50s are already feeling the warning signs in the form of burnout, sleep issues, weight gain, or constant anxiety—nearly everyone I know experiences the Sunday scaries. In my view, the greatest loss aversion of all should be losing one’s health. Unfortunately, since that loss tends to be gradual and abstract, people often discount this risk until it’s too late.

Work Identity, Status, and the Fear of Retiring Early

Work identity is another massive driver of the one-more-year syndrome—especially for high achievers in prestige-driven fields (think doctors, lawyers, researchers, engineers, consultants). Walking away from high-status professions and fancy job titles is difficult for most. The transition period can be difficult to manage, because it often involves partially reinventing oneself and reflecting on how we tie our identity to a certain social class.

Having recently left my research and consulting career, I’m very aware of the mixed emotions you experience when transitioning away from something you had tied your identity around for such a long time. It’s complicated. Indeed, writing regularly for The Good Life Journey has become part of rebuilding that identity—reminding me that life outside a traditional career can still be meaningful, creative, and more aligned with your values and lifestyle preferences.

Many people on the verge of FI feel like they could lose relevance, community, or validation. This is why some people who could retire at 45 struggle to do so and stay another decade—they’re not being held back by the math, but by identity and, perhaps, a lack of imagination of the millions of endeavours they could engage in in early retirement.

Of course, some people delay retirement simply because they genuinely enjoy their work. That’s a very valid reason for staying in your job after reaching Financial Independence—but in those cases, it’s worth distinguishing joy from habit and purpose from fear.

This becomes especially problematic in workplaces where social ties are mistaken for real friendships, where belonging depends on professional contributions, or where someone’s self-worth is anchored in productivity.

Status anxiety also shows up as fear of judgement. What will others think if I stop my career this young? Even when someone has mathematically outgrown the need to work, the (perceived) social pressure to appear “successful” persists. Some worry colleagues, friends, or family will see them as lazy, or think they’re being irresponsible.

Others fear losing the status that came from a prestigious email signature—“Michael Brown, PhD, Senior Research Consultant at XXXX”. Perhaps it’s a big and impressive project, or a team that depends on them. We are social animals and social loss can feel dangerous—even if it’s within the artificial and feeble social structures set up by your employer.

This makes staying “one more year” feel safer. But think back on the hundreds of colleagues you’ve interacted with over the last decade/s in previous jobs (don’t count your current one). How many of them truly remain your friends?

Finally, there’s also the deeper fear of figuring out what will fill the space once work disappears. For some, who haven’t lived for work and have cultivated a myriad of interests and hobbies, this is certainly not a problem. But many others on the verge of FI discover that they haven’t built enough hobbies, friendships, or a sense of meaning beyond productivity.

Retirement can become a blank page—exciting for some and frightening for others. Without a pre-build identity for life after work, pulling the trigger feels like stepping off a cliff. This is why rehearsing retirement before pulling the trigger—through mini-retirements, sabbaticals, or long vacations is so powerful. It allows people to experience an upcoming reality: the world doesn’t have to collapse when they step away. In fact, it should expand.

Even if you manage the identity shift, another trap often appears—the desire to mathematically optimize your retirement plan.

Many careers become a strong part of our identity. It’s hard to step away if you’ve over-emphasized work over other dimensions of life. Photo by Accuray on Unsplash.

Spreadsheet Paralysis and the Moving Goalpost Problem in FIRE

It’s not a secret that Financial Independence tends to attract analytical thinkers—the same type of thinkers that often fall into spreadsheet paralysis. They run model after model, obsess over market conditions and historical performance, optimize every cell, and constantly tweak projected withdrawal rates.

But spreadsheets tend to model financial outcomes, not human behavior, flexibility, creativity, or changing priorities. When someones tries to reduce a 30-to-50-year life to a single safe-withdrawal number, they tend to get stuck or shoot for overly-conservative goals.

Again, perfect can be the enemy of good—the quest for perfection brings anxiety rather than clarity, and the spreadsheet becomes a tool for avoiding some of the real emotional questions: How much is enough? What would I actually do with my time? What am I afraid of losing?

Perfectionism compounds the OMY syndrome: people convince themselves they must have a flawless plan before quitting. This often leads to hyper-optimization and to changing the goal posts over time: “I’ll retire when I hit 1.5M” turns into 1.7M turns into $2M. Or another classic: “I’ll wait until the markets stabilize”, until inflation cools, the next election, or the next promotion.

The goalpost often moves not because the plan is flawed, but because underlying fears remain unaddressed. And perfectionism disguises fear behind rational-sounding excuses. Ironically, many of these people may advise others to retire early and trust themselves. But internal standards are usually harsher—fear dresses up as responsibility, and responsibility becomes the main reason to wait.

Underneath it all is thinking in absolute terms—the belief that retirement must be permanent and rigid—when in reality, it can be flexible. Semi-retirement, Barista FIRE, part-time or bridge jobs are not failures to the plan, but can be tools to make it work. A person who hits Lean FIRE in her early 40s doesn’t need to burnout another decade to reach Fat FIRE. She can also shift careers, reduce hours substantially, or work in lower-paying passion projects that allow her portfolio to compound in the background.

For many, a hybrid approach offers the best of both worlds: meaningful work and meaningful time. Perfectionism says we must choose one—but reality tends to be much more flexible.

Life is characterized by uncertainty and taking a step into the unknown is not easy. Adopting a mindset of flexibility, resilience, and antifragility can help you make bolder moves. Photo by Andres Molina on Unsplash

Should You Retire Now or Wait One More Year? A Framework for Deciding “Enough”

Many FIRE folks forget the Financial Independence is not just a number—it’s the ability to reclaim time. Yet they act as if the number is sacred and the time expendable. The most important question in the OMY syndrome is simple: Which risk matters more—running out of money or running out of time?

Most people overestimate the first and underestimate the second. While portfolios can recover from market dips, lost years with children, lost years of mobility, and lost years of youth can’t be reclaimed. Healthspan research shows that physical resilience declines sharply in midlife. Every extra year in a stressful job chips away at your future freedom more than you realize.

A better approach is to not chase perfection and certainty, but to adopt a resilient and antifragile mindset. Instead of obsessing over a single, fixed withdrawal rate, people can focus on designing retirement spending guardrails, lifestyle flexibility, optionality, and contingency plans. Spending can be adjusted, travel can be paused during market downturns. Even a temporary small income stream can extend portfolio longevity dramatically.

And, again, many retirees find they naturally spend less in their 70s and 80s—the famous Retirement Spending Smile. If you’ve followed the 4% rule of thumb and are willing to be a bit flexible in spending, in all likelihood you’ll end up with more money than you started your early retirement with.

Uncertainty in finances—and in life—will never disappear, but your ability to navigate it may actually grow once you’re not chronically exhausted by full-time work in a job you dislike. The goal here isn’t certainty, but optionality and adaptability. This flexible mindset is one of the most effective ways to overcome the one-more-year syndrome, because it reduces the pressure of needing a perfectly predictable retirement.

Ultimately, the solution to the OMY syndrome is not just mathematical, but psychological. We need to build a vision of life after work that excites them more than their fear of the unknown. We need to develop interests, nurture friendships, and cultivate routines that make stepping away feel like moving towards something, not away from something.

We need to release the inherited narratives around scarcity, productivity, worthiness, and identity, and trust that our future self will handle whatever uncertainty is thrown to us next. When the fear of wasting life becomes stronger than the fear of losing money or facing uncertainty, the OMY syndrome loosens its grip—and the answer you’ve been circling quietly becomes obvious.

💬 If you had to choose today: would you take one more year of income—or one more year of health, freedom, and energy? How do you weigh time versus money in your FI journey? Share your thoughts in the comments below.

👉 Want to understand how to retire in your mid-40s? Check out what savings rate will get you there depending on age and current portfolio size.

👉 Looking to retire a decade or more early? Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free for email subscribers) to plug in your numbers and see how soon you could go into retirement.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimers: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The one-more-year syndrome is when someone who is financially independent keeps delaying retirement, convincing themselves they need “just one more year” of income. It’s driven by fear, loss aversion, financial FOMO, and identity issues. Even people with large portfolios struggle with this because the emotional side of retirement often outweighs the math.

-

Retiring early requires giving up identity, routine, status, and predictable income. Many FI followers underestimate the psychological transition and overestimate financial danger. Fear of market uncertainty, healthcare costs, and losing purpose often keeps people working longer than necessary.

-

If you’re financially independent, the decision hinges on two risks: running out of money versus running out of time and health. Waiting one more year increases your portfolio, but it also reduces your healthy years of life. Use spending guardrails, flexibility, and part-time options to assess your comfort with leaving.

-

Signs include constantly updating your FI number upward, saying “I’ll quit once the market stabilizes,” or feeling anxious when imagining life without work. If the math says you’re FI but the emotions say you’re not ready, you’re likely facing OMY syndrome.

-

Build a realistic retirement identity, rehearse retirement with sabbaticals or mini-retirements, use guardrail spending rules, and explore part-time or bridge jobs. Most importantly, redefine “enough” and accept that uncertainty will always remain. Flexibility protects you more than waiting endlessly.

-

Loss aversion, scarcity mindsets, healthcare worries, and identity loss are major drivers. High earners also struggle because late-stage compounding makes the final years feel incredibly lucrative. The fear isn’t irrational—it just needs to be understood and balanced.

-

Your portfolio grows fastest when it’s largest. A 7% gain on $1.5M feels very different from a 7% gain on $300k. This “easy money” creates powerful FOMO, making people feel like retiring now means walking away from massive gains.

-

Healthy retirement years are limited—often 8–10 years for the average American. Stressful work erodes healthspan faster than people expect. Many regret trading peak health years for small increases in their portfolio.

-

Yes. Semi-retirement or part-time work gives the psychological security of income with the lifestyle freedom of FIRE. It’s one of the most effective tools for transitioning away from full-time work without feeling financial or emotional shock.

-

Use withdrawal guardrails (e.g., Guyton-Klinger), test your budget, track real spending, and model scenarios. Confidence comes from understanding flexibility—not from hitting one “perfect” number. You don’t need certainty; you need resilience.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,103);

});

</script>