20 Criticisms of the FIRE Movement (And Which Ones Are Valid)

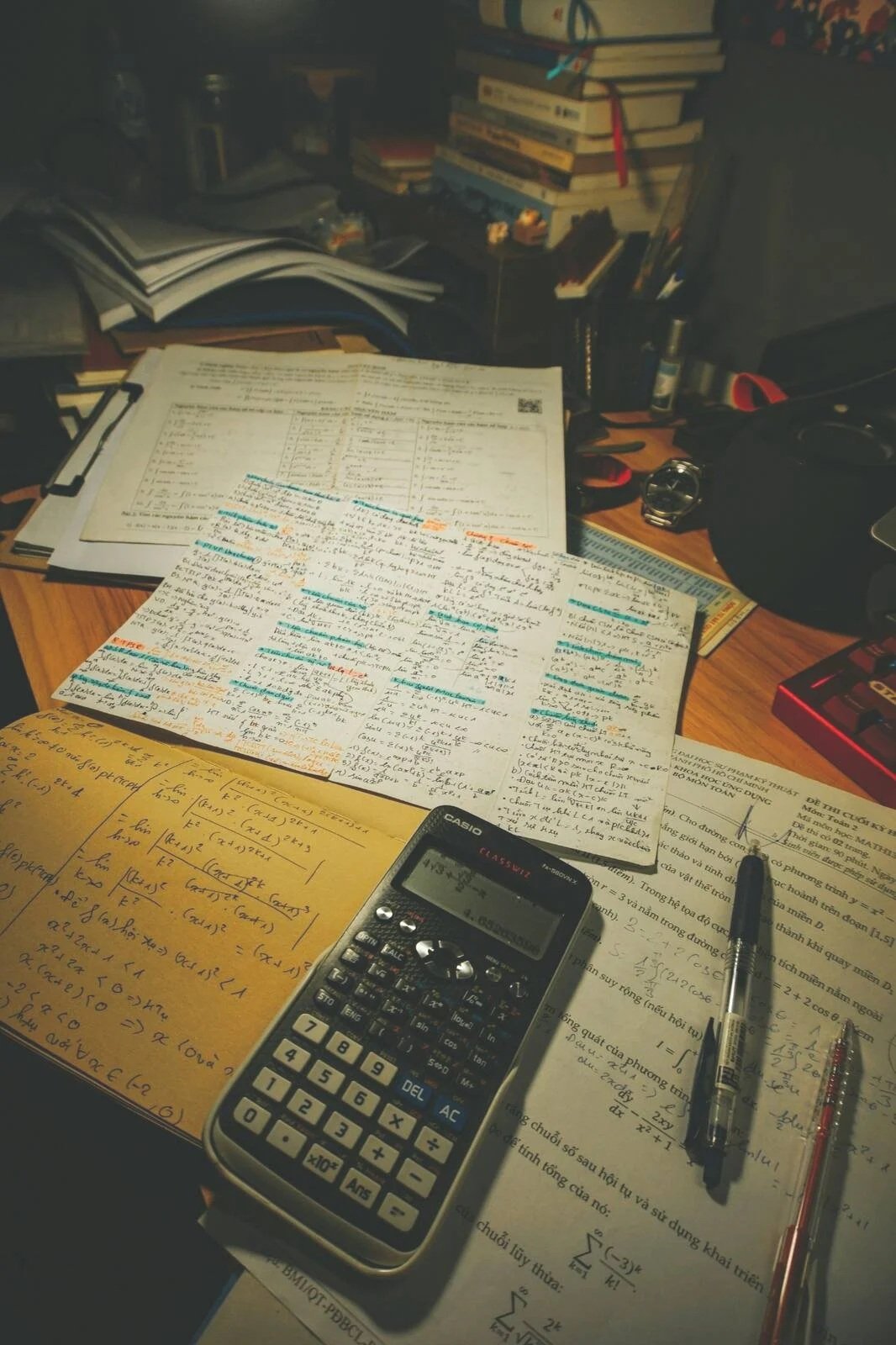

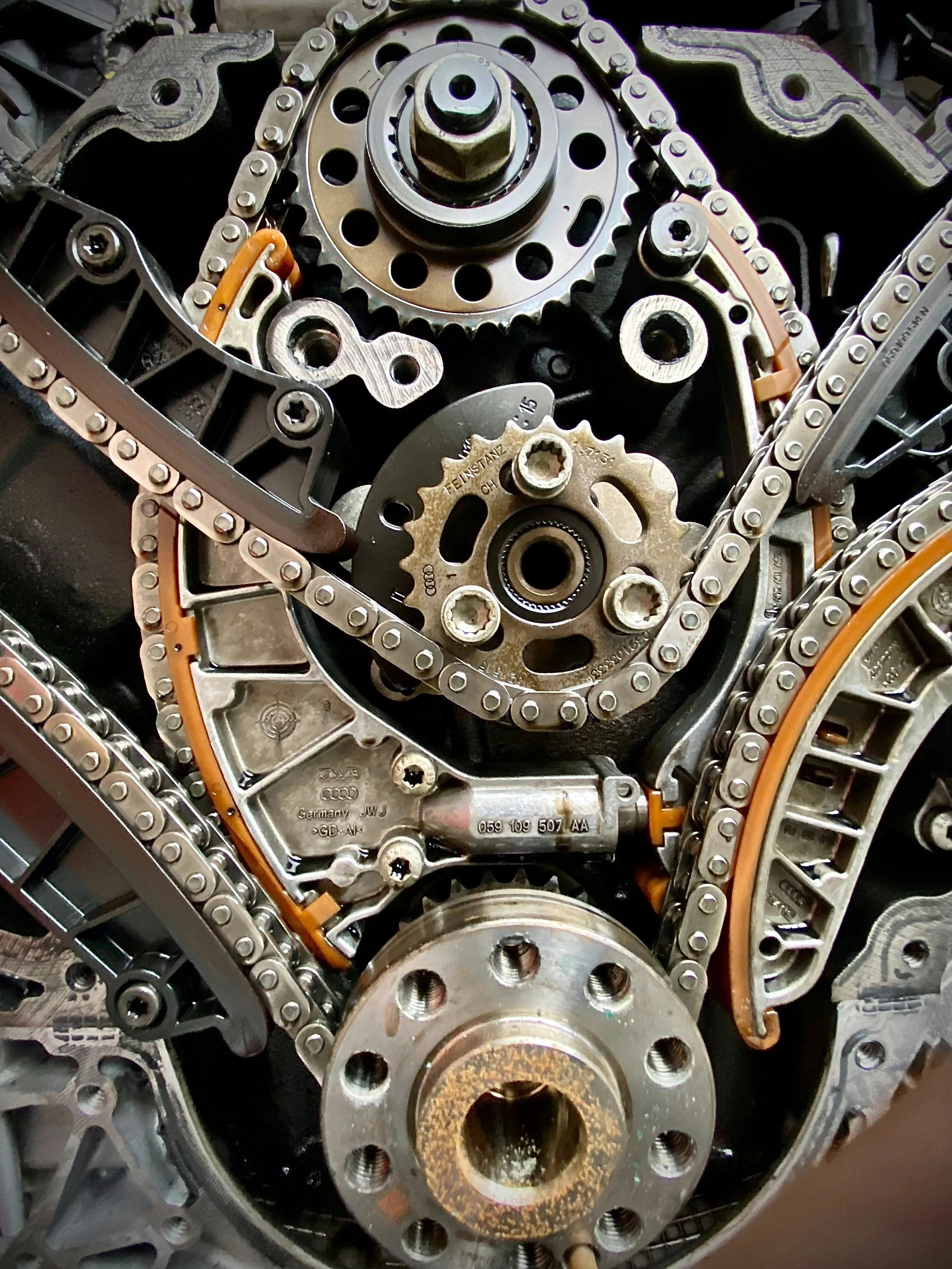

Some FIRE critiques often center on the investment engine behind it—markets, assumptions, and long-term uncertainty. Photo by Jakub Żerdzicki on Unsplash.

Reading time: 7 minutes

Quick answer:

Depending on how it’s implemented, pursuing FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) can present real drawbacks—especially around purpose, social connection, and, for some, the psychological risks of extreme frugality. But many of these challenges are manageable if the focus shifts toward achieving Financial Independence for flexibility and optionality, rather than a rigid goal of “retiring at 35.” It also helps to plan life after work—purpose, people, and daily structure—as carefully as the financial side.

What you’ll get from this article

✔ 20 common FIRE movement criticisms (economic, psychological, ethical, practical)

✔ Counterarguments for each—what’s valid vs what’s overstated

✔ The two drawbacks I think matter most (purpose + social structure)

✔ Who FIRE is a poor fit for—and why

✔ How to pursue FI without burnout, deprivation, or identity traps

TL;DR — FIRE movement pros & cons 🔥🧭

TL;DR — FIRE movement pros & cons 🔥🧭

💸 The math matters, but the human risks (purpose + people) matter more

🧠 The “FIRE finish line” feeling fades; autonomy doesn’t

🧯 Extreme frugality can backfire—flexible FI is usually healthier

🌍 Ethical investing is complex; individual impact is often bigger via consumption and policy

🛠️ FIRE is a tool: it can narrow life if rigid, or expand it if intentional

⏳ FI is not binary—freedom grows gradually long before early retirement

👥 Retiring to purpose and community matters more than retiring early

📉 Perfect forecasts are impossible—flexibility and buffers matter more than precision

🏛️ FIRE doesn’t create inequality or insecurity, but responds to a world where individuals must manage more risk themselves

20 Criticisms of the FIRE Movement (and Why Financial Independence Still Matters)

The FIRE movement (Financial Independence, Retire Early) has changed how millions of people across the globe think about money, work, and freedom. At its core, it asks a simple but very radical question: What if work were optional decades ahead of traditional retirement?

For many, this idea empowers them towards different forms of more intentional living. But for many others, the whole idea of early Financial Independence feels unrealistic, privileged, or somehow risky. There are tons of articles out there criticizing the FIRE concept—whether its focus on extreme frugality, market uncertainty, or the fear that early retirement from a traditional career could lead to boredom and loss of purpose.

Many of these criticisms tend to blur an important distinction: Financial Independence (FI) is not the same as early retirement (ER). In practice, a large share of people pursuing FIRE don’t quit all productive activity in their 30s or 40s, but are trying to gain:

flexibility over how they spend their time—what their day-to-day looks like

the ability to choose more meaningful or lower-stress work that is often unpaid or not paid very well

freedom to make life decisions that aren’t driven only by money

protection against recurrent layoffs or against burnout in high-stress work environments

Seen this way, the debate becomes much more nuanced, where philosophical questions arise about the importance of autonomy and the role of work and employment in leading a good life.

From my experience, the biggest surprise has been how much sense of freedom has arrived before reaching the FI finish line. Being 7–8 years into the path to FI already has made me more willing to take career risks, say no to low-value work, and prioritize time with family.

In this article, I’ll walk through 20 of the most common criticisms I’ve seen of the FIRE movement—along with counterarguments and/or practical ways to avoid some common pitfalls. I’ll cover the big buckets people usually worry about: whether FIRE is realistic on normal incomes, the risks of relying too strongly on stock markets, the psychological downsides of early retirement, and some ethical critiques around investing and inequality.

I’m not trying to defend FIRE blindly here. Some of the criticism I find valid. The point is to assess what holds up and what doesn’t, and how to pursue Financial Independence in a way that increases freedom without creating new problems for us.

Long retirements magnify uncertainty—future healthcare, inflation, and policy shifts can change any financial plan. Photo by Moritz Böing on Pexels.

A) Structural & Economic Criticisms of FIRE

1. FIRE often requires a high income or structural privilege

A very common argument is that FIRE is only realistic for high earners. Many households struggle to cover basic living costs, making the implementation of the aggressive savings rates required for pursuing FI feel close to impossible. This argument may feel validated at first glance in online FIRE forums, where you do see a disproportionate number of folks coming from tech, finance, or other well-paid industries. The country you live in, your family obligations, economic inequality, and other factors all shape what is feasible, meaning FIRE is presented by critics as inaccessible or even exclusionary.

Counterarguments:

Firstly, Financial Independence exists on a very wide spectrum, rather than as an all-or-nothing outcome. While it’s true that it will be more difficult to achieve FIRE in your 30s or 40s on a low salary, you can still retire 10-15 years earlier by implementing moderate savings of around 15-20%.

This is, in itself, a huge accomplishment; but more importantly, accumulating investments over several decades will create a psychological sense of freedom long before reaching formal retirement. While not every one can reach extreme early retirement, most people can still retire in their early 50s, while improving resilience and optionality throughout their career.

Secondly, we should not forget that everyone has agency over changing the income trajectory of their lives. Online FIRE forums are also flooded with stories of normal salary households retiring in their 40s.

Finally, the perception that FIRE is dominated by high earners may partly reflect visibility bias rather than reality. FI online forums and media coverage tend to amplify extreme success stories because they attract attention, while quieter paths to FI on moderate incomes remain more under the radar. But as observed in Lean FIRE forums, there are thousands of examples of FI pursuits on leaner budgets.

2. Market returns may not sustain very long retirements

Retiring in your 30s or 40s means depending on investment markets for very long periods, sometimes 40-to-60 years—far longer than traditional retirement models assume. Sequence-of-returns risk, high valuations, or prolonged downturns could threaten portfolio sustainability, especially for early retirees.

Counterargument:

FIRE strategies typically include guardrails for this, either in the form of conservative withdrawal rates, diversified portfolios, bond tents, flexible spending in retirement, or in the worst case the possibility of part-time income if needed.

Moreover, those with the discipline of having accumulated a FI portfolio early in life often have the mindset and skills that reduce the chance of failure and increase the likelihood that they will find a way to adapt, even during unusually turbulent times. While you can’t fully eliminate uncertainty from life, preparation and the ability to stay flexible meaningfully lowers the risk.

3. Inflation, healthcare, and unknown future costs are unpredictable

Long time horizons can amplify forecasting errors. Healthcare systems can change over time, inflation varies, and personal needs can change too. Even small miscalculations could compound against you over decades, making any precise FIRE planning difficult.

Counterargument:

The unpredictable nature of healthcare, inflation, and longevity is one of the most serious challenges to long retirement timelines—and FIRE does not eliminate some of the risks. But in many ways, pursuing FI earlier can improve the ability to respond to uncertainty.

Someone who reaches FI in their 40s still has time, health, and earning capacity to adapt if conditions change radically, whereas traditional retirees often face the same risks but with far fewer options. FIRE planning therefore shifts the goal from perfect prediction to resilience: building flexible spending, diversified assets, and the ability to adjust course when the future differs from the plan.

4. Government policy and tax rules may change

Retirement accounts, capital-gains taxes, and social benefits are shaped by political decision, which can change over time. Plans built on current regulations are risky and may not hold decades from now.

Counterargument:

Governments do change the rules, and any multi-decade (think 40-60 years) plan must accept that reality. Yet FIRE is often portrayed as unusually vulnerable to policy shifts when the opposite may be true. Traditional retirement depends more heavily on pensions, social security systems, or specific tax treatments that individuals cannot control.

While legislation can affect timelines or taxes, the underlying principle of owning income-producing assets has remained resilient across very different political and economic eras. FIRE does not remove policy risk, but can reduce dependence on it.

5. Extreme frugality could reduce present-day quality of life

Some critics argue that FIRE encourages deprivation, by skipping life experiences, delaying joy, and optimizing life around numbers rather than meaning. If the journey feels miserable, surely the destination may not justify the sacrifice.

Counterargument:

There are many flavours of FIRE. While early practitioners like Vicky Robbin, Mr. Money Mustache or Jacob Fisker (from Early Retirement Extreme) did advocate for leading ascetic lifestyles, nowadays there are nearly as many FIRE philosophies as there are people implementing them.

Coast FIRE, Barista FIRE, Lean Fire, Fat FIRE, and many other alternatives have emerged as different paths towards Financial Independence. From these, only the Lean FIRE path encourages extreme frugality. But in many cases, people who choose this path genuinely prefer a more frugal, less materialistic lifestyle in the first place.

The hardest FIRE questions aren’t financial—they’re about purpose, identity, and what replaces work’s structure. Photo by TheStandingDesk on Unsplash.

If the structural criticisms are mostly about feasibility and uncertainty, the psychological critiques that follow are about something deeper: what happens when work stops being the default container for meaning and community.

B) Psychological Risks of FIRE and Early Retirement

6. Early retirement can create a loss of purpose

In my view, this is one of the strongest arguments. Work provides structure, identity, challenge, and contribution. Removing it abruptly at a young age can potentially lead to emptiness. Psychological research on traditional retirees shows that loss of meaning is one of the greatest risks, so it’s fair to assume that this could apply even more to early retirees.

Counterargument:

The deeper issue here is not retirement but lack of intentional purpose. If you’re looking to retire early in the first place, chances are you weren’t getting meaning or a sense of fulfillment from your career in the first place—nearly 80% of global workers report feeling disengaged in their job.

But many financially independent individuals continue with work that’s meaningful to them—writing, volunteering, mentoring, participating more actively in their local community, or engaging in creative pursuits. Many of these endeavours are simply not well paid, so it’s difficult to create a career around them. However, this fact does not make their pursuit any less valuable.

But it’s true that folks pursuing FI need to think long and hard about these questions, and make sure they’re retiring to something more meaningful, not just looking for a quick escape.

7. Happiness gains may fade through hedonic adaptation

Humans have a inbuilt tendency to quickly normalize changes in their circumstances—whether good or bad. Hedonic adaptation is often cited in the context of lifestyle inflation, where you get accustomed to material upgrades much faster than you expect and return to your previous baseline of contentment. This can apply also to FIRE: the excitement of reaching the Financial Independence finish line may wear off much more quickly than you expect.

Counterargument:

The excitement of reaching FI will almost certainly fade, because it fades after nearly every major life milestone. But FIRE is not about preserving that feeling, but about changing the structure of your day-to-day life. Even when the novelty disappears, the ability to choose how you spend your time remains.

While hedonic adaptation may erase any sense of permanent thrill, it does not erase the sense of freedom from your life. Control over your time and autonomy are factors associated with long-term well-being, and these will always remain high.

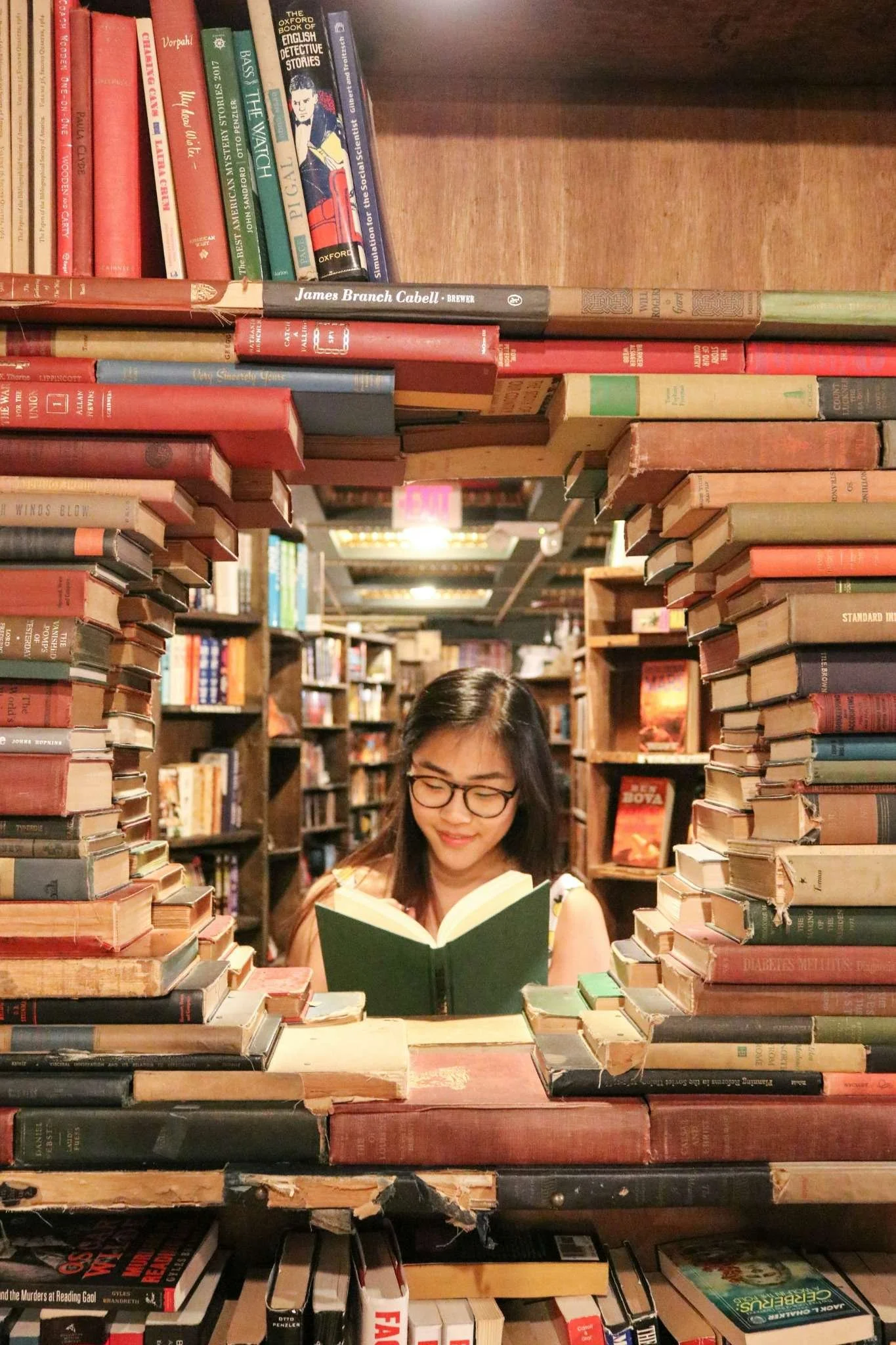

8. Leaving the workforce may reduce social connection

Daily interaction with colleagues provides structure and a sense of community or shared purpose. Without intentional replacement, early retirees—especially extroverts—may experience loneliness.

Counterargument:

Many workplace relationships fade naturally over time. If you look back on your career, chances are you no longer meet—or have lost touch with—colleagues from former jobs. At the time, you got along really well with many of them, but as time passes it becomes clear that the vast majority of career relationships don’t translate to outside the work environment.

In contrast, FI allows people to cultivate deeper, chosen communities through family involvement, local engagement, shared interests or hobbies, and friendships that are not tied to employment. Again, the key is retiring to something meaningful and being mindful of actively pursuing social connections.

9. A scarcity mindset may persist after reaching FI

For many, years of aggressive saving can make spending feel psychologically difficult. Some individuals reach Financial Independence, but because they pushed themselves too hard in their journey, now they actually struggle to enjoy some of its benefits.

Counterargument:

A persistent scarcity mindset is less a flaw of FIRE itself than a sign that inner work around money was never really addressed. As we’ve covered in previous posts, many of us unknowingly are carrying around “money scripts” we inherited from others, which we need to deal with—whether we’re pursuing FIRE or not. But it’s true that saving aggressively without examining fears or how your identity relates to money can simply carry some money anxieties into Financial Independence.

As mentioned earlier, there are many speeds and flavours of FIRE. Many of these alternatives allow people to pursue freedom without deprivation or developing some of these negative relationships with money. When the journey is paced with awareness rather than fear, reaching FI becomes less about hoarding resources and more about learning how to use money as a tool in service of designing a meaningful life.

10. Delayed gratification risks never being realized

Life is uncertain. Sacrificing too much today for a future that may never arrive feels risky.

Counterargument:

If you see Financial Independence as a binary proposition, then this argument has substantial merit. It’s true that you never know what’s around the corner; you may not even make it alive to your early retirement date. This is yet another reason for creating the conditions to design a more balanced path to FI, where you fully enjoy the journey. Don't cut back on things that truly bring you joy, but cut back mercilessly on all the fluff that doesn’t add any value to your life.

But also consider that the FI journey is not a binary proposition, but represents a gradual progression in freedom. Each stage of Financial Independence expands choices long before reaching retirement—whether it’s the ability and permission to change careers, work part-time, or implement recurrent mini-retirements.

If work provided built-in community, early retirement requires rebuilding social structure intentionally. Photo by David Xeli on Unsplash.

C) Social & Ethical Criticisms of FIRE

11. Retiring early may appear socially selfish

Some see FIRE as withdrawing productive labor from society or prioritizing personal comfort over contribution.

Counterargument:

This criticism assumes that contribution to society is measured primarily through paid employment, but human value is much broader than economic output. Many financially independent individuals redirect their time toward caregiving, volunteering, mentoring, creative work, or community involvement.

Many of these contributions are deeply valuable yet often unpaid. In addition to these endeavours, many become more present partners, parents, and friends, which strengthens the social fabric in ways traditional careers don’t. Depending on how it’s implemented, FIRE is not necessarily a withdrawal from society, but could enhance our place in it. Contribution to society extends well beyond paid employment and narrow career paths.

12. Wealth accumulation may reinforce inequality

Saving and investing grow capital, potentially widening wealth gaps and inequality.

Counterargument:

It’s true that capital tends to compound faster than wages, and this can widen the wealth gap at the societal level. But the existence of inequality is not created by individual households choosing to save instead of spend, but shaped far more by a combination of structural forces: access to education; labor markets that concentrate wage growth in specific sectors; housing policy that favors owners over renters; or taxation.

You could argue that, in this context, encouraging broader participation in saving and investing would serve more as a remedy to inequality. Expanding financial literacy and asset ownership gives more people a stake in economic growth instead of leaving wealth-building concentrated among a small minority. To illustrate this argument, think about the role Jack Bogle played in increasing market access to the general public through the creation of index funds.

In my view, FIRE is less about separating from society and more about democratizing tools that were historically limited to the already wealthy.

13. FIRE culture can feel moralizing or judgmental

FIRE messaging sometimes feels judgmental or moralizing, framing frugality as virtue and spending as a failure, or alienating people with different world views or values.

Counterargument:

As mentioned earlier, early voices in the movement sometimes did frame frugality in moral terms, but the modern FIRE landscape is far more plural with slow FI, Coast FI, Barista FIRE, family-centered approaches, Fat FIRE, and many hybrid paths shaped around personal meaning rather than ideology. Today, FIRE is more like a toolkit that individuals adapt to their own culture, income, and life priorities.

14. Passive investing may conflict with environmental values

Investing in index funds includes investing in fossil fuels and other controversial industries, raising concerns for environmentally-minded investors.

Counterargument:

This tension is real for environmentally-conscious investors, since broad index funds inevitably include industries with negative externalities. Yet the influence of any single passive investor on corporate behavior is extremely limited, while meaningful environmental change has historically emerged from regulation, technological innovation, and large-scale capital reallocation by governments and major institutions.

Although some investors pursue value-aligned strategies—through selective stock picking or ESG-tilted funds—these paths can be difficult in practice: stock picking has historically underperformed diversified passive investing, and many ESG products provide less real-world impact than their marketing suggests. In fact, in many common ESG frameworks, scores primarily reflect environmental, social, and governance risks to firms and investors, rather than the firm’s real-world impact on those dimensions.

At the market level, price discovery of individual companies is driven primarily by active trading, meaning the decisions of individual passive investors rarely translate into direct corporate pressure. For this reason, environmentally-minded FIRE practitioners may ultimately create greater real-world impact through how they consume, vote, advocate, and support systemic change than through small adjustments to a broadly diversified passive portfolio.

15. FIRE may shift too much responsibility onto individuals

Some critics argue that FIRE reflects a broader societal trend in which responsibility for retirement has moved away from institutions—pensions, unions, employers, and safety nets—to individuals. In this view, FIRE is less like a liberation and more like adaptation to an increasingly precarious economic system where each person needs to look out for themselves.

Counterargument:

This concern highlights a real structural shift in modern economies, but is not caused by FIRE itself. The movement can be understood instead as a response to that reality—an attempt to rebuild security where institutional guarantees are weakening and where job markets generally fail to provide a sense of fulfillment. While individual responsibility can feel burdensome, it can also create agency: the ability to shape one’s future rather than depend entirely on systems that are feeble or uncertain.

A central critique of FIRE is that responsibility for long-term security has shifted from employers and pensions to individuals. Photo by Lynn Van den Broeck on Unsplash.

D) Practical FIRE Risks (Planning, Burnout, and Re-entry)

16. Future expenses are easy to underestimate

Over long time horizons, the greatest uncertainty is often not inflation or markets, but ourselves. Families grow, interests evolve, health changes, and the life imagined at 35 very rarely matches the reality at 55. Financial plans build on today’s preferences can quickly become outdated, leading to spending needs that diverge from earlier projections.

Counterargument:

It’s true that no long-term plan can perfectly predict who we’ll become in the future. We covered this in detail in a dedicated post on “the end-of-history illusion”, a concept that reflects that we severely underestimate how much we’ll change in the future despite fully acknowledging how much we have changed in the past.

But the purpose of FIRE planning should not be total precision, but flexibility. Conservative assumptions, financial buffers, and adaptable spending in retirement can create room for lives that unfold differently than we thought they would. Any strategy should build enough margin to adapt to whatever future actually arrives.

17. Aggressive saving may cause burnout

Treating FIRE like a sprint can be both mentally and physically detrimental, undermining the freedom being pursued in the first place.

Counterargument:

When the FI journey is pursued as an urgent escape, the pressure to optimize every single expense and accelerate the early retirement timeline can indeed erode well-being. But this reflects a pacing problem, rather than a flaw in the destination itself.

Personally, I’ve done the trade of taking the foot off the gas, exchanging a lower savings rate and a slightly delayed FI timeline for enjoying a smoother journey. A sustainable FI journey should preserve health, relationships, and curiosity, ensuring the freedom reached at the end is actually usable.

18. Skills may atrophy after leaving traditional work

Reentering the workforce could become difficult after an extended absence.

Counterargument:

Stepping away from conventional employment reduces exposure to formal career structures, but does not necessarily stop personal growth and learning. Many FI individuals remain intellectually and professionally active through part-time work, creative projects, entrepreneurship, or continued study.

But more fundamentally, I think the very capabilities that were required to reach FI—discipline, adaptability, problem-solving, and long-term thinking—are enduring skills. Rather than disappearing once we reach FI, they can continue to be sharpened in the context of other forms of contribution.

19. Partners, family, or friends may not share FIRE goals

Pursuing FIRE doesn’t happen in isolation. Differences in attitudes towards spending, career ambition, or lifestyle priorities can create tension within couples, families, or close social circles. What feels like long-term security to one person may feel like unnecessary sacrifice or withdrawal to another, and these mismatches can quietly strain relationships over time.

Counterargument:

Differences in financial and life philosophy can create real tension, especially when one person’s pursuit of independence challenges shared norms around spending or career. Yet this challenge is not unique to FIRE, but arises in many major life choices involving risk, values, or long-term vision. For example, it can arise in something as simple as someone’s decision to rent instead of buying a house. If you rent, you can probably relate to how difficult it can be to talk to other buyers about this decision.

We covered recently in a post whether to communicate your FIRE plans to close friends and family. Open communication, gradual change, and leading by quiet example are often the best approaches. Even when full alignment never emerges, the opportunities lie in stressing the shared priorities—more security, time together, and freedom from stress. Most will be on-board with tackling those; and that is what FIRE is ultimately trying to support.

20. FIRE can become an identity rather than a tool

For some, the pursuit of FIRE can gradually shift from a means of gaining freedom to a central measure of identity and self-worth. Net worth milestones, savings rates, and retirement dates risk becoming proxies for progress in life itself, narrowing focus on optimization rather than meaning.

Counterargument:

Any meaningful pursuit, including career success, status, or productivity, can harden into identity if hold too rigidly. FIRE is no exception. When the number becomes the goal, the original intention of obtaining more freedom can narrow into another form of striving. But I think this risk points to a broader human pattern rather than a failure of FI itself.

Money cannot provide meaning, but it can create the conditions in which meaning is easier to explore. And used wisely, FIRE is not an identity to take on, but a space in which a more authentic life might gradually unfold.

FIRE is easier with aligned values—misalignment with partners or friends is a real (and solvable) friction point. Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash.

Which Criticisms Matter Most?

While I acknowledge some of the valid criticism directed at the FIRE concept and movement, I think most of the arguments are not too difficult to overcome. Being mindful of some of these issues early on can make your journey to FI much smoother.

Among all the concerns, personally two stand out as particularly important ones to be mindful of and address early on:

Loss of purpose—make sure you’re retiring to something, not just away from something

Loss of social connection—make sure you proactively build a social network that can replace, where needed, the role work currently plays in your life. After all, you spend around 40 hours each week there; even if most colleagues aren’t close friends, work still provides regular interaction and shared structure that must be recreated intentionally

These are not spreadsheet problems. They are human problems; the same questions faced in any type of retirement, career change, or major life transition.

FIRE does not create these challenges. It simply asks us to confront them earlier, and perhaps more consciously, than we otherwise would.

Who Should Probably Not Pursue FIRE?

FIRE may be a poor fit for people who:

derive most of their identity and meaning solely from career status

strongly prefer present material consumption over future time freedom

experience severe anxiety around money or scarcity

feel little interest in exploring or designing life beyond traditional work

This is not a moral judgment, just a recognition that different philosophies of life naturally lead to different choices.

Final Thoughts

After thinking through these arguments, I’ve come to feel some of the criticisms of the FIRE concept are both thoughtful and valid. They remind us that spreadsheets alone cannot answer the deeper questions about meaning, identity, or fulfillment. Critics are right to caution that money by itself cannot create meaning, that extreme frugality can become counterproductive, or that retirement (traditional or early) without a sense of purpose may feel empty rather than liberating.

At the same time, some concerns go too far. Financial Independence is not reserved only for the wealthy, nor is the simple act of saving and investing socially harmful. And while freedom from mandatory work can feel unfamiliar, it’s not inherently dangerous. It is possible to find and engage in a myriad of other activities outside of a corporate workspace environment and find meaning and fulfillment.

FIRE is neither a miracle solution to all your personal problems nor a misguided illusion. It’s simply a tool, one that can narrow life if used too rigidly, or expand it if used with reflection and intention. Like any tool, its value depends less on the concept itself and more on the wisdom with which it is applied.

If you enjoyed this article, here are some next steps:

👉 Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free, email unlock) to estimate your timeline to early retirement

👉 New to Financial Independence? Start with our Start Here guide for the full framework.

👉 Subscribe to The Good Life Journey (free tools & monthly newsletter, unsubscribe anytime)

💬 Do you think financial independence is mostly about escaping work—or about creating the freedom to choose more meaningful work? What would that look like for you? Let us know in the comments.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing—with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

Check out other recent articles

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The biggest criticisms fall into four buckets: structural (high savings rates can be unrealistic), financial (market/sequence risk), psychological (loss of purpose and social structure), and ethical (investing in controversial industries or inequality). Not all are equally strong, but the best critiques highlight real human risks—especially around meaning and identity after leaving a traditional career.

-

The most common drawbacks are burnout during the accumulation phase, underestimating future expenses, and the emotional trap of making FI a finish line rather than a tool. Some people also struggle with loneliness or loss of structure after exiting full-time work. The antidote is usually flexibility: slower FI, partial FI, and retiring to something meaningful.

-

Retiring early can reduce daily structure, purpose, and social connection—especially if work was a primary source of identity or community. It can also increase financial uncertainty because you’re funding a longer retirement. The solution isn’t necessarily “don’t retire early,” but to plan for purpose, community, and flexibility alongside the numbers.

-

Extreme early retirement is easier on a high income, but FI exists on a spectrum. Even moderate savings rates can meaningfully pull retirement forward and increase career freedom long before full FI.

-

It can be unrealistic if interpreted as a single rigid template: save 70%, retire at 35, never work again. But many people pursue FIRE as financial independence and optionality—working less, switching careers, or choosing lower-stress work. The realistic version adapts to income, geography, family, and values.

-

Many people don’t quit financial independence—they quit an extreme approach that made life feel narrow or joyless. Common reasons include burnout, guilt about spending, social isolation, or realizing early retirement didn’t solve deeper purpose questions. A healthier pivot is often “FI, but flexible”: slower timelines, meaningful work, and intentional spending.

-

Not necessarily. The excitement of reaching FI can fade, but FI changes the structure of daily life: autonomy, flexibility, and reduced stress. Even if the emotional “high” disappears, freedom remains—and living from a baseline with more control over time can still be a profound improvement.

-

At a societal level, compounding returns can widen wealth gaps. But inequality is shaped far more by education access, wage dynamics, housing policy, and taxation than by one household saving more. Broadening investment access and financial literacy can also be a partial remedy by helping more people build assets instead of only a small minority.

-

This is a real tension: broad index funds include industries with negative externalities. But individual passive investors have limited direct influence, and large-scale change often comes from regulation, technology, and institutional capital. Many environmentally minded FIRE followers focus on high-impact levers like consumption choices, political engagement, and supporting systemic reforms.

-

Purpose and people. Plan what you’re retiring to (projects, work, volunteering, learning), and actively replace the social structure work used to provide. The financial plan matters—but the psychological plan is usually what determines whether FIRE feels liberating or empty.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>