the End-of-History Illusion: Why You’ll Change More Than You Expect

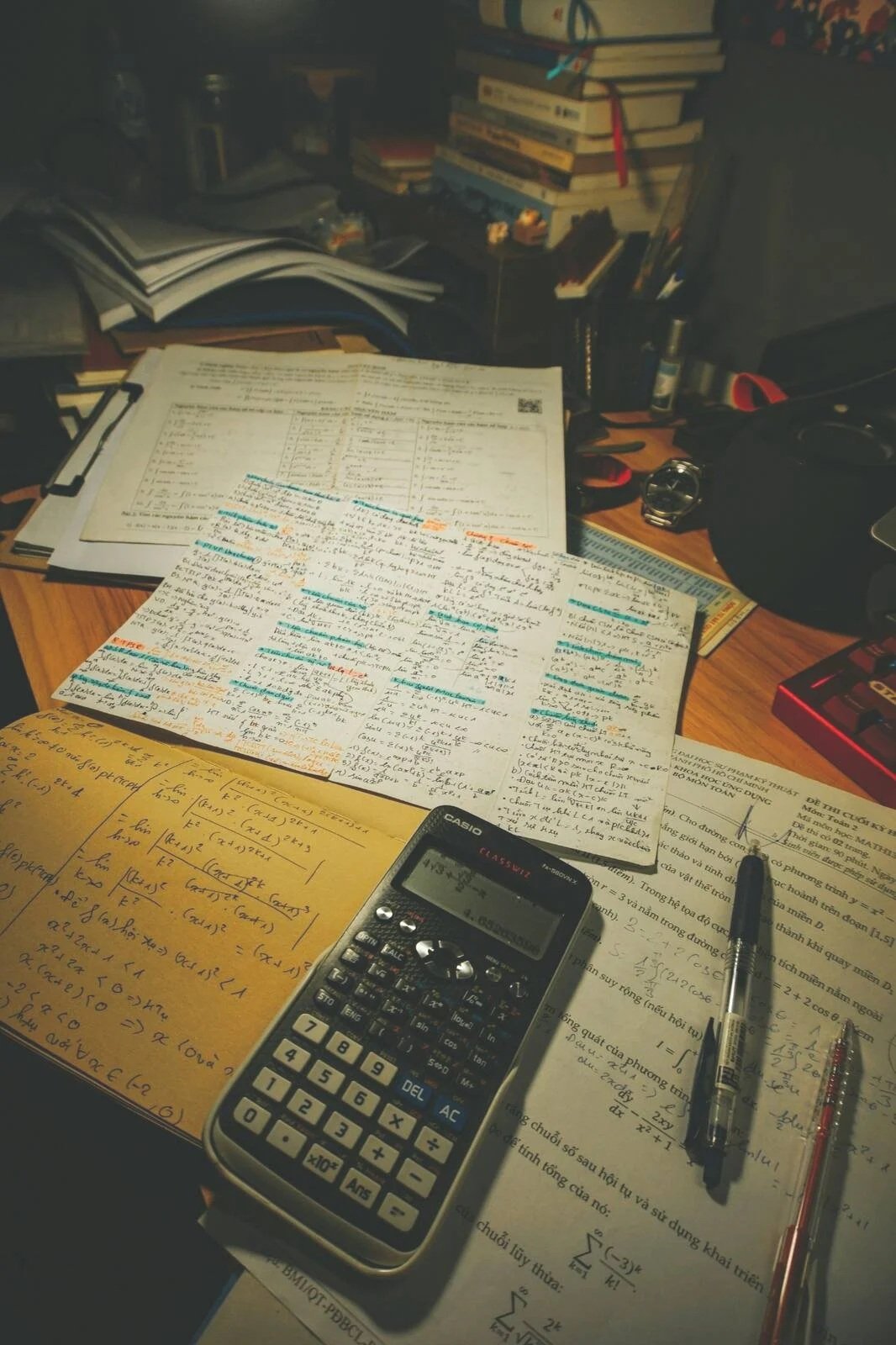

The End-of-History Illusion refers to how we underestimate how much we’ll change in the future, despite being aware of how much we’ve changed in the past. Photo by Raed Kasrwani on Unsplash.

I’ve spent the past 15 years watching my priorities change in ways my younger self couldn’t have predicted—from how I view money and careers to how I think about health, work, and what a good life actually means. This article draws on that lived experience, alongside research from psychology, to explore why long-term planning is harder than we think.

TL;DR — The End-of-History Illusion & Life Planning

🧠 We underestimate how much we’ll change, even though past change is obvious

📉 This bias leads to a rigid life and financial plans that age poorly

💰 Financial Independence works as insurance against unpredictable future selves

🏃 Health investments compound into freedom, just like money

🧭 The smarter goal isn’t optimization—but optionality

⚖️ Extremes feel right now; moderation tends to age better

The End-of-History Illusion: Why Planning for a Life You Can’t Predict Still Matters

We all know we’ve changed substantially over the past decade—yet we often assume that from now on, we’ll remain mostly the same. I don’t write this as a theoretical concern. Over the past 15 years, I’ve changed profoundly: how I think about money, careers, politics, health, work, and even what I consider a good life. Many of these shifts were not only unexpected—they would have sounded implausible to my younger self.

Why do we expect our future self to change less ten years from now than we did in the last decade? Psychologists call this bias the End-of-History Illusion—the tendency to believe that who we are today is close to a finished version of ourselves. In this article, I’ll briefly explain what the End-of-History Illusion is (with real examples), and then explore why it matters so much for long-term decisions around money, careers, health, and lifestyle design.

You’ll walk away with a clearer mental model for long-term planning under uncertainty, and with practical principles for building flexibility without becoming extreme or joyless along the way.

What Is the End-of-History Illusion—and Why It’s a Planning Error

Long-term planning is difficult because people change. It’s not just their circumstances, but their values, desires, and identity. Psychologists call this the End-of-History Illusion: the tendency for people to recognize how much they changed in the past, while underestimating how much they will continue to change in the future. In simple terms, the End-of-History Illusion is the belief that who we are today is close to a final version of ourselves.

We look back ten or fifteen years and see a different person—at least, I do—yet somehow we believe that who we are today is the finished product of ourselves. A common example of the End-of-History Illusion is assuming that your current career ambitions, lifestyle preferences, or tolerance for financial constraint will feel just as right twenty years from now—despite clear evidence that they didn’t feel the same twenty years ago.

This illusion can quietly sabotage our ability to plan well for the future. Part of the reason is psychological: our present self feels vivid and real, while our future self feels abstract—making change harder to imagine than it actually is.

I originally came across this concept in The Psychology of Money. Seen through a financial lens, this illusion can become a genuine planning error. Specifically, it can lead us to overcommit to plans that assume our preferences, energy levels, and constraints will remain stable—when history suggests the opposite. And so we tend to lock ourselves into lifestyles, spending levels, careers, or ideologies that assume a static self.

This is where overconfidence often creeps in, especially in our 20s and early 30s when life is simpler, health is abundant, and obligations tend to be more limited. For instance, choosing Lean FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early), pursuing hyper-optimization, or some rigid financial blueprint can feel perfectly rational at a certain moment of our lives, even though life often becomes more complex in ways that are difficult to predict. What felt sustainable when life was simple can feel constraining once responsibilities, health trade-offs, and priorities evolve.

Researcher Daniel Gilbert (and colleagues) showed in their work The End of History Illusion—published in Science— that people were willing to pay significantly more money to relive an experience from their past than to pre-experience something from their future—even though the future experience would be new. The implication is that we feel emotionally connected to who we were, but strangely disconnected from who we will become.

In reality, research suggests that people continue to change just as much in adulthood as they did earlier in life—we simply fail to anticipate what those changes will be.

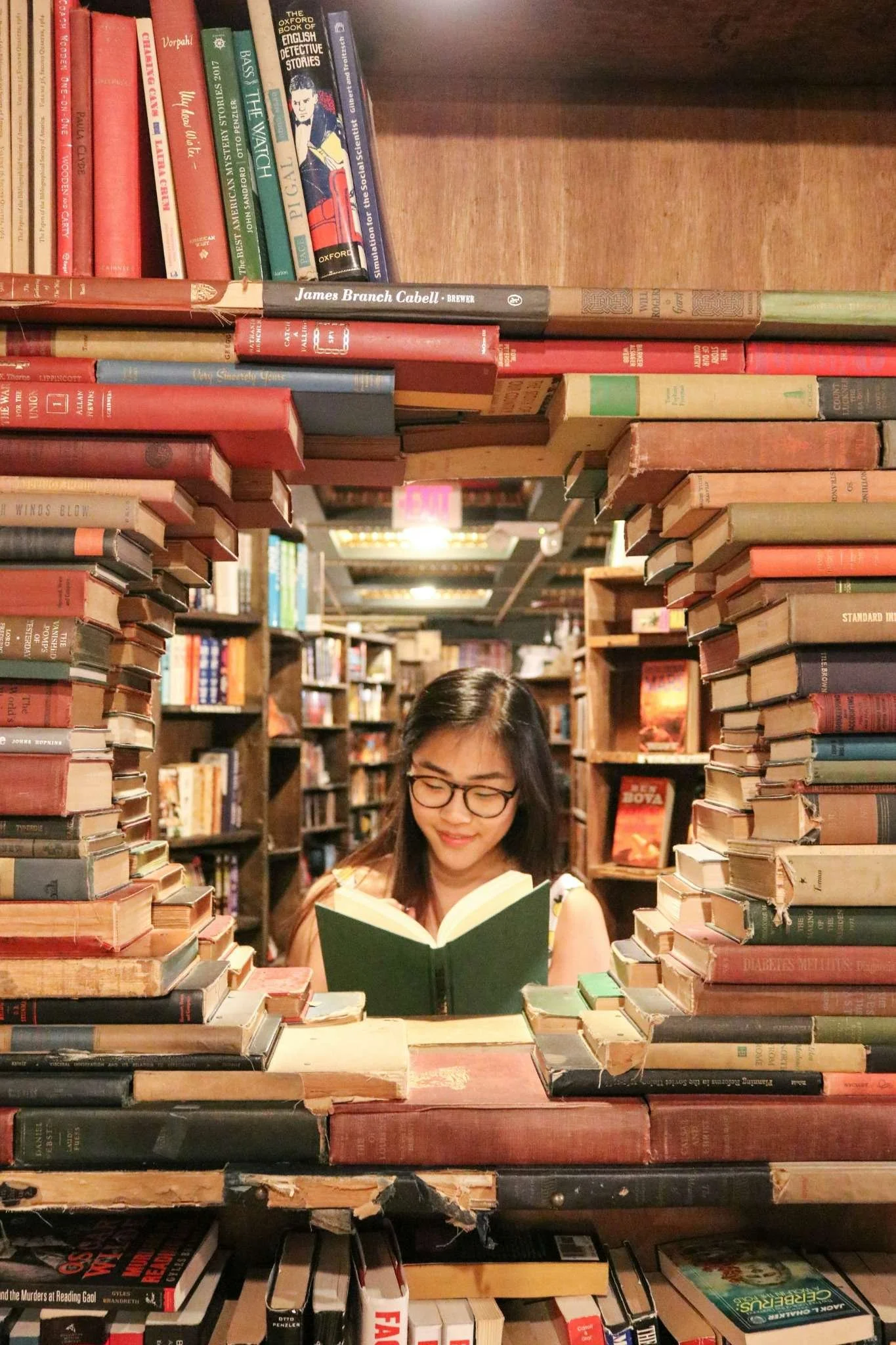

We should at least consider the possibility that the journeys our future self engages in are different than the ones we care about today. Photo by Tobias Rademacher on Unsplash.

How the End-of-History Illusion Shapes Money Decisions and Financial Independence

Convincing a 20-year-old to save and invest is notoriously difficult—for understandable reasons. At that age, life feels expansive, identity is still forming, and money often ranks low on the list of concerns. When I was in my early 20s, money was certainly a very secondary concern. Even when I worked hard, it was rarely about maximizing financial outcomes, but more about building an interesting career, following curiosity, or buying into the prevailing narrative that work itself would be the main source of meaning and happiness.

The problem isn’t that the mindset is entirely wrong—though I personally think it might be—but that it assumes continuity. The reality is that by 35 or 40, many people experience a sharp shift in their lives: mid-life crises, burnout, family responsibilities, health concerns, a desire to slow down, or the urge to change direction entirely.

At that point, flexibility suddenly becomes invaluable. And while it was hard to predict exactly who you’d become or what specific problems you’d have to face, it’s remarkably likely that your future self would appreciate having a strong financial buffer. Saving for Financial Independence doesn’t have to be about predicting the future; it’s about acknowledging that your future preferences will likely differ from today’s—financially, professionally, and even physically—and therefore preserving optionality is often the wiser bet.

This was certainly the case for me. After 7 years into the FI journey, I started experiencing a lot of the above-mentioned issues. Had I not been on this financial journey, I’m not sure I would have had the mental bandwidth or courage needed to step away from my job and career, ask some difficult questions, and try to realign my life with my values and lifestyle preferences. In this sense, saving diligently bought me an unexpected peace of mind and optionality.

This is also where moderation becomes important. Extremes often feel right in the present moment, but moderation tends to age better. Saving aggressively doesn’t necessarily require deprivation or some extreme form of asceticism. A simple principle works surprisingly well over time: pay yourself first—make saving the first “expense” of the month, and then spend intentionally on things that genuinely move the happiness needle for you with the remainder.

This approach leaves room for both present enjoyment and future adaptability to who you’ll become—a balance your future self is very likely to thank you for.

Financial Independence as Insurance Against Future-You Surprises

Financial Independence is often framed as a destination—a number, a date, or a finish line. But viewed through the lens of the End-of-History Illusion, FI looks less like a destination and more like insurance. Many people reach their late 30s or early 40s with a strong desire for freedom, flexibility, or change, only to realize they’ve locked themselves in with very little room to manoeuvre.

Careers feel rigid and difficult to change, expenses are usually high, and responsibilities only continue to increase. Now you’re not only responsible for a young family, but soon you will also be responsible for caring for your parents too. This is the “Sandwich Generation” and it’s no wonder this age group feels exhausted—they’re often also at the peak of their careers, working full time with a lot of responsibility.

The timing is rarely ideal—the desire for change often comes precisely when optionality is most constrained.

My own FI journey shows a different dynamic is possible. We started saving aggressively seven years ago or so, often with savings rates above 50%, yet without feeling materially deprived. We simply were very intentional about aligning our spending with what really brought us joy, and tried to cut out everything else.

At the time, I didn’t really know exactly what we were saving for—other than this cool-sounding Financial Independence milestone sometime in the distant future—the “Crossover Point”. Surprisingly, what discipline bought me instead—much sooner than at FI—was the ability to step away from a demanding career during burnout and pivot towards something more part-time, entrepreneurial, and aligned with how I had changed in the last years.

In hindsight, FI hasn’t only been about early retirement, but about being prepared for a version of myself—and a life after FI—that I couldn’t anticipate 10 years ago.This is one of the common misconceptions of the FI journey—you often start reaping the benefits of FI way before hitting your FI number.

Over time, this perspective has also softened my own views on FIRE (Financial Independence, Retire Early) itself. Early on, it’s easy to become overconfident—to believe that a tightly optimized plan, a lean lifestyle, or a rigid target will remain appealing indefinitely. It incorrectly assumes we don’t change.

But life often introduces new variables in the form of children, aging parents, health trade-offs, or simply evolving lifestyle preferences. Embracing the FI journey with a moderate mindset—not as some ideology, but as a tool—can reduce the risk of regret. It allows you to stay flexible without dropping the core principles that make FI powerful in the first place.

Importantly, this illusion doesn’t stop at money—it quietly shapes how we think about work, beliefs, and even our bodies.

Don’t automatically assume you’ll continue to be passionate about your career as you approach your 40s—entirely different interests may emerge or life could throw you several curveball of its own. Photo by Vitaly Gariev on Unsplash.

Careers, Beliefs, and Health: Why We Expect to Change Less Than We Do

The End-of-History Illusion doesn’t just apply to money—it shapes how confident we are that our careers, beliefs, and identities won’t change much either. Fifteen years ago, I had fully bought into the “specialist” career narrative—pick a path, go deep, and specialize relentlessly.

Today, I see my career very differently. I’m far more drawn to being a generalist instead, learning across domains, picking a variety of experiences, and even embracing the concept of sequential careers. This is a shift that would have been impossible to predict in my 20s.

The same pattern applies to how I see and engage with the world. Earlier in life, my views on politics (or on climate change) were far stronger—sometimes confrontational. Over time, though, I’ve developed a more nuanced understanding of complexity, trade-offs, and historical context. I’m much more willing to admit a lack of understanding than I used to be.

I still care deeply about human progress, but I’m less interested in purity tests or playing the blame game. This moderation isn’t apathy, but a recognition that staying engaged over multiple decades requires resilience, humility, and an awareness of how much our perspectives evolve.

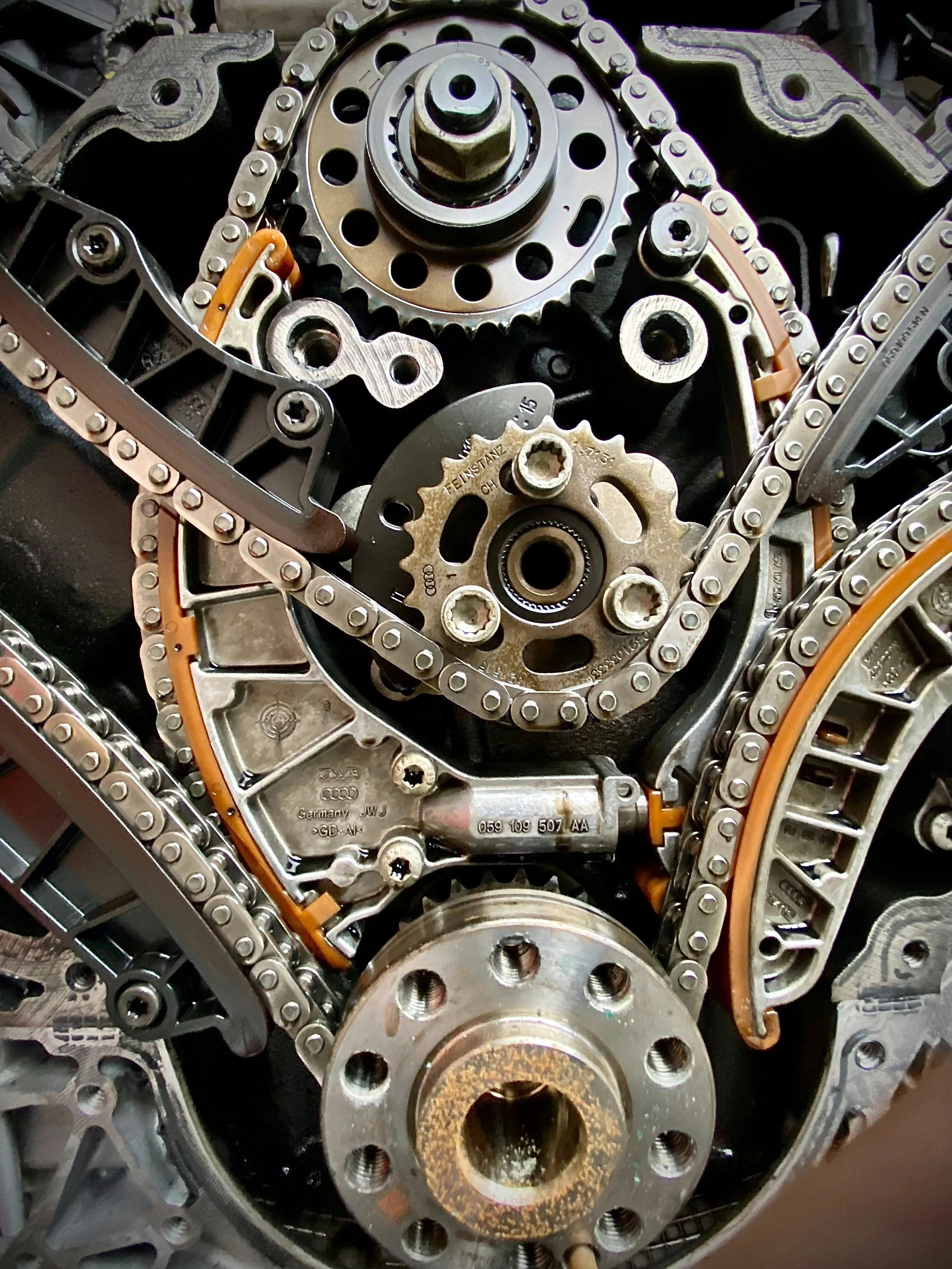

Health may be one of the most striking example of all. In my 20s, I exercised but paid little attention to long-term health metrics. Today, as a father, I think very differently about health. I now care about VO₂ max, resistance training, nutrition, and longevity—optimizing not just for lifespan, but healthspan too.

Like investments, health habits compound over decades, shaping not only how long we live but what the quality of those years will be. Of course, it also determines the quality of your present.

Health is often referred to as an asset, but I’d like to take this a step further. Much like with financial independence, good health quietly expands your future choices—what work you can do, how independently you can live, and how long you can stay engaged in the world. Analogous to pursuing FI, investing early on in health may provide a degree of optionality further down the road that we can’t fully comprehend today.

Just as FI gives the freedom to redesign life before retirement, health investments could also expand what’s possible later—what projects you engage in, how long you can stay active, and how independently you can live.

Pursuing FI was not about an end date after all, but about allowing me to redesign my life and switch careers. Similarly, investing in lifespan and healthspan will not just be about making it to a certain age in good health, but about all the things you will be able to do with it then.

An example of something I care about much more now—longevity and improving my VO₂ max, resistance training, or nutrition. Invest in your health like you invest in your index funds. Photo by Gold's Gym Nepal on Unsplash

Should We Optimize for Optionality, Not Optimization?

So, what does all this imply for the future? If the End-of-History Illusion is real—and the evidence and my own experience suggests it is—then perhaps the goal isn’t to design a perfectly optimized life, but a resilient one. Perhaps the better question isn’t how to optimize for a single future—but how to preserve optionality across many possible futures.

This doesn’t invalidate FIRE principles, but it does reframe them. Saving, investing, and building skills aren’t about locking in a specific vision of life at 50 (designed in your 20s or 30s), but about creating sufficient room for different versions of yourself you can’t yet imagine to flourish.

This mindset also helps resolve a common objection: doesn’t flexibility come at the cost of commitment? I think there is a distinction to be made here. Some commitments deserve to be hard and enduring—relationships, core values, building financial independence—while others may benefit from remaining soft and reversible—career paths, geographic choices, lifestyle inflation, or ideological rigidity. Distinguishing between reversible and irreversible decisions allows you to go “all in” where it matters most, without overcommitting in ways that constrain future growth.

Ultimately, respecting your future self requires a sense of humility. Most of the changes that shaped my life over the past 15 years were not the ones I had confidently predicted. This realization alone argues for moderation going forward. Again, extremes often feel right in the moment, but moderation tends to age better and be the wiser bet.

Build Financial Independence, invest in health, nurture relationships—and leave space for surprises. The goal isn’t to outsmart your future self, but to give it room to emerge.

💬 What’s one aspect of your life you’re most confident will stay the same over the next 15 years—and what evidence do you actually have for that belief?

👉 Want to understand how to reach Financial Independence in your mid-40s? Check out what savings rate will get you there depending on age and current portfolio size.

👉 Looking to retire a decade or more early? Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free for email subscribers) to plug in your numbers and see how soon you could go into retirement.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimers: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The End-of-History Illusion is a psychological bias where people recognize how much they’ve changed in the past but underestimate how much they will change in the future. It leads us to believe our current preferences and identity are relatively fixed.

-

A common example is assuming your current career, lifestyle, or spending preferences will still feel right in 20 years—despite having changed dramatically over the last 20. Many financial and life regrets stem from this assumption.

-

No. Research shows people continue to change at similar rates throughout adulthood. The illusion lies in our failure to anticipate future change, not in reduced personal growth.

-

Because we feel emotionally connected to our past self but disconnected from our future self. This makes current preferences feel permanent, even when history contradicts that belief.

-

It leads people to overcommit to rigid plans, underestimate future expenses, or assume lean lifestyles will always feel acceptable. This can reduce flexibility later in life.

-

Yes. FI can be seen as insurance against unpredictable future changes—career burnout, health issues, or evolving priorities—by preserving optionality.

-

Not necessarily. Lean FIRE can work well early on, but the illusion arises when people assume their tolerance for constraint won’t change as life becomes more complex. Some people will be just fine with Lean FIRE.

-

Many people underestimate how much they’ll care about health later in life. Early health investments compound into greater physical and lifestyle flexibility in older age.

-

It means designing finances, careers, and habits to keep choices open—rather than optimizing narrowly for a single future vision that may no longer fit.

-

Focus on moderation, reversible decisions, financial buffers, and long-term health. These strategies age well across many possible future versions of yourself.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,103);

});

</script>