The Inflation of Expectations: Why Life Feels Harder (Even When We’re Richer)

Social media often exposes us to curated lifestyles that quietly raise expectations about what a “normal” life should look like. Photo by Jake Nackos on Unsplash.

Reading time: 6 minutes

Quick answer:

The cost-of-living crisis is real, especially since 2020. Housing, energy, and food became much more expensive in many countries.

At the same time, over the longer arc of several decades, living standards have still improved in important ways.

So both things can be true: life got costlier in the short term, but richer over generations. What makes it feel especially hard today is not only prices—it’s rising expectations and constant social comparison that reset what feels “enough” to us.

What you’ll get in this article

✔ Why life can feel financially harder even despite long-term progress

✔ Why we’re materially better off than past generations in many ways

✔ What “expectations inflation” means—and why it determines life satisfaction

✔ How social media amplifies dissatisfaction through comparison and visibility

✔ Practical ways to redefine “enough” without denying real challenges

TL;DR — inflation is also about our expectations.

💥 Cost-of-living pressures since 2020 were real—especially housing, food, and energy

🏠 Housing hits hardest because it’s both a cost and a status marker

📈 Long-run progress is still extraordinary across health, tech, comfort, safety

🧠 Hedonic adaptation resets the baseline after improvements

📱 Social media intensifies comparison; extremes start to feel “normal”

🎯 Expectations inflation raises the cost of feeling satisfied

🧭 Don’t ignore real costs—but don’t ignore the psychology at play either

🔑 Define “enough” intentionally—so time, not status, becomes the real measure of wealth

The Hidden Inflation: Why Modern Life Feels Harder—Even When We’re Richer

Across the developed world, many people feel life has become financially harder, especially since 2020. Housing dominates the conversation, with food and energy close behind. It’s no surprise that many younger adults worry they won’t reach the stability their parents had. And yet zooming out over recent history, material standards, health, safety, and access to opportunity have improved dramatically.

This article explores that tension between genuinely-felt short-term pressures and long-term progress, and introduces a quieter force shaping some of our modern dissatisfaction: the steady inflation of our expectations.

Understanding this gap won’t fix real challenges, but it may offer clarity, reduce unnecessary anxiety, and help redefine what “enough” could mean in an age of constant comparison—where our sense of prosperity is shaped as much by the lives we see around us as by our own material consumption.

Sharp increases in everyday essentials like food helped drive the post-2020 sense that basic life was becoming more expensive. Photo by Nahrizul Kadri on Unsplash.

Is the Cost-of-Living Crisis Real? The Short-Term Squeeze

Since around 2020, many households in countries like the US, UK, or Germany have felt cost pressures more strongly than they did during the decade before. Everyday essentials like food, housing, and energy were simply rising much faster than most wages, creating the widely discussed “cost-of-living crisis.” In the US and UK especially, this has fed a broader feeling that basic middle-class life is becoming “unaffordable”. Although current inflation has eased noticeably across OECD countries, wages have generally not caught up with the increases we saw in costs.

Although I was not personally experiencing a financial crisis, I still remember feeling frustrated at work during that period. Between 2021 and 2024, inflation in Germany seemed to surge, yet annual salary increases for many colleagues remained modest. It created a strange tension: our own compensation felt largely stagnant, while at the same time we were routinely passing inflation-adjusted price increases on to clients for our consultancy services.

For many families, budgets have become tighter, savings feel slower, and long-term planning feels more uncertain than it did before. Acknowledging this reality is important, because any reflection on modern prosperity should begin with the pressures people are feeling today.

Housing stands apart from other expenses because of its emotional and cultural weight. In many societies—especially in the US, but also across many developed countries—homeownership is intertwined with identity, stability, and the sense of “making it.” And yet many structural factors such as limited housing supply, restrictive zoning, urban concentration of jobs, and other factors have pushed ownership further out of reach for younger generations compared with their parents at the same age.

This helps explain, on top of the general price increases, why economic anxiety feels so acute even when other prosperity indicators have improved over time. Housing is not just another item on the list; in many cultures, it’s a symbol of security and adulthood. Because of this symbolic weight, housing also becomes a powerful site of social comparison—a visible marker of whether we feel ahead, behind, or merely keeping up with those around us.

The nature of work has also shifted. Stable, decades-long careers with a single employer are obviously less common nowadays, replaced by more fluid job markets and more dynamic industries. Even when incomes are historically solid, this sense of volatility can further add to the persistent feeling of financial unease. In other words, I want to make the point that modern stress is often driven less by absolute poverty than by rising uncertainty across important parts of life.

There’s another, less visible change behind the income numbers—one I’ve felt intuitively when thinking about my own childhood. In many developed countries, rising household incomes over recent decades partly reflect the transition from single-earner (which was very common when I was growing up in Southern Europe) to dual-earner families rather than dramatically higher pay per worker. This shift reflects important social progress and expanded opportunities, but it also changes how economic security is experienced day to day.

Data broadly supports this pattern. For households remembering a time when one income could sustain a middle-class life, modern security can therefore feel more fragile—even amid genuine long-term material progress. But this tension coexists with undeniable long-term gains in material comfort, health, and opportunity—reminding us that perceived insecurity and real progress can rise at the same time.

Housing carries both financial and social meaning, making affordability pressures feel especially personal and visible. Photo by Andreas Strandman on Unsplash.

Do We Live Better Than Our Parents? The Long Arc of Progress

Stepping back from the last decade to view multiple generations reveals a different picture. Across advanced economies, and even more dramatically across much of the developing world, real incomes, life expectancy, childhood survival, education access, and physical safety have improved in ways that would have seemed remarkable to our grandparents.

Many hardships once considered normal, from untreated illness to dangerous workplaces to limited educational opportunities, have reduced substantially. Progress has not been linear or equal everywhere, but the broader trajectory has been unmistakably upward.

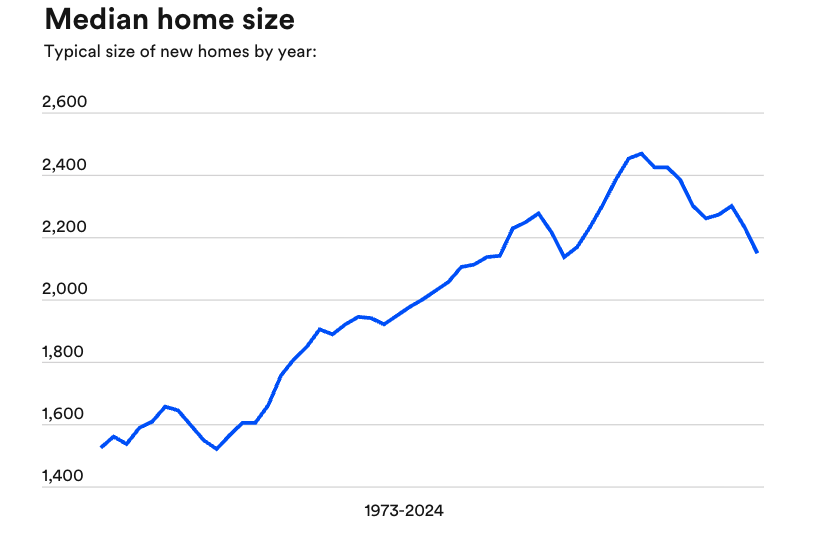

When we look at material living conditions we observe a similar story. Despite seeing a modest modest stabilization in recent years, home sizes in countries like the US today are about 50% higher than they were in the 1970s (see Figure 1). Household appliances, climate control, and conveniences that once require substantial wealth feel extraordinarily normal to us now.

Digital technology has amplified this shift: instant global communication, vast libraries of information, entertainment, or remote work capabilities—all at minimal cost. By historical standards, everyday life contains levels of comfort that were until very recently unimaginable. The issue is that comfort alone does not determine satisfaction. What matters just as much is how our lives appear relative to others, a comparison that has become far more intense in a digitally connected world.

Perhaps most striking is how many goods have become dramatically cheaper in real terms. Computing power, communication, media, and access to knowledge have fallen so steeply that traditional income statistics understate improvements in living standards. Even where headline costs rise, the overall bundle of what people can do, learn, travel, and experience with a median amount of resources has expanded enormously.

A lot of this we simply take for granted. Comforts that would have astonished our grandparents feel ordinary to us, not because they are insignificant, but because humans adapt very quickly to improvement. Psychologists refer to this as “hedonic adaptation”—our tendency to return to a relatively stable baseline of satisfaction even after positive changes in income, comfort, or convenience.

As material conditions rise, so do our own expectations, resetting what feels normal. The result is a modern paradox: extraordinary gains in living standards over one or two generations can coexist with a persistent feeling that little has improved or that things are getting worse—especially when rising expectations and constant social comparison continually reset what feels sufficient.

Figure 1: After a small dip in recent years, median home size in the US are still almost 50% larger than they were in the 1970s. Source. Bankrate.com based on 2024 US Census Bureau data.

Expectations Rose Just as Fast as Living Standards

Alongside material progress, another phenomenon has also been rising: the definition of what counts as a normal life. Features that were luxuries a generation ago—larger homes, private bedrooms for each child, frequent travel, constant connectivity, rapid product upgrades—have gradually become part of our baseline expectations.

Even as living standards improve, our threshold for feeling comfortable moves upward at the same time. This upward shift is reinforced by the simple fact that we rarely evaluate our lives in isolation—we measure them against the visible standards of our peers, our friends, and increasingly, the curated lives of strangers that we see displayed online.

This is what might be labelled as “expectations inflation.” Unlike price inflation, which raises the costs of goods, expectations inflation raises the cost of feeling satisfied. When yesterday’s progress becomes today’s minimum standard, people can become objectively richer while feeling no closer to security and success. The emotional experience of feeling behind persists, not because things haven’t improved, but because we keep moving the goal posts.

This distinction helps partially explain the modern paradox: rising prosperity without rising contentment. It also reframes frustration in a more compassionate way. This issue is not about entitlement or ingratitude, it’s a powerful psychological and cultural process that is inbuilt in humans which continuously resets what feels enough. It is a trait that has enabled incredible human progress over millennia. Recognizing this process is an important first step to regaining perspective.

Expectations don’t rise in a vacuum—they rise through what we see and who we compare ourselves to.

Features once considered luxury—spacious kitchens, design finishes, and appliances—have gradually become perceived necessities. Photo by roam in color on Unsplash.

Social Comparison Turned Local Feelings into Global Pressure

We are arriving at one of the most important points of this article. For most of human history, social comparison took place at a local level. People measured their progress against neighbors, coworkers, friends, and relatives whose lives were broadly similar to their own.

But today, social media and global connectivity expose us to a constant stream of carefully curated highlights from millions of people across the world. Extraordinary lifestyles that were once invisible to us now appear ordinary simply because they are repeatedly seen.

This amplifies a well-known cognitive effect called the availability bias. It emerges when we judge how common or important something is based on how readily examples come to mind, not on actual probability or reality. Because social platforms present exciting, polished versions of others’ lives, our minds start to treat those selective highlights as the norm.

This shift dramatically changes our emotional baseline. Comfortable homes, stable incomes, and meaningful relationships can begin to feel inadequate when contrasted against an endless projection of luxury travel, rapid success, or lives that appear easier or more fulfilled than our own. Even if the comparison is not “statistically fair,” this distorted visibility reshapes our expectations, and expectations reshape our sense of satisfaction.

Without conscious awareness, prosperity can feel strangely flat. The combination of our inbuilt hedonic adaptation with enhanced social comparisons in the digital space means dissatisfaction can grow even in the backdrop of real progress.

Stepping outside constant comparison can shift focus from status and consumption toward time, autonomy, and meaning. Photo by Michele De Pascalis on Unsplash.

The Real Crisis May Be Defining “Enough”

Research on wellbeing suggests that while rising income strongly improves life at lower levels of security, the relationship weakens once a certain level of comfort and stability are reached. Beyond that point, factors such as autonomy, relationships, health, purpose, and time freedom play a larger role in life satisfaction.

In other words, once basic security is met, having control over your time often matters more than accumulating additional material comforts. This is one reason why the idea of Financial Independence resonates so strongly with many people—it shifts the focus from comparison and consumption toward autonomy and choice.

This does not mean costs are irrelevant or that younger generations should simply change their attitudes. This article argues that both realities can coexist. Challenges like housing affordability are real and deserve structural solutions.

But alongside policy and economic change, there is also room for personal reflection. Some individuals pursue alternative paths that turn their back on metrics of status and social comparison or that intentionally implement lower levels of consumption to rebuild a sense of balance in an age of rising expectations.

In the context of Financial Independence, this can also mean reconsidering traditional milestones. When homeownership becomes financially stretched, some households may choose to rent while systematically investing the difference into diversified assets—pursuing long-term security through Financial Independence rather than property ownership alone.

Seeing expectations inflation clearly does not diminish real hardship. Instead it can help restore some sense of agency. It allows progress to be recognized where it exists (and to be grateful for it) and for comparison anxiety to soften. Ultimately, it is up to us to define what a good life means and to shift from endless comparison towards a place of deliberate sufficiency.

In a world that constantly raises the bar, learning to define “enough” may be one of the most important forms of freedom available to us. For some, that freedom becomes tangible through Financial Independence—not as an escape from work, but as the ability to choose how to spend one’s limited time. When expectations stop dictating lifestyle, time freedom can become a more meaningful measure of progress.

If this article resonated, here are a few next steps to explore the idea of “enough” in practice:

👉 New to Financial Independence (FI)? Start with the Start Here guide to the basics of FI

👉 Try our Financial Independence Timeline Calculator to see how close you may already be to greater time freedom

👉 Subscribe to The Good Life Journey for weekly insights on personal finance and early retirement

💬 Do you think life feels harder today mainly because of real costs—or because expectations and comparison keep rising? Please share your perspective in the comments below.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing—with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

Check out other recent articles

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Yes—especially since 2020, essentials like energy, food, and housing rose quickly in many countries. Even when inflation falls back, price levels stay higher, so households still feel the squeeze. That lived experience is real, even if the inflation rate has eased.

-

A mix of post-pandemic supply shocks, energy disruptions, higher interest rates, and housing constraints pushed prices up across many economies. The exact drivers vary by country, but the pattern—higher essentials—has been widespread.

-

In the UK, the term reflects a sharp rise in household bills—especially energy—alongside housing pressure and weak real-wage growth. Even when headline inflation comes down, many families still feel worse off because prices remain elevated.

-

For many people, it can feel that way—largely because housing, healthcare, childcare, and education have outpaced wage growth in many regions. At the same time, other goods (especially tech) got cheaper and living standards improved in many ways. Both can be true.

-

On many long-run metrics—health, safety, technology access, and material comfort—yes. But “better” is not only about consumption; it’s also about affordability, security, and time stress. The gap between objective progress and subjective experience is a central theme of this article.

-

Because satisfaction depends on more than absolute prosperity. Housing and insecurity matter a lot, and humans also adapt quickly to improvement (hedonic adaptation). Add constant social comparison, and “enough” keeps moving upward.

-

It’s when the definition of a “normal” life keeps rising—bigger homes, more travel, constant upgrades—so that yesterday’s luxury becomes today’s baseline. Unlike price inflation, it inflates the cost of feeling satisfied, not the cost of goods.

-

Social media increases exposure to curated, upward comparisons. That makes extreme lifestyles feel common and reshapes what we consider normal. Even when our own lives are stable, constant comparison can create a persistent sense of being behind.

-

Yes—some household-income growth reflects the shift from single-earner to dual-earner families, not just higher pay per worker. That can make “one income middle class” feel harder today. Yet long-run gains in health, tech, and material comfort still represent real progress.

-

Start with the basics: stabilize housing costs where possible, build a buffer, and focus on the biggest controllables (spending, skills, income). Then address the psychological layer: reduce comparison triggers, define “enough,” and align spending with values. The goal is both resilience and peace of mind.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>