friedrich Merz Wants Germans to Work harder

Political rhetoric about longer working hours sits at the center of Germany’s current economic debate. Photo: Tagesschau

Reading time: 7 minutes

Quick summary:

Germany’s Chancellor Friedrich Merz and his party Christian Democratic Union’s (CDU) business wing are arguing that Germans should work more—and that employees should no longer have the broad legal entitlement they currently do to reduce hours for “lifestyle” reasons. The proposal would keep some exemptions for parents, caregivers, and training, but shift everyone else toward needing justification or “permission” to go part-time.

In this post, I summarize what’s on the table, why supporters think it helps growth and pensions, and why I think the better route is incentives—tax reform, job mobility, and investment culture—rather than moralizing or restricting flexibility.

What you’ll get from this article

✔ What Merz/CDU propose and who would be exempt

✔ Why supporters think it helps growth, labor shortages, and pensions

✔ Why “work more” is about output—not necessarily productivity

✔ How taxes and incentives currently make full-time unattractive

✔ Why restricting part-time risks bureaucracy and stigma

✔ Smarter alternatives: incentives, mobility, investment culture, skilled immigration

TL;DR — Do Germans really need to work longer?

🧭 An economy may need more workers—but individuals still make rational choices to protect their health, time, and freedom.

🥕 If Germany needs more hours, it should reward them—not shame people into them.

🧾 High taxes and social contributions mean working full-time often brings only a small increase in take-home pay.

🤖 In an AI future, flexibility may be an adaptation, not a vice.

🏛️ Turning a right into “permission” creates bureaucracy and stigma.

Merz, “Lifestyle Part-Time”, and the Right to Work Less

Across Europe, and especially in Germany, a familiar argument is returning to the political stage: people must work more. The idea has been voiced most prominently by Friedrich Merz, Germany’s Chancellor and one of Europe’s most influential conservative leaders, who has criticized what he calls “lifestyle part-time work” and warned that Germany cannot maintain its standard of living “with a four-day week and work-life balance.”

Yet this push arrives at a surprising moment. Artificial intelligence promises to make economies potentially far more productive—reducing the total need for human labor even in the near future. Politics, meanwhile, is moving in the opposite direction, asking citizens to work longer hours rather than prepare for a world of less work.

The economic pressures behind this debate are real in many Western democracies: slow growth, aging populations, and growing financial pressure on pension and healthcare systems. In that context, longer working hours are increasingly framed as a civic duty rather than a personal choice.

This article doesn’t dismiss those macro concerns. Instead, it explores the deeper tension where economic necessity meets individual freedom. Two truths can exist at once: societies may need more labor participation, while individuals still rationally seek to protect their health, time, and autonomy. The real question, perhaps, is not simply how many hours we work—but what kind of life the economy is meant to serve.

Everyday workplace reality shapes how policies on hours and productivity are actually felt. Photo by Arlington Research on Unsplash.

What Merz and the CDU Actually Propose (and Who’s Exempt)

Germany’s economic worries are real. Growth has slowed, its population is aging, and many industries report shortages of skilled labor (e.g., across healthcare, IT, engineering, construction & skilled trades, education & teaching, or transport & logistics).

The logic assumes that more hours worked automatically means more prosperity. In reality, additional hours increase total output—but not necessarily productivity. Advanced economies grow primarily through innovation, technology, and capital efficiency rather than raw increases in labor time. When the debate focuses only on hours worked, it risks confusing motion with progress. A society can certainly be busier without becoming better off.

Still, the political appeal of the argument is easy to grasp. During uncertainty, narratives of discipline and effort feel somehow reassuring. Calling for harder work signals from leaders seriousness and responsibility. There is the temptation that as economies begin to struggle, we try asking more from individuals before trying to reform the system around them.

Within Merz’s political camp, proposals have included limiting the legal right to part-time work primarily to caregivers, parents, or those in formal training—effectively requiring others to justify working fewer hours. Beyond the practical difficulty that would arise from defining such categories or thresholds, this effectively would mean making part-time a matter of permission rather than entitlement.

Paradoxically, this push comes from a political tradition that normally champions market incentives and individual choice. Asking the state to restrict flexibility rather than improve incentives marks a notable shift—from trusting markets to disciplining workers. It’s no wonder that not everyone in his party agrees with Merz’s statements.

Labor shortages in skilled trades highlight where incentives—not mandates—matter most. Jeriden Villegas on Unsplash.

Incentives, Not Obligations, Drive Real Economic Behavior

When a society needs something, it can either reward it or mandate it—and those choices often reveal its values.

If a country really lacks labor, market economies should respond through higher wages or better conditions. This is exactly what has happened in the health sector. Over the last years, following a severe shortage in nurses, nursing salaries have strongly increased and outpaced wage growth of other sectors. We did not ask nurses to work more (despite being a sector with a high-share of part-time work); more nurses entered the field once incentives aligned.

When that pattern fails to appear, it often points to distortions elsewhere—most notably in the tax and contribution structure. For many middle-income workers in Germany, moving from part-time back to full-time produces only a modest increase in take-home pay once taxes and social contributions are applied. In that context, choosing fewer hours is not some cultural or moral failure, but a rational response to the incentives the system itself creates.

Imagine working 80% across four days—and gaining an extra day that is entirely your own. I lived that reality for years, and it completely changed my relationship with time more than any raise ever did.

The extra day isn’t just “leisure.” It becomes physical and mental health, learning, time with your family, and the mental space that makes you more focused and effective when you do work. Even without children or caregiving responsibilities, I would still resist any politics that labels people lazy simply for building meaningful lives outside the office.

Once you experience that change in quality of life, going back to full time work becomes extraordinarily difficult—especially when the financial reward is surprisingly small after taxes and social contributions. Would you really trade a three-day weekend for a marginal increase in take-home pay out of some abstract sense of macroeconomic duty?

Other structural levers exist as well—from faster skilled-immigration pathways to better recognition of foreign qualifications—none of which require restricting the freedom of those already working. At the same time, workplace surveys consistently show that many employees report excessive workload, stress, or unpaid overtime, complicating any simple narrative that the core problem is widespread idleness. According to the German Government’s own sources, there are about 4.5 million employees working extra hours.

Part-time work is protected in Germany as a right. Removing those rights risks treating the symptom rather than the cause. A system that would make full-time work more rewarding—through tax reform, easier job mobility, or wage growth—would likely increase labor participation without needing this type of top-down coercion.

To be fair, defenders of the proposal might respond that we simply don’t have time—that implementing the right incentives take years. While that concern may be valid, restricting part-time cuts both ways: removing flexibility can easily backfire by pushing people toward burnout, early exits, or disengagement—shrinking the long-run labor supply the policy is trying to expand in the first place.

There is also a broader fiscal reality. Tax revenues have generally risen over time in nominal terms. Today’s debate is really more about what future financial sustainability looks like under increasing demographic pressure. But that challenge cannot be solved permanently by adding hours alone.

The pension system needs to be reformed to encourage saving and investing by citizens early on; in the same way that Germany’s recent Early-Start Pension for kids goes in the right direction, more incentives are needed to encourage saving and investing by adults.

In the labor market, we need to make it easier for people to change jobs without staying out of the market for a full year or more. Gallup’s survey data shows that workers are generally unhappy in their jobs; allowing for a more fluid job market would certainly increase engagement and productivity in the workplace.

And this is where the macro story meets real life: people respond to incentives, but they also seek to protect their mental and physical wellbeing.

Modern offices promise balance—yet the deeper question remains how much of life should revolve around work. Photo by 2H Media on Unsplash.

The Individual Perspective: Rational Lives, Not Lazy Workers

At the individual level, the decision to work fewer hours often reflects careful optimization, not avoidance. People weigh different factors, including health, family, meaning, and long-term goals alongside income. But when work surveys show low engagement and dissatisfaction in modern workplaces, it becomes unsurprising that those who can afford more flexibility will choose it.

Expecting individuals to sacrifice well-being for marginal economic gain simply misunderstands how rational humans make decisions.

Labeling this behavior as lazy is more than inaccurate. It shifts attention away from stagnant job quality, limited job market mobility, and workplace stress, and places moral blame on workers instead of scrutinizing the systems that produce these outcomes in the first place. Over time, such narratives risk weakening trust between citizens and the systems that are means to support them.

Restricting part-time work to officially approved reasons would deepen that tension. Any rule defining what is an “acceptable” level of caregiving or personal development would require intrusive bureaucracy and subjective judgement over people’s private lives. Beyond being wildly unpractical, it signals something potentially more troubling: that economic pressure justifies shirking personal freedoms and gained workers’ rights.

Now let’s zoom out again—because the future of work makes this debate even stranger.

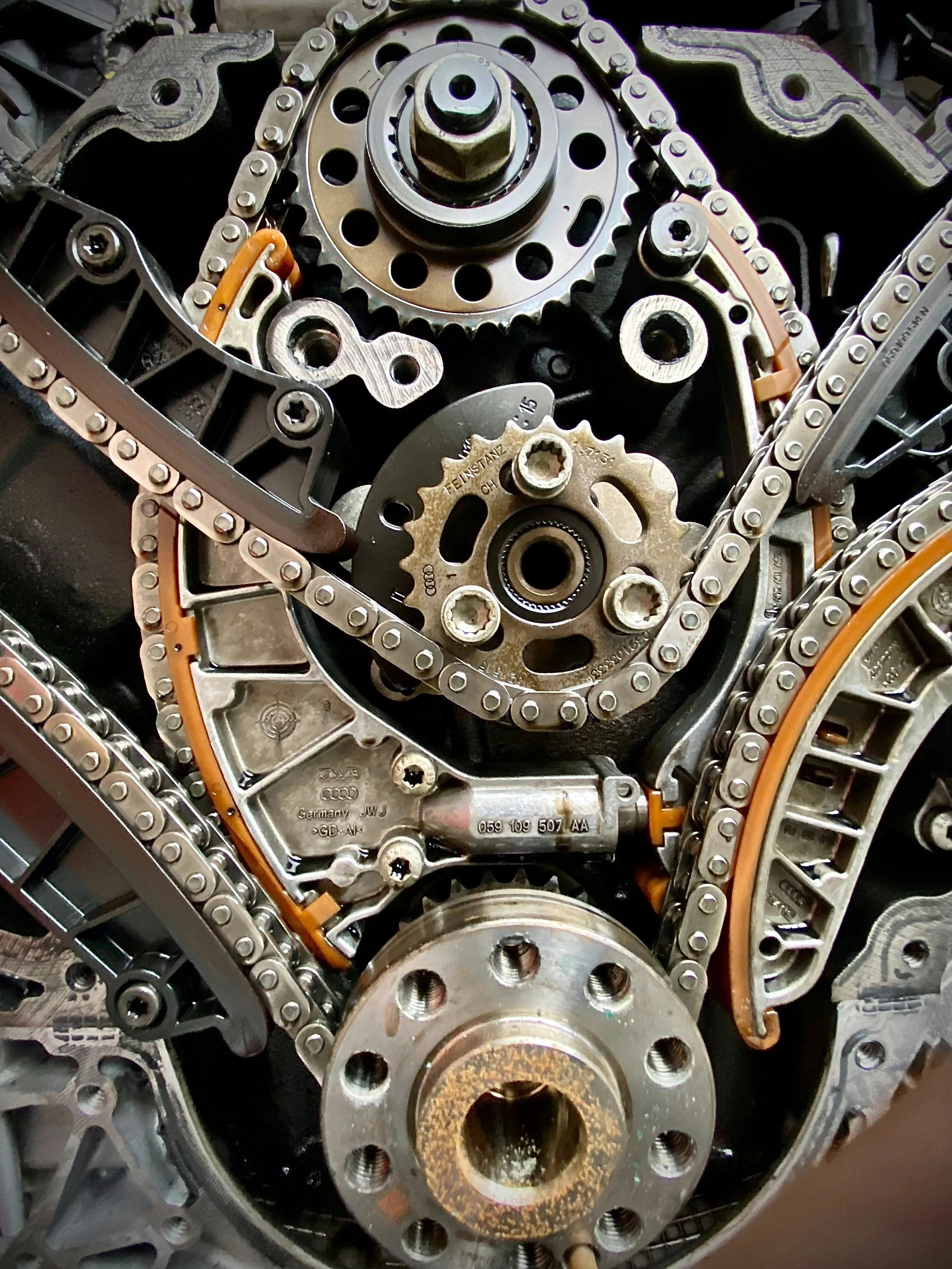

Automation and AI may soon reshape how much human labor economies truly need. Photo by ThisisEngineering on Unsplash.

Productivity in the Age of AI: A Growing Paradox

A deeper contradiction sits at the center of this debate. Just as AI and automation promise unprecedented productivity—potentially reducing the total amount of human labor required—political rhetoric is shifting toward demanding more hours from workers, not fewer.

Indeed, demands by politicians like Merz for longer working hours feel not only a bit dystopian but also not very forward-looking. Are they trying to apply some recipe from the past, whilst completely ignoring how to adapt our societies for a world with far less work? Will we look back in ten years in complete disbelief that our Chancellor was asking us publicly to work more hours?

It’s a bit like standing in the middle of the Industrial Revolution and announcing that what the economy really needs is more farmers—or watching the rise of personal computers in the late 90s and urgently calling for more typewriter production. Technological change rarely rewards doubling down on yesterday’s constraints.

It reminds me of an article I read recently, where a journalist argued for 60 year olds to “leave the golf course” and come back to work. What world are they talking about? Which companies are going to want to hire these 63-year-olds? If we face job shortages for graduates as AI starts rolling out, do we really want grandparents to return to the workforce?

Assuming productivity rises with AI while working hours remain rigid, societies may face the opposite challenge: how to distribute opportunity, income, and meaning when traditional employment shrinks. Greater flexibility, including part-time work, could become an essential adaptation rather than a luxury. Implementing policies that push uniformly towards longer hours risk colliding with the very technological forces that are likely to reshape the economy.

Aging populations undeniably strain welfare systems, yet solutions exist beyond extending individual work time: earlier investment participation, smarter immigration focused on skills, and productivity-enhancing innovation. The deeper policy question isn’t whether people can work more, but whether that is the most intelligent lever available to focus on in the first place.

And this brings us to the deeper question beneath the policy debate.

Time, community, and wellbeing remind us that prosperity is more than hours worked. Photo by Platforma za Društveni centar Čakovec on Unsplash.

Holding Two Truths at Once

Like many advanced economies, Germany should strive to sustain economic vitality while preserving human dignity. A functioning welfare state requires participation and productivity, but at the same time a meaningful life requires autonomy, health, and time beyond labor. Any serious conversation needs to acknowledge both truths simultaneously.

The order of solutions therefore matters. Before choosing to restrict freedoms and rights, societies should first exhaust measures that improve incentives and conditions: fairer or more competitive taxation of additional work, promotion of a stronger investment culture, and innovation-driven growth. Focusing on these approaches can strengthen the economy without redefining personal balance as some kind of moral failure (as Merz did).

Ultimately, the debate is philosophical as much as economic. An economy is not an end in itself, but a tool to enable human flourishing. When policy begins to ask citizens to live primarily for output, it risks forgetting why prosperity matters in the first place. The real challenge is not deciding whether we should work more or less, but ensuring that whatever work we do ultimately serves a life worth living.

If you enjoyed this article, here are some next steps:

👉 If the goal is freedom, not just higher income: use my Financial Independence Calculator to estimate how many years of work you actually need, and what working 80% does to your early retirement timeline.

👉 Curious how Germany’s Early-Start Pension could reshape long-term wealth?

👉 Subscribe to The Good Life Journey (free tools & monthly newsletter, unsubscribe anytime)

💬 Do you think societies should solve labor shortages by changing incentives—or by asking people to work more? What would feel fair to you?

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing—with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens.

Disclaimer: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

Check out other recent articles

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Yes. Merz has repeatedly argued Germany must “work more” and criticized the idea that prosperity can be sustained with “four-day week” thinking and “work-life balance.” The current debate escalated because the CDU’s business wing is pushing policy language that targets “lifestyle” part-time work.

-

It’s a political label used to describe part-time work chosen for personal preference rather than caregiving, parenting, or training. Critics argue the term is vague and moralizing, because it treats legitimate life choices as socially suspect instead of neutral.

-

A proposal from the CDU’s business wing argues employees should no longer have a broad entitlement to reduce hours and that people should need “permission” unless they fit exemptions. Germany’s existing framework allows employees to request part-time after qualifying tenure and firm size, with limited refusal grounds.

-

Reported exemptions include people raising children, caring for relatives, or pursuing professional development/training. The controversy is that everyone else could be excluded—creating a system where private life must be “approved” to justify fewer hours.

-

According to reporting, Connemann said: “Those who can work more should work more,” describing the push to end “lifestyle part-time” as a response to skilled-labor shortages.

-

OECD analysis highlights shortages where demand exceeds supply particularly in areas including renewable energy/heating, nursing/healthcare, civil engineering/construction, hospitality, and transport.

-

It’s more nuanced. For example, one analysis notes Germany has low annual hours per worker but relatively high employment participation, meaning the issue may be the distribution of hours (part-time) more than unwillingness to work. “Lazy” is usually a values claim, not an economic diagnosis.

-

More hours tend to raise total output, not output per hour. Productivity growth typically comes from technology, skills, process improvement, and capital investment. Pushing hours without improving conditions can also raise burnout and reduce effectiveness over time.

-

Yes—official statistics have found millions working beyond contracted hours in recent years. This complicates the “idleness” narrative because the labor problem can be “who works too much and who can’t increase hours,” not simply “people refuse to work.

-

Common alternatives include improving incentives (tax and benefit design), expanding skilled immigration and credential recognition, increasing job mobility, and investing in productivity and working conditions. Several analyses also argue that disengagement and job quality matter: people don’t “opt out” randomly—they respond to incentives and meaning.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>