The 5 Psychological Barriers on the Road to FI — and How to Overcome Them

Each stage of FI—discovery, commitment, momentum, boring middle, and near FI—presents distinct psychological challenges we need to address. Photo by Racim Amr on Unsplash.

Reading time: 7 minutes

TL;DR — The 5 Psychological Barriers to Financial Independence

🤨 Stage 1 — Discovery: FI feels unrealistic or restrictive—future-self is abstract.

📚 Stage 2 — Commitment: Overwhelm and jargon stall progress—habits matter more than knowledge.

🚀 Stage 3 — Momentum: Savings accelerate—avoid extremism + lifestyle inflation.

⏳ Stage 4 — Boring Middle: Progress feels slow—trust autopilot, grow life beyond money.

🏁 Stage 5 — Near FI: One-more-year syndrome kicks in—define enough, retire to something.

Why Most People Don’t Reach FI — It’s Psychological, Not Mathematical

Do you really want to retire in your mid 40s? The journey towards Financial Independence isn’t just about spreadsheets and straightforward financial math, but often more about rewiring pre-existing narratives and deep-held beliefs, habits, identity, and emotions. Like Morgan Housel famously explained, money is more emotional than rational.

In this guide, we’ll break down the five psychological stages of Financial Independence (FI)—Discovery, Early Commitment, Momentum, The Boring Middle, and FI Arrival. At each stage, people face emotional and cognitive barriers that derail progress: skepticism, overwhelm, burnout, boredom, and fear of freedom. We’ll explore what each barrier feels like, why it happens, and practical ways to overcome it using behavioral psychology, habit design, and my own lived experience on the path to FI.

This article not only highlights the challenges but also gives practical solutions to overcome them, no matter where you currently are on your journey. These psychological barriers—more than income or math—are what stop most people from pursuing and achieving Financial Independence.

Before we dive in, it helps to know which stage you’re in. A simple way to tell is to notice your dominant emotion related to FI. If you’re skeptical, you’re early-stage. If you feel overwhelmed on what to do next, you’re likely in Stage 2. If you’re optimizing everything enthusiastically, that’s Stage 3. If it feels slow or flat, you’re in the “boring middle” (Stage 4). And if you’re close to your FI number but hesitant to leap, that’s Stage 5.

The path to FI is not only about understanding the math, but about rewiring pre-existing narratives and deep-held beliefs, habits, identity, and emotions. Photo by Nikolay Loubet on Unsplash.

Stage 1 — The Discovery Phase: Skepticism & Psychological Barriers to FI

The first stage is usually the hardest one to overcome, and the reason why many dismiss FI even after understanding its concept.

When people first hear about Financial Independence (FI), one of the most common internal barriers is the story that living below your means somehow equals deprivation—that pursuing FI requires strongly sacrificing today in exchange for some uncertain happiness or outcome down the road.

In reality, psychology and economics 101 provides a different story, and it’s important to remember two concepts. First, the idea of diminishing marginal utility shows that beyond a certain point, each additional unit of consumption adds less “happiness” than the one before it.

You can visualize this mentally as a graph whereby the outcome “happiness or satisfaction” increases strongly at first as we increase our consumption of goods and services. But once the basics are met, the curve tends to flatten little by little, until we get to a point where there is very little added value to each unit of increased consumption.

Second, the concept of hedonic adaptation illustrates how humans tend to return to a baseline level happiness even after income increases or lifestyle upgrades. You’ve probably experienced this yourself—you feel ecstatic when you get the raise or when you move into the nicer flat, but after a few weeks or months, the feeling fades away entirely. You adapt to your new situation and simply return to a pre-existing level of satisfaction.

Most US households are overflowing with gadgets, clothes, subscriptions, forgotten toys—not because they bring value, but because consumption has become somewhat automatic. We go throughout the year accumulating more and more stuff. Pursuing Financial Independence—especially the Lean FIRE version of it—challenges this default mindset and invites us to ask instead what really makes us happy. For most, that’s meaning, connection, and time.

Humans make financial decisions emotionally first, rationally later. Those emotions are often rooted in money scripts—unconscious beliefs formed in childhood, shaped by how our parents earned, spent, and argued about money.

Someone who grew up in a poor household often spends very freely as an adult—not out of irresponsibility, but as an unconscious self-reassurance. I know several parents who grew up in this situation and now enjoy a stable income and comfortable lifestyle, but show little focus on saving because of the underlying narrative “finally, we get to enjoy”.

The point here isn’t to blame, but to increase our awareness and to reflect on how did your own parents or grandparents deal with money, savings, and spending. It’s very likely you’ve inherited their own emotional attachments to money or reacting strongly to them in the opposite direction. The thing is that, once we see the script, it’s much easier to rewrite it.

Behavioral economics provides a clear explanation for why saving for FI feels less urgent. Humans tend to discount the future—a concept called hyperbolic discounting. We value immediate gratification more than long-term reward, and it’s the reason why people know they should save more but somehow never get around to it—there’s always a good reason to postpone saving.

Research from UCLA’s Hal Hershfield shows people neurologically perceive their future selves as strangers. So it makes sense for it being hard to save for “future you”—the brain barely recognizes them as you. This also aligns with Daniel Kahneman’s famous work in Thinking, Fast and Slow on System 1 instinct vs System 2 planning. The goal here isn’t to fight our natural wiring, but to make our future self feel more vivid, familiar, and real.

The solution is usually not willpower, but better design. Automate savings at the start of the month (a pay-yourself-first budget), so you lock in your desired savings rate and are allowed to spend what is left. Create visual trackers of progress towards FI—like using our FI Timeline Calculator—so the future can feel more tangible.

Another powerful reframing is to remind yourself that money doesn’t only buy things, it also buys options, time, and freedom. For me personally, it used to help to visualize that the part of my paycheck I was saving was really a small purchase of time and freedom. I was also consuming, just something I cared for more than material goods or status.

When the future becomes emotionally vivid rather than something abstract, saving can become energizing rather than some form of restriction.

Money doesn’t just buy goods and services, it also buys time-freedom. Photo by Lukas Seitz on Unsplash.

Stage 2 — Early Commitment: The Overwhelm Phase & How to Push Through

Once people are emotionally onboard with FI, overwhelm often hits next. There is a lot of financial jargon, opinions, Reddit wars on differing philosophies, and generally the fear of doing it wrong. This stage is where many people quit—it’s one of the most common challenges stopping people from starting FI. It’s paralysis by analysis.

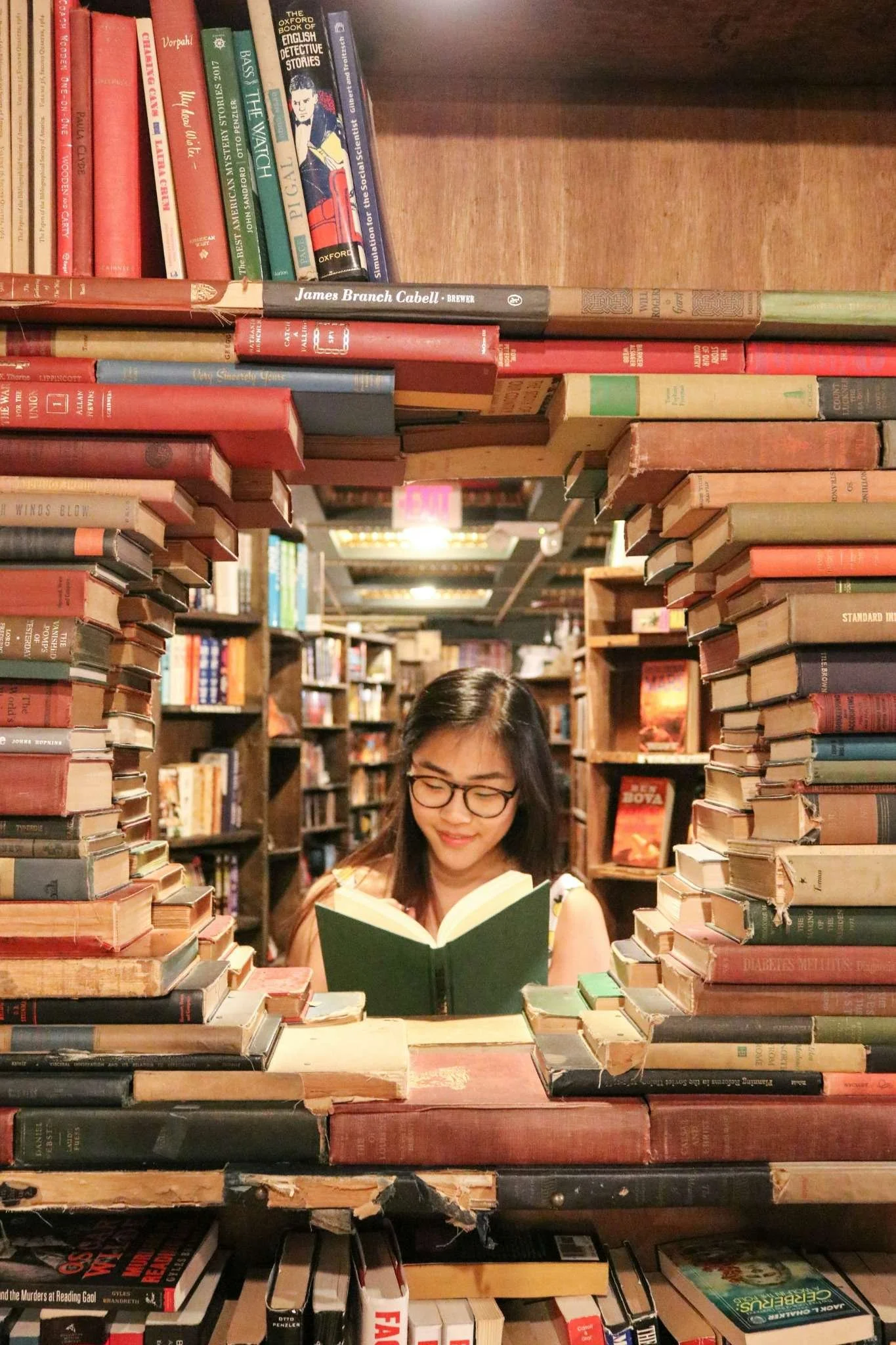

The solution is not to learn everything in one go, but allow yourself to learn one thing at a time. This is ultimately a marathon, not a sprint, and it takes time to internalize important concepts. Start out with learning about and setting up an emergency fund; learn about passive investing and the importance of low-cost, internationally-diversified index funds; and automate investment contributions at the beginning of the month.

Read one foundational book at a time—deep reading helps internalize the concepts far more than scattered advice in the internet. Focus on mastering one domino at a time, then the next. FI knowledge is layered, not necessarily linear, and you don’t need professional investor expertize to succeed. You only need patience, consistency, and discipline.

Early on the FI journey, many people aren’t actually resisting the saving itself, they’re sometimes just unclear on what building wealth actually means. A nicer car, a bigger house, or an upgraded phone are often unconsciously treated of status signals, the ultimate goal. But as Housel writes in The Psychology of Money, the greatest thing money can buy is control over your time—the freedom to wake up and decide how to live your day.

True wealth isn’t consumption, but autonomy. When people grasp this, their motivation flips. Saving no longer becomes a restriction, but a source of power and sovereignty. And that’s far more compelling than a slightly fancier car seat.

It’s also important to remember that FI doesn’t happen in isolation. Conflict often emerges when one partner is driven and the other isn’t, or when friends expect dinners, trips, and lifestyle norms that no longer align. The goal here isn’t about total conversion but about gradual realignment. Have open conversations with your spouse about values, not budgets. Many couples succeed with guilt-free spending allowances, or by gradually shifting their spending (e.g., the 1% savings rate method) instead of going cold turkey.

With friends, the goal isn’t withdrawal, but creativity. Invite people over to your home, build community frugally, and try to replace consumption with experience. In the end, all that friends really want is time spent together—it doesn’t have to be expensive.

If Stage 2 is about learning, Stage 3 is about acceleration—and sometimes the risk of going too far.

Stage 3 — Momentum: High Motivation, Optimization… and Burnout Risk

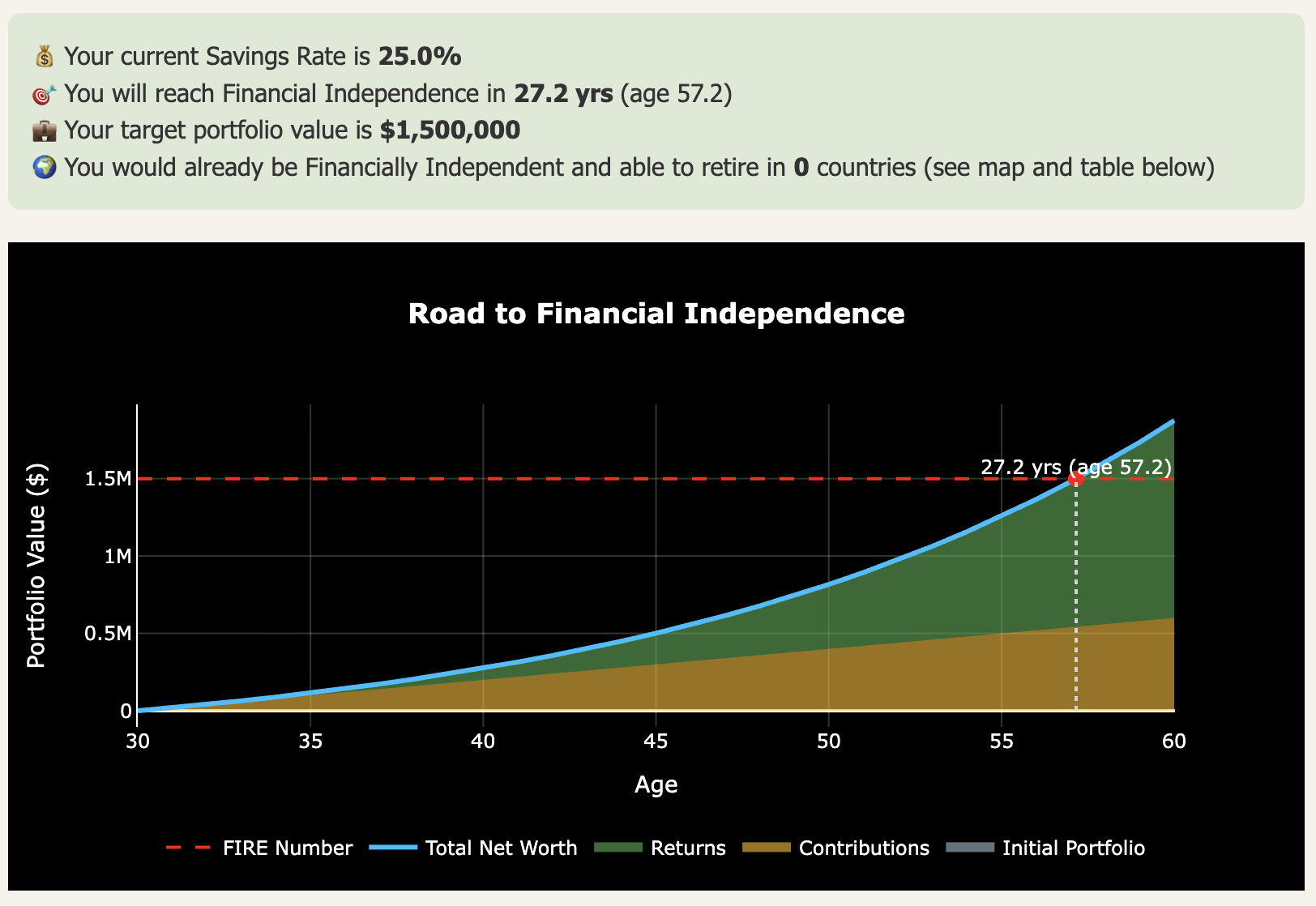

This phase is the most exciting one—it can feel intoxicating for many. Savings rate climbs—in some cases soars—net-worth graphs curve upwards, and the FI date on your calculator drops (see Figure 1 below). It’s thrilling to see the progress, how little, permanent changes in your lifestyle directly translate to buying you more freedom.

And that excitement often fuels the initial 2-3 years of the journey. You start to question many expenses you’d taken for granted for many years and that you assumed were fixed—subscriptions, convenience purchases, habitual dining out. People in this phase question whether each expense is truly aligned with an increase in joy or whether it’s just an automatic consumption.

So, they start choosing more meaningful spending over consumption. This stage is where you set the foundation to dramatically accelerate your FI timeline by reducing waste rather than joy. As the progress compounds, so does the motivation. Stage 3 is a wonderful place to be—so be sure to ride the wave.

Sometimes this momentum can turn into extremism. Some people go too far and cut out everything—travel, social life, generosity—and run on austerity. While this can be a reasonable short-term experiment that helps you identify what you’d really miss—what really brings value to your life—I wouldn’t recommend going down this route permanently.

There is a minimum frugalism threshold, below which savings continues to rise but happiness or satisfaction collapses. The goal of the FI journey should not be to set a decade-long path of joyless depravation, but about designing a sustainable lifestyle that’s aligned with your personal values and lifestyle preferences.

It’s true that younger readers can thrive on this temporary minimalist sprint—stripping their life back to the essentials to learn what truly matters to them, and then slowly and consciously reintroduce those luxuries. However, older readers or households with families may prefer a more gradual approach like the 1% incremental method: the goal here is to increase your savings rate by just 1% each month. This allows you to eventually arrive at a solid FI timeline without making crazy lifestyle adjustments from one day to the next.

A common trap in this phase to be aware of is lifestyle creep and lifestyle inflation. Raises and promotions arrive, and expenses are inched up in parallel. The problem is that now your expenses and FI number have ballooned, and your financial independence timeline drifts further away. The cure is often awareness and structure: remember to lock in salary increases by directing them to investments. Celebrate promotions and raises with one-time trips or experiences, rather than locking yourself into a permanent lifestyle up-grade.

But the high-motivation of Stage 3 doesn’t last forever—eventually the graph flattens, and the journey becomes internal instead of just numerical.

Figure 1: Screenshot of our Financial Independence Calculator—free for email subscribers. Figure out how early you could retire based on your current trajectory and how small changes in your savings rate could bring early retirement closer.

Stage 4 — The FI Boring Middle: Plateau, Patience & Reinventing Purpose

Stage 4—often called “the boring middle”—is where I personally find myself on after 7-8 years pursuing FI. This stage is certainly less exciting in the financial sense, but with the right framing it can be just as exciting in many other areas.

Once everything has been fully optimized and you have a clear handle on things, the financial journey simply becomes less eventful. There is nothing left to do—you’ve reached a lifestyle you’re comfortable with, your savings are fully automated, you’ve read all the books, and your portfolio is simply compounding quietly in the background.

During the boring middle progress continues to be real, but just feels slower, certainly invisible week-to-week. Without any novelty, sometimes impatience can creep in, and people can find themselves chasing shortcuts, timing the market, stock-picking, or questioning the whole path altogether.

This boredom often collides with market volatility, making it tempting to “do something”—pick stocks, time entries and exits, chase alternative assets. It feels productive to do something rather than nothing, but this almost always backfires. This is the phase where discipline matters more than intelligence.

The solution is to zoom out. You probably no longer require the diligent tracking you implemented during the first stages. Your habits are already well-established, and tracking your progress too often is doing much more harm than good. Why not take a step back and reduce how frequently you track your expenses and investment accounts? It’s really enough to track accounts quarterly—not monthly, and certainly not daily. Trust the systems you’ve built, and let compounding work for you.

During this stage, it’s not uncommon for people to feel very drained from a stressful job or career they don’t enjoy. The road to reaching FI seems far away and they begin to question whether they will survive another 5-8 years in their working situation. This certainly happened to me—I began to experience burnout at work, and was unsure how to proceed.

The good news is that being already many years into the FI journey grants you the ability to decide from a position of strength. Many FI folks decide to plough through until the end—this is usually the better decision from a purely financial perspective. But it does carry costs, often related to health. Workers in demanding careers often have little time to focus on their mental and physical wellbeing—the workplace can really take a lot of energy out of them.

Others—including myself—may see this stage as an opportunity to switch gears, change careers, or at least work part-time. Especially if you envision continuing to work after reaching FI, rather than enduring 6 more years of misery and poor health, why not begin already to construct what your post-FI life and identity will look like?

Even if you do decide to stay on the same job until the end, it’s important to look at identity diversification to not have a life crisis when you eventually do reach FI and leave your job. Overall, FI shouldn’t be an escape plan, but a space for redesigning what you want your life to look like.

Personally, Stage 4 shifted my focus. I stopped optimizing or micromanaging finances because the system was already well greased—investments were automated and expenses and savings fairly predictable. Instead, I shifted the focus towards something equally—if not more—important than financial health: health itself.

What’s the use of Financial Independence if you lose your health in the process? Recently, I’ve shifted my attention to learn more about healthspan, longevity, sleep, diet, training, and energy levels. It felt natural that once the financial system runs in autopilot that I should redirect my energy towards optimizing for physical and mental wellbeing.

Much of The Good Life Journey blog has also gradually shifted that way too—not by accident, but because FI became less of a destination and more of a foundation, of an enabler. I’m still very interested in the financial part—and in helping others get there. But, we should also ask the deeper philosophical questions in life—what is this financial freedom for?

And then there’s my family. I’m in the “boring middle” financially, yet I have three little ones at home—two of them toddlers. So, rest assured there’s nothing boring about my life at the moment. It’s chaotic and exhausting, but also beautiful and full of special moments. If I spend these years staring at a net worth trackers instead of Lego blocks, I know my future self will look back in regret.

I try to remind myself often that the numbers are under control—now we just need to be present and enjoy the journey. One day, I’ll likely look back on this period as the richest one of all, of course, not related to financial growth but life growth. If you have a family, lean into it. If you’re single, pour your energy into friendships, passions, and adventures. What memories would you like your 90-year-old self to replay with a smile?

To prevent stagnation during the boring middle, it helps to consciously introduce more joy and curiosity into your life. This is a great phase to design and test parts of your post-FI identity, rather than waiting until you reach the number. What hobbies are you cultivating? What kind of days do you want to wake up to? Who do you want to spend time with in early retirement?

Start experimenting now—try taking a short mini-retirement, explore creative or entrepreneurial projects, try slow-travel for a month, pick up a skill you’d always wanted to learn but had been postponing. Since most of us have build a strong enough financial foundation by stage 4, we can also afford to loosen the purse strings strategically—not to fall back into mindless consumption, but to invest in memorable experiences, relationships, and meaning.

For me, this is where the journey becomes less about cutting costs and more about actively designing what you want your rich life to look like. You’re not just buying freedom in the future, you’re practicing how to live it today.

Surprisingly, the final stretch is often the hardest—not financially, but emotionally.

At stage 4, i.e., “the boring middle”, your system is in place and it’s just a waiting game. This is the perfect chance to turn your attention to improve other important dimensions like your health or relationships.

Stage 5 — Nearing Financial Independence: OMY Syndrome & Freedom Anxiety

Stage 5 comes when the finish line starts to appear in the horizon. Many expect this phase to feel euphoric—but psychological resistance often spikes instead. Surprisingly, fear often replaces excitement and people fall into the one-more-year (OMY) syndrome: they decide to add “just one more year of work” again and again. They prefer to have a larger buffer, then a larger one still. We’ve written about the OMY syndrome where work and income is familiar, and freedom uncertain.

The solution here isn’t force, but clarity. It’s important to define what enough looks like for you, and to prepare during Stage 4 for how you will navigate any potential identity crisis. You need to be retiring to something, not away from something. Sure, you can’t wait to leave your job, but if you haven’t prepared extensively for what comes next you may be in deep trouble. As mentioned, taking mini-retirements can be a great practice runway, because it forces yourself to already think about how you will use your time on a day-by-day basis.

Even if we disliked them, jobs gave rhythm, social structure, status, and a sense of belonging. Removing them creates substantial space—which will feel empty if you haven’t build identities elsewhere. The antidote is to build identities outside your career early on in the form of hobbies, community, creativity, health, and contribution.

During stages 1-4 freedom sounds ecstatic… until it finally arrives. Without structure and things to do, days can become a blur—not different from traditional 65-year-old retirees who don’t know what to do with themselves. Without purpose, free time weighs heavy. Live pieces of FI now while you’re still in stage 4—in the form of sabbaticals, part-time work, and slow mornings.

Build the life you want before you need it—FI shouldn’t be the end, but the opening chapter of something rich and memorable.

Beneath all the numbers, the most useful question is simply: Which stage am I in right now? Most people don’t get stuck on their path to FI because the math is wrong—they get stuck because the psychology of their stage is unaddressed. Once you recognize the stage, the next step to take becomes obvious.

💬 Which stage of the FI journey are you currently in—and what belief, habit, or fear is/was holding you back and how are you dealing with it?

👉 New to Financial Independence? Check out our Start Here guide—the best place to begin your FI journey.

👉 Want to understand how to reach Financial Independence in your mid-40s? Check out what savings rate will get you there depending on age and current portfolio size.

👉 Looking to retire a decade or more early? Use our Financial Independence Calculator (free for email subscribers) to plug in your numbers and see how soon you could go into retirement.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Disclaimers: I’m not a financial adviser, and this is not financial advice. The posts on this website are for informational purposes only; please consult a qualified adviser for personalized advice.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

The most common barriers include skepticism (FI sounds unrealistic), overwhelm during early learning, burnout during aggressive saving, boredom in the “middle years,” and fear when the finish line approaches. These stages often stop people long before math does.

-

Because money decisions are emotional, not rational. Hedonic adaptation, future-self discounting, status spending and lifestyle creep erode savings. Without awareness and systems, income alone doesn’t lead to independence.

-

It’s the stage after optimization where progress is slow and invisible. Systems are set, investments compound quietly, and motivation fades. The solution: zoom out, reduce tracking frequency, and build identity and joy outside of net-worth growth.

-

Shift focus toward life design — hobbies, health, family, creativity, community. Experiment with mini-retirements, slow travel, or part-time work. Presence, not spreadsheets, becomes the real work.

-

“One-More-Year Syndrome” occurs near FI when fear replaces excitement. People keep working for safety buffers instead of transitioning to freedom. The antidote is defining enough and practicing retirement before reaching it.

-

Childhood experiences shape spending instincts unconsciously — scarcity can lead to overspending, abundance to avoidance. Awareness allows script rewiring.

-

Hyperbolic discounting makes future rewards feel distant. Automating savings and visualizing future freedom shift motivation.

-

Yes — Stage 4 is proof. FI isn’t about deprivation but alignment. With kids, presence may be the highest-return investment.

-

Talk values, not budgets. Use guilt-free spending allowances and gradual savings increases to avoid friction.

-

Notice your dominant emotion: disbelief, overwhelm, motivation, plateau, or hesitation. Your stage determines your next step — not your net worth.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,127,103);

});

</script>