How to Stay Hopeful in an Age of Bad News and Doomerism

It’s easy to succumb to doom and despair when facing global issues like climate change. This article teaches you a simple mental model to help you face global challenges with a hopeful and realistic mindset. Photo by Raychel Sanner on Unsplash.

Reading time: 9 minutes

Author’s note: I worked in climate science and sustainability for over a decade, and I’ve seen firsthand how constant exposure to negative global trends affects mental health—both mine and my colleagues.

What this article covers:

• Why the world feels overwhelming

• How to cope with bad news and doomerism

• A mindset to reduce climate dread and anxiety

• Evidence-based signs of progress

• A practical framework for emotional resilience

TL;DR — How to Stay Hopeful in an Age of Bad News

🌪️ Why the world feels overwhelming: Our brains and news feeds focus on crises, creating an incomplete—and often depressing—story about the world.

🌱 What’s actually true: Human wellbeing has improved dramatically even as environmental pressures have risen. Both “awful” and “better than before” can be true at the same time.

⚡ Real hope for climate change: Clean energy is now cheaper, and data shows many countries are starting to decouple emissions from economic growth.

🧠 The mindset shift: Learning to hold multiple truths (“awful today; better than before; can be much better in the future”) helps reduce doomerism, climate dread, and anxiety about world events.

💪 How to apply it: Curate your information diet, zoom out to long-term trends, and adopt a balanced framework that keeps you grounded, resilient, and hopeful.

A More Sustainable Mindset for a Good Life: How to Stay Hopeful in Hard Times

It’s no wonder so many of us look a bit downcast at times. Every single day, our social media or news feeds offer us a stream of daily crises to consider. What are we worrying about today—climate collapse, ongoing wars, existential AI risks, or economic uncertainty?

Unsurprisingly, many people feel a rising sense of helplessness, even despair. Today I want to share what has helped me reverse this feeling. In this article, I’ll show you a practical framework, based on Hannah Ritchie’s work from OurWorldInData, to cope with the constant stream of bad news, reduce climate dread and doomerism, and build a more resilient mindset grounded in both reality and hope.

I worked in the fields of climate change and sustainability for over a decade, and I’ve seen firsthand how constant exposure to negative global news has affected the mental health of colleagues. I wish I would have stumbled upon the concept I’m presenting today much earlier.

Yes, information diet is a thing and certainly helps, but today we’re going a few steps beyond. On top of an information diet, I think we need a complete shift in perspective.

What if part of this emotional weight we feel comes not from the size of these global problems—which, objectively, are very big—but from the incomplete story we tell ourselves about the world? This incomplete story is what fuels doomerism and the sense that the world is getting worse, even when long-term trends show a more nuanced picture.

This article begins by examining closely the climate and environmental challenge—where this doomer narrative is understandably strong—and uses it to introduce a mindset that reduces despair, increases emotional resilience, and helps us see progress, danger, and opportunity with more clarity.

By the end of this article, I hope you’ll leave not only more hopeful in light of the multiple crises we face, but also with a simple mental model you can apply—not just to the climate problem, but to AI safety, war and geopolitics, or whatever worries you most.

As we’ll show below, falling renewable energy costs is enabling a decoupling between GHG emissions and GDP. Economies are growing and reducing their emissions—something almost unthinkable a couple decades ago. Photo by Jesse De Meulenaere on Unsplash.

The Sustainability Equation: Why the World Feels So Depressing—and What We Miss

In 1987, UN World Commission on Environment and Development defined sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”. Unfortunately, very often conversations about sustainability focus almost exclusively on the “future generations” half of the equation—protecting tomorrow’s world—while overlooking how difficult “meeting the needs of the present” used to be for those that came before us.

Historically, humanity failed spectacularly at meeting the needs of people alive at the time. When we forget this, it becomes easy to feel like the world today is uniquely depressing or unsustainable, even though past generations faced far harsher realities. This is one reason sustainability discussions so often leave people feeling hopeless rather than empowered.

Child mortality was incredibly high, lifespans were short, and, unlike today, most lives were defined by scarcity. If we apply the full UN definition of sustainability, humans have never really achieved true sustainability in the past. Not because we didn’t once live in more harmony with nature, but because we couldn’t provide the most basic forms of security for ourselves..

This context matters when we examine the prevailing narrative of everything going downhill in the modern era. It’s always been downhill—just that before it was because the most basic needs weren’t met, while today it’s because of our unprecedented impact on nature and ongoing release of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The two core conditions of sustainability have effectively flipped.

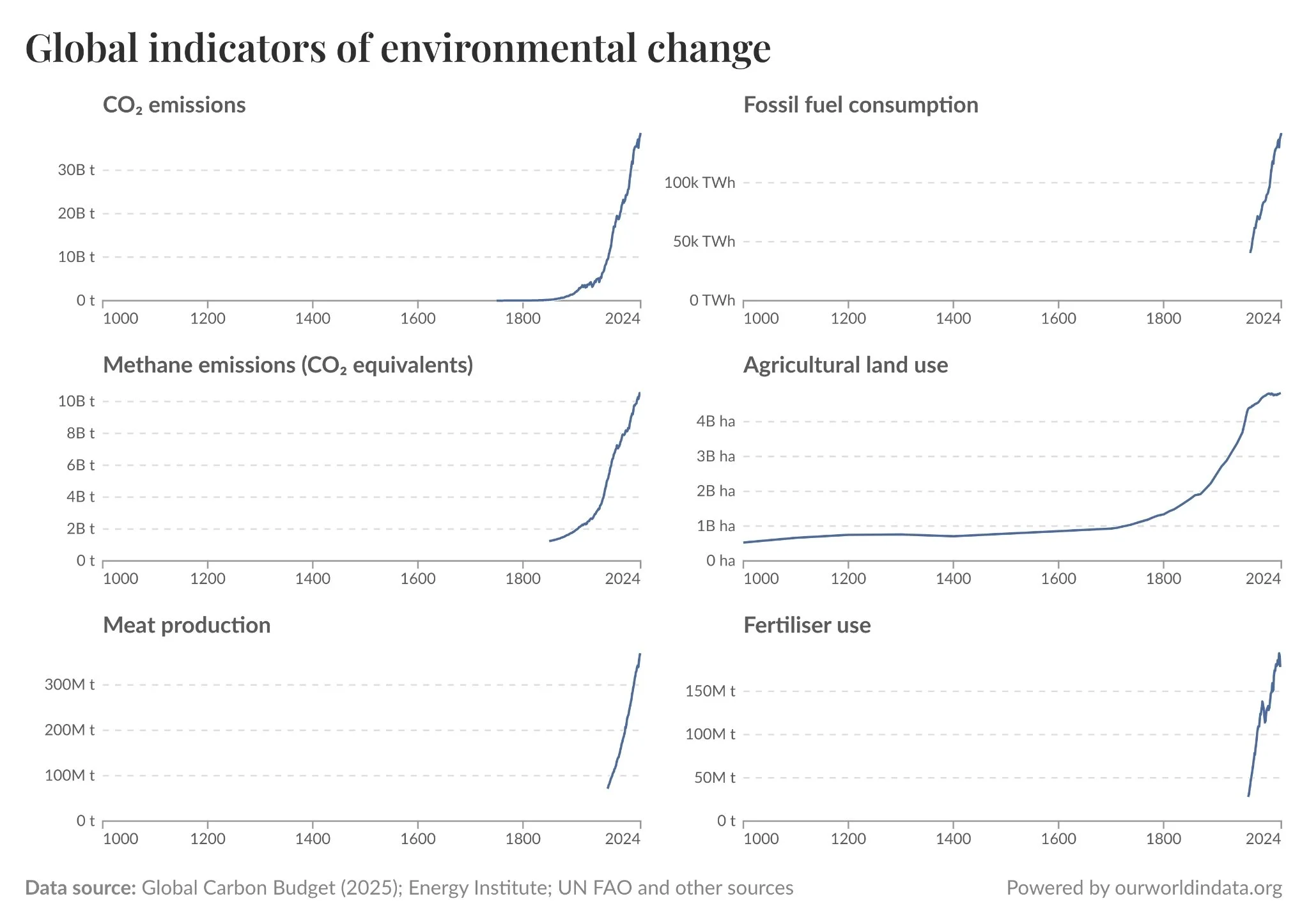

The doomsday narrative is reinforced by graphs like the ones shown in Figure 1, which usually begin in the 1950s or 1970s and paint a picture of stability followed by sudden crisis—pollution rising, GHG emissions rising, species decline accelerating, etc. Everyone working in the environmental/climate space—as I did for over a decade—is aware of these graphs. But, again, these visuals are only showing half of the story: the environmental half of the equation.

Figure 1: Global indicators of global change over the last decades. This half of the sustainability equation has clearly worsened over time. Source: multiple sources from OurWorldInData.

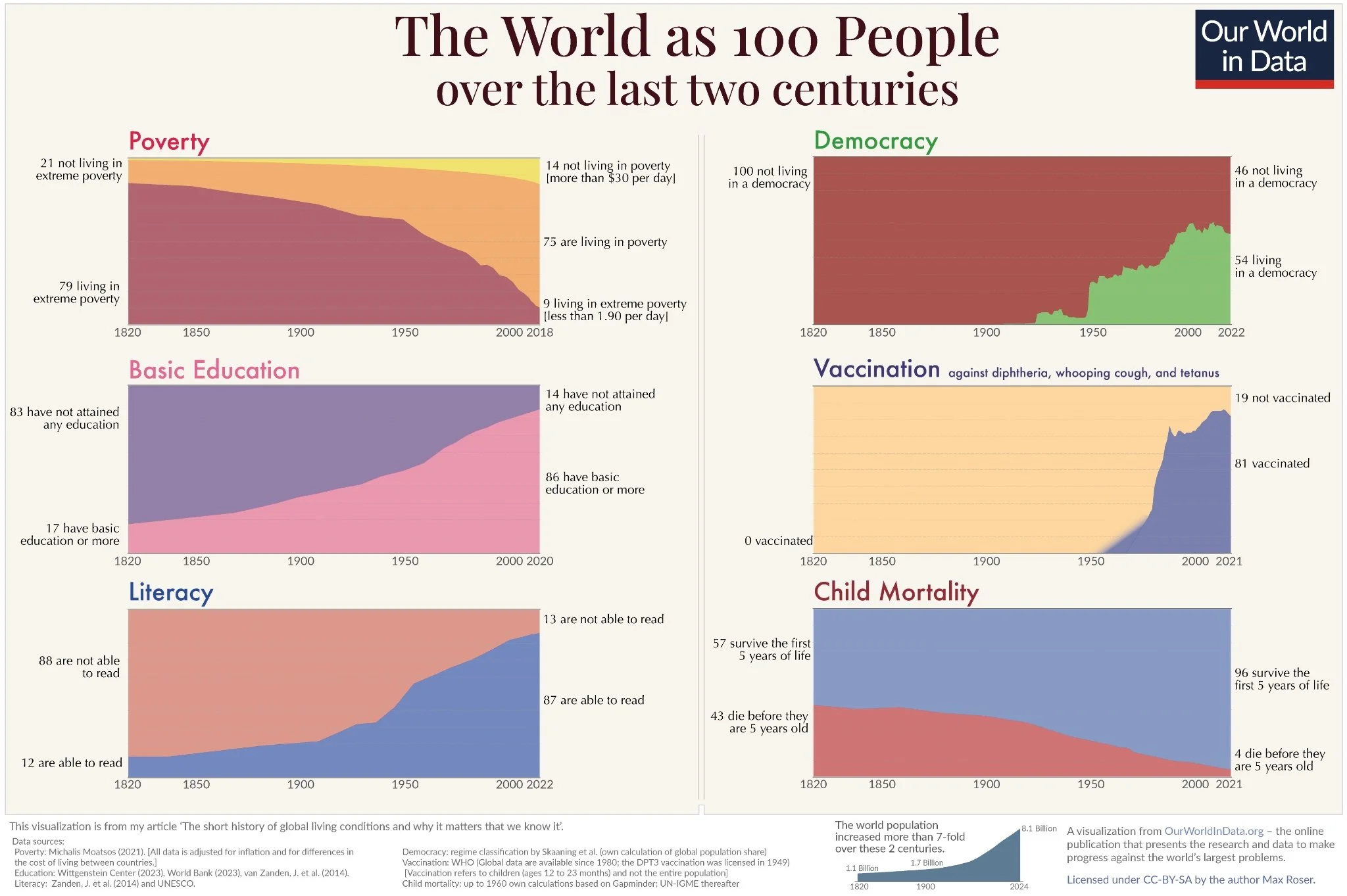

It’s omitting the simultaneous revolution in human wellbeing (Figure 2 below). Over the same decades, child mortality collapsed, lifespans increased dramatically, education soared, maternal mortality plummeted, and extreme poverty fell to historic lows. In other words, the environmental line curves upward, but so did the human progress line. To understand sustainability fully, both must be examined side by side.

What this breakdown reveals is that the story of sustainability isn’t “things used to be fine and recently we broke them”. We did improve human wellbeing dramatically—half of the sustainability equation—but did so at the cost of drawing down on the environmental capital of the planet.

The sustainability challenge, then, is not to go back to some imagined eco-utopia that never existed, but to achieve what no generation in history has managed before: material wellbeing for people today and a thriving, liveable planet for our kids and their successive generations. This framing alone already begins to loosen the doomer thinking—it shows we’re not actually falling from Eden, but trying to build something unprecedented.

This change in framing represents an important mindshift—it means we are the first generation that can actually solve the sustainability problem. There’s no time to feel guilty or to give in to despair—we have a challenge to solve.

Figure 2: The second half of the sustainability equation—human wellbeing and prosperity has soared over the last century. Source: OurWorldInData.

Why Progress and Environmental Decline Happened Together—and Why It Matters Today

As human health, prosperity, and longevity soared over the past two centuries, our energy use, resource consumption, and environmental impact increased in lockstep. This was not a coincidence, but the price we paid for improvement. Energy from fossil fuels powered sanitation systems, antibiotics production, safe drinking water, and an agriculture system that until recently was not thought could keep pace with a growing population.

This transformation drastically reduced preventable deaths. When we look at the historical data, the curve of human wellbeing and the curve of environmental impact move upwards together. Progress was real, and so were its costs. Younger generations today tend to forget the world we’re coming from, and without this perspective, the way modern society is structured can easily appear nonsensical.

But we can go even a step further and remember that humans haven’t become environmentally damaging since the industrial age alone. Archaeology and ecology show that early human societies drove multiple waves of extinctions across continents. Consider that all continents had their own version of dangerous creatures that Africa still has—we just wiped them out from these other regions.

When Homo sapiens arrived in Australia, North America, and many island ecosystems, megafauna rapidly disappeared—even though the planet’s total population was likely between 5 and 10 million. The extinction per capita was likely much larger then.

Long before factories and intensive agriculture, humans have altered landscapes, burned forests, hunted species to extinction, and transformed ecosystems. I’m certainly not excusing our current damage, but it does help dispel the myth that our pre-industrial past was a golden era of harmony with nature. Impact has always been a part of the human story.

So, while I think it’s fair to say that overall, our ancestors had a lower environmental impact than modern societies in absolute terms, it’s also fair to say they failed the other half of the sustainability equation—they lived short, fragile, sick, and dangerous lives. They weren’t more sustainable because they stewarded the environment better; they simply lacked the technological muscle to cause larger-scale harm.

In other words, the sustainability problem did not begin with modern humans—it simply went to the next level with modern humans, enabled by technology. Understanding this helps us avoid romanticizing the past and instead focus on what’s possible now from our abundance vantage point: using our same ingenuity that lifted billions out of suffering to also protect the environment that sustains us.

Here’s where the story takes an unexpected turn—a hopeful one.

Decoupling: Is There Still Hope for Climate Change? Yes—and Here’s Why

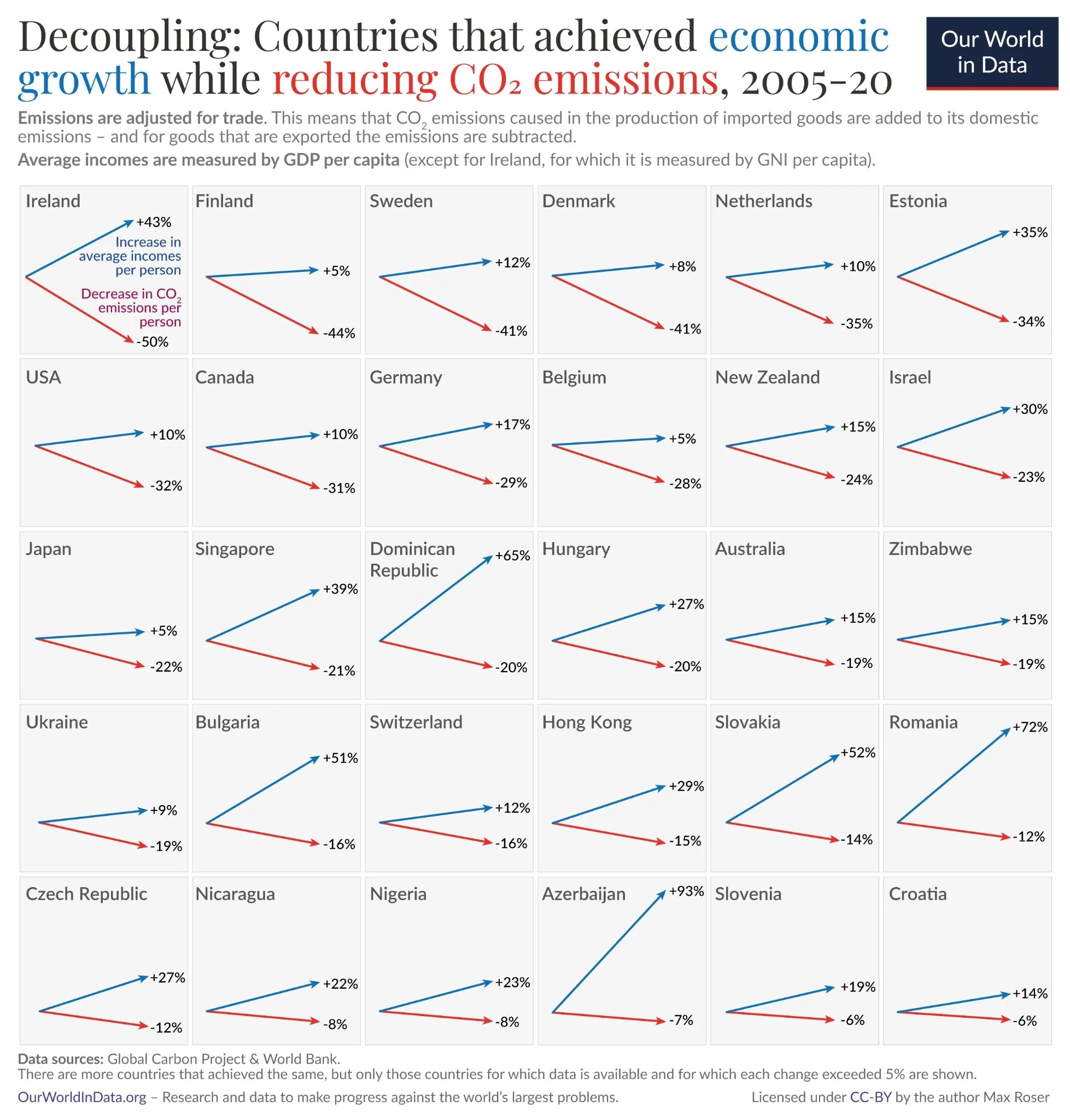

Despite the slow pace of decarbonizing our economy, for the first time in history we are beginning to see real examples of countries improving living standards while reducing GHG emissions. This idea—“decoupling” in technical lingo—is the centerpiece of Hannah Richtie’s optimism, and should be for the rest of us too. This decoupling is visually presented in Figure 3 below.

Renewable energy prices have fallen faster than almost anyone had predicted. Solar, wind, and batteries are now cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives in many regions. This matters for anyone asking whether there is still hope for climate change—falling clean energy costs are one of the strongest signals that progress is not only possible, but increasingly the path of least resistance.

Moreover, some nations are cutting CO₂ emissions despite economic growth, showing that environmental impact and prosperity no longer need to rise together. We are at the beginning of a technological shift that makes the full sustainability equation solvable for the very first time.

When we take this long view approach, it’s clear that humans are not just problem-creators, but problem solvers. The story of the past 150 years is a story of humanity repeatedly achieving extraordinary things that once seemed impossible: eliminating smallpox, reducing child deaths by more than half, raising global literacy, drastically cutting extreme poverty, and inventing tools—from antibiotics to clean water systems—that reshaped our life expectancy.

It’s this very same problem-solving capacity that is now being turned towards clean energy, decarbonization, biodiversity protection, and circular resource use.

Recognizing this bigger picture matters for our mental wellbeing. Trust me—colleagues in the climate and sustainability space are not jumping up and down when it comes to mental health. I remember times when colleagues felt drained by writing report after report about worsening trends, rarely pausing to acknowledge where progress had been made or the broader context that brought us here.

If we believe our problems are unprecedented or unsolvable, despair feels inevitable. But when we understand that humans have repeatedly transformed the world for the better, we are better able to reinterpret the moment we’re living in. Climate change demands urgency and action, yes—but not fatalism and despair.

Technological transitions are not instantaneous, and political will, economic power, and vested interests are uneven, but the forces of innovation and human ingenuity are generally pointed in the right direction. This is the first generation that has a realistic shot at achieving what previous ones could not: improving human wellbeing while reducing environmental pressure.

And that alone should give us a more grounded sense of hope.

Figure 3: Examples of countries having decoupled economic growth from CO₂ emissions.

How to Cope With Bad News and Doomerism Using the “Three Truths” Framework

For me, one of the most powerful ideas from Hannah Ritchie’s article is the ability to hold multiple truths at once: the world is awful, the world is better, and the world can be much better. As we saw above, these statements are not contradictions, but layers of reality.

Climate impacts are real and worsening, environmental degradation is very serious, and species are under threat. And yet, across many measures of human wellbeing, the world is dramatically better than it was even 50 years ago. Accepting both truths allows us to better understand reality without collapsing into despair. It trains us to perceive and understand complexity, not just crisis.

Sometimes what feels like cognitive dissonance is actually just reality being complex. Understanding this helps reduce climate dread and the sense that everything in the world is spiraling downward out of control. And the skill we need is not to force the world into a single, simple narrative, but to become more comfortable holding multiple truths at once.

This mindset becomes important in a media environment that is shaped by negativity bias. We are wired to notice threats, and news algorithms amplify negative stories because they hold better our attention. Unfortunately, when we consume a steady diet of daily crises, we lose sight of long-term trends and human progress. We are so absorbed into the day-to-day minutiae that we forget to study history.

Applying the “awful/better/can be better” framework helps us interrogate our reflexive emotional response to news headlines. It encourages us to ask: Is this the whole story? In what direction are the long-term trends moving? What solutions are emerging that I’m not seeing in the news feed? This mindset doesn’t numb us—it simply grounds us and reduces emotional overwhelm, while staying true to reality.

The good news is this simple framework applies far beyond climate change. In geopolitics, it helps us acknowledge the horrors of current conflicts while recognizing that global death rates per capita from war have declined over the past century. The risk of dying from war has generally declined relative to global population, and major inter-state wars—despite a recent uptick—are less common today than they were in the early and mid-20th century.

In AI, it reminds us that while safety concerns exist, we also have an unprecedented ability for global coordination and safety research—something no previous transformative technology enjoyed. There have also been improvements in the AI safety story. Before a public statement on “AI extinction risk” was signed in 2023 by leading CEOs and researchers, the issue received far less explicit attention

Simultaneously, things look bad today (not enough being done about AI safety), looked worse before in some fronts (the problem used to be even more ignored), and there is the potential for AI safety improving in the future if we get our act together.

In economics, the same “multiple truths” pattern shows up. Long-term living standards have risen dramatically—people today generally have better health, safety, education, and access to technology than any previous generation. Yet many young adults feel worse off, and not without reason: housing, education, and childcare costs have risen faster than wages in many wealthy countries, making perceived core milestones like home ownership feel out of reach.

At the same time, expectations for lifestyle, mobility, and financial security have grown faster than income, while social comparison—amplified by the internet and social media—makes it easy to feel like you’re falling behind. So, both realities are true: life is materially richer than ever, and for many, life also feels more economically stressful.

This mirrors the emotional tension many people feel when asking whether the world is getting worse—data shows long-term improvement, while lived experience shows real pressure. Recognizing this tension helps us see the bigger picture without dismissing the lived experience of younger generations.

Whether climate, geopolitics, war, AI, or economics, seeking out and holding multiple truths prevents us from surrendering our mental health or buying into simplified narratives that don’t exactly match reality. Instead, seeking to hold multiple truths keeps us focused on meaningful action and constructive hope.

This mindset is not too dissimilar to what some spiritual leaders like the Dalai Lama advocate for. Yes, there are ongoing tragedies in the world, but he highlights there are also far more individual examples of good and kindness taking place all around us. Accepting this reframed mindset doesn’t need to draw us towards inaction—the Dalai Lama has been politically active his entire life—but helps us cultivate mental resilience.

Solving climate change, global conflicts, AI challenges, or economic issues is rarely a sprint—and we need mentally-resilient citizens out there working on these marathons, not workers quiet-quitting and bordering on depression.

Worried about or working on a challenging global problem? Feeling depressed about it or quiet quitting never helped advance anything. Photo by Brooke Cagle on Unsplash.

How to Stop Feeling Hopeless About the State of the World

Adopting this balanced worldview—acknowledging danger, progress and possibility simultaneously—is not just useful for interpreting global problems; it’s a deeply practical tool for emotional resilience. When we learn to hold multiple truths, we become less reactive to alarming headlines, less susceptible to nihilism, and more capable of responding thoughtfully rather than fearfully.

It allows us to stay engaged without burning out, to care deeply without collapsing under the weight of the world. In this sense, emotional sustainability becomes just as essential as environmental sustainability.

For those pursuing a good life, this perspective matters enormously. A life lived under the perception of constant threat—whether the threat of climate collapse, economic instability, or technological danger—is a life constrained by fear. But when we intentionally zoom out to include the full arc of human progress, we find something surprising: hope that is rooted in evidence.

Humanity has overcome extraordinary challenges before, and we will do so again. Seeing this clearly doesn’t excuse inaction, but empowers it. We act more constructively from a place of grounded optimism than from a place of despair.

On a practical level, adopting this mindset does mean curating your information diet, seeking out long-term trends rather than daily noise, and reminding yourself regularly that progress and peril coexist. It’s one of the most effective ways to cope with bad news, avoid doomerism, and stay grounded during overwhelming world events. It means practicing gratitude not just for personal blessings but for civilizational-level ones too: clear water, medical care, declining poverty, or renewable energy breakthroughs.

Above all, it means choosing hope as a habit—not naive hope, but informed hope, the kind rooted in data, history, and the extraordinary human capacity for solving problems. This perspective doesn’t guarantee a perfect future, but it does make it far more possible to take positive action in the world. It also makes life richer, steadier, and more joyful along the way.

💬 What do you think of this 3-piece framework? What do you care about dearly and how could you implement it in your life? Please share with us in the comments section further below.

🌿 Thanks for reading The Good Life Journey. I share weekly insights on personal finance, financial independence (FIRE), and long-term investing — with work, health, and philosophy explored through the FI lens. If this resonates, join readers from over 100 countries and subscribe to access the free FI tools and newsletter.

Today’s article was largely inspired by Hannah Ritchie, a scientist from OurWorldInData. If you want a more data examples of this concept I recommend reading her article.

About the author:

Written by David, a former academic scientist with a PhD and over a decade of experience in data analysis, modeling, and market-based financial systems, including work related to carbon markets. I apply a research-driven, evidence-based approach to personal finance and FIRE, focusing on long-term investing, retirement planning, and financial decision-making under uncertainty.

This site documents my own journey toward financial independence, with related topics like work, health, and philosophy explored through a financial independence lens, as they influence saving, investing, and retirement planning decisions.

Check out other recent articles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

-

Because we’re exposed to more negative information than any generation before us. News algorithms prioritize crises, which makes the world seem worse than long-term data shows. Understanding this gap helps reduce overwhelm and gives a more realistic picture.

-

Both. Some trends—like climate impacts—are worsening, while human wellbeing, health, education, and poverty have improved dramatically over decades. Holding both truths helps us avoid doomerism and respond constructively.

-

Create an intentional information diet, limit doomscrolling, and zoom out to long-term trends. Pair awareness of risks with recognition of progress. This balanced mindset reduces anxiety and keeps you engaged without burning out.

-

Doomerism often comes from seeing only one part of reality. Expand your perspective to include human progress, emerging solutions, and areas where things are genuinely improving. This reduces hopelessness and restores agency.

-

Climate dread comes partly from feeling powerless. Learn about decoupling, falling renewable prices, and real progress being made. Pair this with meaningful personal or civic action to rebuild a sense of control.

-

Yes. Clean energy is rapidly becoming cheaper, countries are beginning to decouple emissions from growth, and many solutions are scaling. The challenge is serious, but despair is not warranted—progress is real and accelerating.

-

Humans are wired for negativity bias, and modern media amplifies it. This can make problems feel bigger than they are. Balancing awareness of risks with evidence of progress helps restore emotional stability.

-

Shift from reactive consumption of news to intentional, limited exposure. Practice holding multiple truths: things can be dangerous and improving at the same time. This mindset reduces fear while keeping you informed.

-

Human activity has undeniably caused environmental harm, but humans also have the capacity to solve problems at scale. The same ingenuity that created challenges is now driving solutions like clean energy and conservation.

-

Historically, we lacked the technology to meet human needs without harming nature. Today, for the first time, decoupling offers a path to both human wellbeing and environmental sustainability. It’s difficult—but possible.

Join readers from more than 100 countries, subscribe below!

Didn't Find What You Were After? Try Searching Here For Other Topics Or Articles:

<script>

ezstandalone.cmd.push(function() {

ezstandalone.showAds(102,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,119,120,122,124,125,126,103);

});

</script>